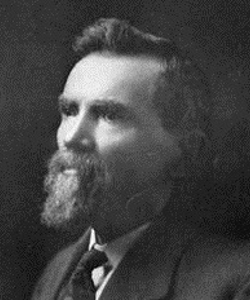

John Thomas Browne, Irish-born merchant and politician, dies in Houston, Texas on August 19, 1941. He serves on the Houston City Council, serves two terms as Mayor of Houston, and serves three terms in the Texas House of Representatives.

Browne is born March 23, 1845 in Ballylanders, County Limerick to Michael and Winifred (Hennessy) Browne. His family emigrates to the United States in October 1851. Not long after arriving in New Orleans, his father dies. In 1852, Winifred relocates with her five children to Houston to be closer to family of her mother.

Browne spends much of the 1850s on Spann Plantation in Washington County, Texas at the behest of Father Gunnard, where he also receives an education. At age fourteen in 1859, he leaves the plantation and finds work hauling bricks in Madison County, Texas. He returns to Houston to first work as a baggage hauler, then performs messenger duties for Commercial and Southwestern Express Company before settling in at the Houston and Texas Central Railroad.

Browne joins Company B of the Second Texas Infantry in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. He serves in Houston, detached from his unit, maintaining employment with the Houston and Texas Central Railroad, but in a new capacity as a fireman. He is briefly dispatched to the defense of Galveston, Texas. He is officially released from military duty in Houston on June 27, 1865.

Browne returns to messenger service in Houston after the Civil War. He works for Adams Express Company, then for Southern Express Company. He transitions into the grocery business first as a bookkeeper and clerk for H.P. Levy.

Browne is elected to the Houston City Council, representing the Fifth Ward while chairing the Finance Committee in 1887. He runs for Mayor of Houston in 1892 and wins in a landslide: 3900 to 600.

Browne’s first term as Mayor of Houston begins the same year as the Panic of 1893. He had campaigned on a platform of balancing the budget. The City of Houston runs budget deficits during Browne’s first term, but these deficits are proportionately lower than those in previous years. Browne is an advocate for lowering municipal utility bills through municipal ownership of the utilities. However, Browne abandons this option due to excessive costs for building a new waterworks and electrical power plant. He refocuses his efforts on a policy of dedicating all capital spending on street paving and sewerage.

Browne proposes converting the Houston Volunteer Firefighters to a professional department under municipal management. The City of Houston would be required to buy existing equipment and horses from the volunteer department, but can lease firehouses rather than buy them. The Houston City Council drafts an ordinance and passes it.

Browne represents Houston in the Texas House of Representatives from 1897 to 1899, and again in 1907. He is a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Knights of Columbus.

John Thomas Browne dies on August 19, 1941 of pneumonia in Houston. He is buried at Glenwood Cemetery in Houston. He is survived by six children and thirty-eight grandchildren. In 1979 his former residence in the Fifth Ward is used by an Italian American-owned grocery, Orlando’s Grocery.