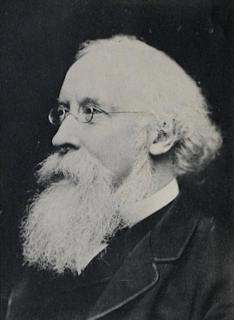

Whitley Stokes, CSI, CIE, FBA, Irish lawyer and Celtic scholar, is born at 5 Merrion Square, Dublin, on February 28, 1830.

Stokes is a son of William Stokes (1804–78), and a grandson of Whitley Stokes, a physician and anti-Malthusian (1763–1845), each of whom is Regius Professor of Physic at Trinity College Dublin (TCD). His sister, Margaret Stokes, is a writer and archaeologist.

Stokes is educated at St. Columba’s College where he is taught the Irish language by Denis Coffey, author of Primer of the Irish Language. Through his father he comes to know the Irish antiquaries Samuel Ferguson, Eugene O’Curry, John O’Donovan and George Petrie. He enters Trinity College Dublin in 1846 and graduates with a BA in 1851. His friend and contemporary Rudolf Thomas Siegfried (1830–63) becomes assistant librarian at TCD in 1855, and the college’s first professor of Sanskrit in 1858. Stokes likely learns both Sanskrit and comparative philology from Siegfried, thus acquiring a skill-set rare among Celtic scholars in Ireland at the time.

Stokes qualifies for the bar at Inner Temple. His instructors in the law are Arthur Cayley, Hugh McCalmont Cairns, and Thomas Chitty. He becomes an English barrister on November 17, 1855, practicing in London before going to India in 1862, where he fills several official positions. In 1865 he marries Mary Bazely by whom he has four sons and two daughters. One of his daughters, Maïve, compiles a book of Indian Fairy Tales in 1879 when she is 12 years old, based on stories told to her by her Indian ayahs and a man-servant. It also includes some notes by Mrs. Mary Stokes. Mary dies while the family is still living in India. In 1877, Stokes is appointed legal member of the viceroy’s council, and he drafts the codes of civil and criminal procedure and does much other valuable work of the same nature. In 1879 he becomes president of the commission on Indian law. Nine books he writes on Celtic studies are published in India. He returns to settle permanently in London in 1881 and marries Elizabeth Temple in 1884. In 1887 he is made a Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI), and two years later an Order of the Indian Empire (CIE). He is an original fellow of the British Academy, an honorary fellow of Jesus College, Oxford and foreign associate of the Institut de France.

Stokes is perhaps most famous as a Celtic scholar, and in this field he works both in India and in England. He studies Irish, Breton and Cornish texts. His chief interest in Irish is as a source of material for comparative philology. Despite his learning in Old Irish and Middle Irish, he never acquires Irish pronunciation and never masters Modern Irish. In the hundred years since his death he continues to be a central figure in Celtic scholarship. Many of his editions have not been superseded during this time and his total output in Celtic studies comes to over 15,000 pages. He is a correspondent and close friend of Kuno Meyer from 1881 onwards. With Meyer he establishes the journal Archiv für celtische Lexicographie and is the co-editor, with Ernst Windisch, of the Irische Texteseries. In 1876 his translation of Vita tripartita Sancti Patricii, along with a written introduction, is published.

In 1862 Stokes is awarded the Cunningham Medal by the Royal Irish Academy.

Stokes dies at his London home, 15 Grenville Place, Kensington, on April 13, 1909, and is buried in Paddington Old Cemetery, Willesden Lane, where his grave is marked by a Celtic cross. Another Celtic cross is erected as a memorial to him at St. Fintan’s Cemetery, Sutton, Dublin. The Gaelic League newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis calls him “the greatest of the Celtologists” and expresses pride that an Irishman has excelled in a field which is at that time dominated by continental scholars. In 1929 the Canadian scholar James F. Kenney describes him as “the greatest scholar in philology that Ireland has produced, and the only one that may be ranked with the most famous of continental savants.”

A conference entitled “Ireland, India, London: The Tripartite Life of Whitley Stokes” takes place at the University of Cambridge on September 18-19, 2009. The event is organised to mark the centenary of Stokes’s death. A volume of essays based on the papers delivered at this conference, The Tripartite Life of Whitley Stokes (1830–1909), is published by Four Courts Press in autumn 2011.

In 2010 Dáibhí Ó Cróinín publishes Whitley Stokes (1830–1909): The Lost Celtic Notebooks Rediscovered, a volume based on the scholarship in Stokes’s 150 notebooks which had been resting unnoticed at the Leipzig University Library, Leipzig since 1919.