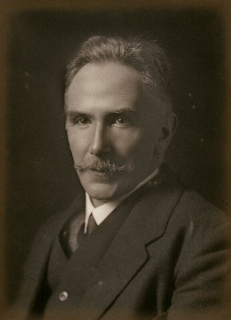

John Tyndall, Irish experimental physicist who, during his long residence in England, is an avid promoter of science in the Victorian era, is born on August 2, 1820, in Leighlinbridge, County Carlow.

Tyndall is born into a poor Protestant Irish family. After a thorough basic education, he works as a surveyor in Ireland and England from 1839 to 1847. When his ambitions turn from engineering to science, he spends his savings on gaining a Ph.D. from the University of Marburg in Marburg, Hesse, Germany (1848–1850), but then struggles to find employment.

In 1853 Tyndall is appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy at the Royal Institution, London. There he becomes a friend of the much-admired physicist and chemist Michael Faraday, entertains and instructs fashionable audiences with brilliant lecture demonstrations rivaling the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley in his popular reputation and pursuing his research.

An outstanding experimenter, particularly in atmospheric physics, Tyndall examines the transmission of both radiant heat and light through various gases and vapours. He discovers that water vapor and carbon dioxide absorb much more radiant heat than the gases of the atmosphere and argues the consequent importance of those gases in moderating Earth’s climate, that is, in the natural greenhouse effect. He also studies the diffusion of light by large molecules and dust, known as the Tyndall effect, and he performs experiments demonstrating that the sky’s blue color results from the scattering of the Sun’s rays by molecules in the atmosphere.

Tyndall is passionate and sensitive, quick to feel personal slights and to defend underdogs. Physically tough, he is a daring mountaineer. His greatest fame comes from his activities as an advocate and interpreter of science. In collaboration with his scientific friends in the small, private X Club, he urges greater recognition of both the intellectual authority and practical benefits of science.

Tyndall is accused of materialism and atheism after his presidential address at the 1874 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, when he claims that cosmological theory belongs to science rather than theology and that matter has the power within itself to produce life. In the ensuing notoriety over this “Belfast Address,” his allusions to the limitations of science and to mysteries beyond human understanding are overlooked. He engages in a number of other controversies such as spontaneous generation, the efficacy of prayer and Home Rule for Ireland.

In his last years Tyndall often takes chloral hydrate to treat his insomnia. When bedridden and ailing, he dies from an accidental overdose of this drug on December 4, 1893, at the age of 73 and was buried at Haslemere, Surrey, England.

Tyndall is commemorated by a memorial, the Tyndalldenkmal, erected at an elevation of 7,680 ft. on the mountain slopes above the village of Belalp, where he had his holiday home, and in sight of the Aletsch Glacier, which he had studied.