St. Columba, an Irish monk, and twelve followers arrive on the tiny isle of Iona, barely three miles long by one mile wide, on May 12, 563, establishing a monastic community and building his first Celtic church. Iona has an influence out of all proportion to its size on the establishment of Christianity in Scotland, England and throughout mainland Europe.

Once settled, Columba sets about converting most of pagan Scotland and northern England to the Christian faith. Iona’s fame as a missionary centre and outstanding place of learning eventually spreads throughout Europe, turning it into a place of pilgrimage for several centuries to come. Iona becomes a sacred isle where kings of Scotland, Ireland and Norway are buried.

Columba is born of royal blood in 521 AD in Ireland, or Scotia as it is then called. He is the grandson of the Irish King Niall. He leaves Ireland for Scotland not as a missionary but as an act of self-imposed penance for a bloody mess he had caused at home. He had upset the king of Ireland by refusing to hand over a copy of the Gospel he had illegally copied, leading to a pitched battle in which Columba’s warrior family prevailed. Full of remorse for his actions and the deaths he had ultimately caused, he flees, ultimately settling on Iona as it is the first place he finds from which he is unable to see his native Ireland. One of the features on the island is even called “The Hill with its back to Ireland.”

Columba, however, is not the shy retiring type and sets about building Iona’s original abbey from clay and wood. In this endeavour he displays some strange idiosyncrasies, including banishing women and cows from the island. The abbey builders have to leave their wives and daughters on the nearby Eilean nam Ban (Woman’s Island). Stranger still, he also banishes frogs and snakes from Iona, although how he accomplishes this feat is not well documented.

The strangest claim of all however is that Columba is prevented from completing the building of the original chapel until a living person has been buried in the foundations. His friend Oran volunteers for the job and is duly buried. It is said that Columba later requests that Oran’s face be uncovered so he can bid a final farewell to his friend. Oran’s face is uncovered and he is found to be still alive but utters such blasphemous descriptions of Heaven and Hell that Columba orders that he be covered up immediately.

Over the centuries the monks of Iona produce countless elaborate carvings, manuscripts and Celtic crosses. Perhaps their greatest work is the exquisite Book of Kells, which dates from 800 AD, currently on display in Trinity College, Dublin. Shortly after this, in 806 AD, come the first of the Viking raids and many of the monks are slaughtered and their work destroyed.

The Celtic Church, lacking central control and organisation, diminishes in size and stature over the years to be replaced by the much larger and stronger Roman Church. Even Iona is not exempt from these changes and in 1203 a nunnery for the Order of the Black Nuns is established and the present-day Benedictine abbey, Iona Abbey, is built. The abbey is a victim of the Reformation and lay in ruins until 1899 when restoration is started.

No part of Columba’s original buildings have survived, however on the left hand side of the abbey entrance can be seen a small roofed chamber which is claimed to mark the site of the Columba’s tomb.

(From: “St. Columba and the Isle of Iona” by Ben Johnson, historic-uk.com, pictured is the Iona Abbey and Nunnery)

The

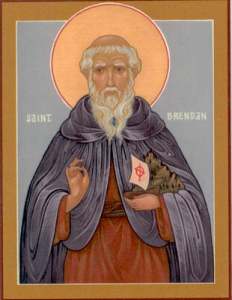

The  Saint Brendan of Clonfert

Saint Brendan of Clonfert