Major Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith (DSO) of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers is captured and executed by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on April 30, 1921 during the Irish War of Independence.

Major Geoffrey Lee Compton-Smith (DSO) of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers is captured and executed by the Irish Republican Army (IRA) on April 30, 1921 during the Irish War of Independence.

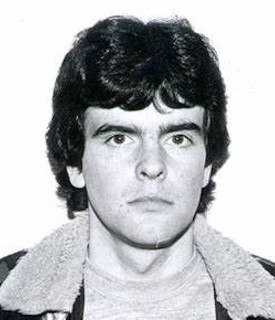

Compton-Smith was born in 1889 in South Kensington, London. After finishing school, he decides not to follow the family tradition of studying law. He actually wants to become an artist, but his father insists that he join the army. He studies at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst and during World War I his regiment is sent to France. In 1917 he is wounded at the Battle of Arras, but he continues to fight on. He is awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO). In 1919 he is sent to serve in Ireland during the Irish War of Independence.

In 1919 Compton-Smith is commander of the British Army base at Ballyvonane, near Buttevant, but he is also an intelligence officer. As an officer he also sometimes presides over courts martial. In January 1921, for instance, three IRA volunteers are tried by him for involvement in the ambush at Shinanagh, near Charleville, and he sentences them each to six months.

February 1921 is a bad time for the IRA in County Cork. They suffer major losses at the ambushes at Clonmult and Mourne Abbey, and several volunteers are taken prisoner, four of whom are sentenced to death. The IRA believes that these death sentences might be commuted if a British officer is held as a hostage. This leads to the capture of Compton-Smith. On April 16, 1921 he travels to Blarney, supposedly on a sketching trip but actually to meet a nurse in Victoria Barracks with whom he is having an affair. The IRA has spies in Victoria Barracks who likely tip off the IRA that Compton-Smith is coming to Blarney. A squad led by Frank Busteed easily capture him after he gets off the train.

Busteed then meets with Jackie O’Leary, the IRA battalion commander. It is decided that Donoughmore is the perfect place to keep a hostage, because parts of the parish are remote and the IRA is strong there.

On April 18, under the cover of darkness, Compton-Smith is transferred by car to Knockane House, an abandoned big house in Donoughmore. The following night he is moved again, this time by pony and trap, to Barrahaurin, a remote townland in the Boggeragh Mountains. He is kept there for the last eleven days of his life, on the small farm of Jack and Mary Moynihan. He is held prisoner in a shed, always under guard. Every evening he is brought into the house, where he eats and stays at the fireside. He and his guards have conversations about history and politics.

The four IRA prisoners are executed on April 28, 1921. On April 30, O’Leary informs Compton-Smith that he is going to be executed. He then writes a final letter to his wife. He tells her that he will die with her name on his lips and her face before his eyes and that he will “die like an Englishman and a soldier.” He also writes a letter to his regiment and one to Lt. General Strickland.

After finishing his letters, Compton-Smith is led up into Barrahaurin bog behind the Moynihan house, to a place where his grave had already been dug, and is given a final cigarette. In his witness statement Maurice Brew writes, “When removed to the place of execution he placed his cigarette case in his breast pocket of his tunic … He then lighted a cigarette and said that when he dropped the cigarette it could be taken as a signal by the execution squad to open fire.”

It is not until late May, following the discovery of the cache of letters in a Dublin raid, that the Compton-Smith family is informed of his death. His father, William, then starts a campaign to find his son’s body. He wrote letters to MPs and to the British Army, seeking information and help. He also writes to Erskine Childers but gets no reply. He offers a reward of £500 for information, but only The Irish Times agrees to print his advertisement.

In November 1921 a cousin of Compton-Smith’s wife, Gladys, meets Michael Collins in London and asks him for help in finding the body. Correspondence between Collins and the Compton-Smith family suggests that Collins is trying to help in 1922, but he fails to get any results before he is assassinated at Béal na Bláth later that same year.

On March 3, 1926 Compton-Smith’s grave is discovered by the Gardaí. The newspapers report that the remains, because of the conditions of the bog, “were not so badly decomposed as to render identification impossible.” The body is brought to Collins Barracks in Cork. On March 5 the Gardaí send a telegram to the Compton-Smiths, informing them that the body has been located.

The reburial of Compton-Smith is carried out with great dignity on March 19, 1926. The Irish Army escorts the coffin from Collins Barracks to Penrose Quay, where British forces from Spike Island take the coffin on board a boat. While the boat travels down the River Lee, the Irish Army’s guard of honour presents arms and sounds the “Last Post.” The British then bring the coffin to Carlisle Fort, near Whitegate, where it was buried in the in the British Military Cemetery with full military honours.

Michael Joseph O’Rahilly,

Michael Joseph O’Rahilly,

The last major body of Irish Catholic troops under

The last major body of Irish Catholic troops under

The

The

The

The  Captain

Captain