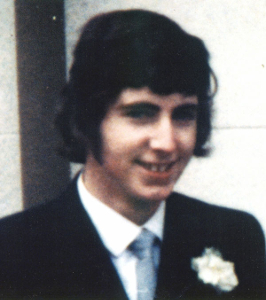

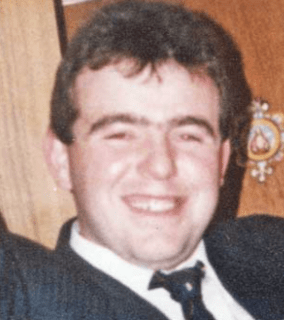

Gerard Patrick Martin McCaughey, Sinn Féin councillor and volunteer in the East Tyrone Brigade of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), is killed by undercover British Army soldiers in County Armagh on October 9, 1990, along with fellow IRA volunteer Dessie Grew.

McCaughey, from Aughnagar, Galbally, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, is born on February 24, 1967, the oldest son of Owen and Bridget McCaughey. He is a boyhood friend of several of the “Loughgall Martyrs” including Declan Arthurs, Seamus Donnelly, Tony Gormley and Eugene Kelly, with whom he travels to local discos and football matches when they are growing up.

McCaughey is a talented Gaelic football player who plays for local side Galbally Pearses and is also selected for the Tyrone minor Gaelic team.

McCaughey is elected as a Sinn Féin councillor for Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council and at the time is the youngest elected representative on the island of Ireland.

Two months prior to his shooting, McCaughey is disqualified from holding his office on the council as he had failed to appear for a monthly council meeting. After his death, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) reveals the explanation behind his disappearance. He had been shot and wounded in a shoot-out with undercover British Army security forces near Cappagh, County Tyrone. He is then taken south across the Irish border into the Republic of Ireland where he is given hospital treatment and therefore unable to attend the meetings.

Ulster Unionist MP and fellow Dungannon councillor Ken Maginnis alleges that McCaughey had conspired to kill him while both sat as councillors.

McCaughey is shot dead on October 9, 1990, along with Dessie Grew, in an operation by undercover British soldiers. A secret undercover intelligence unit named 14 Intelligence Company, also known as the DET, are monitoring three AK-47s at a farm building in a rural part of County Armagh and are aware that the pair are due to remove the guns.

As McCaughey and Grew are approaching an agricultural shed which is being used to grow mushrooms and also thought to be an IRA arms dump, as many as 200 shots are fired at the two men. British Army reports of the shooting state that the two men left the shed holding two rifles. Republican sources state the men were unarmed.

McCaughey is buried at Galbally Cemetery in October 1990.

The family of McCaughey claims that he and Grew were ambushed after a stakeout by the Special Air Service (SAS). In January 2002, Justice Weatherup, a Northern Ireland High Court judge, orders that official military documents relating to the shooting should be disclosed. However, Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) Chief Constable Hugh Orde has the ruling overturned on appeal in January 2005.

Fellow Sinn Féin representative, Francie Molloy, replaces McCaughey on Dungannon Council after a by-election is held following McCaughey’s death.

In January 2007, the lawyers representing McCaughey and another volunteer, Pearse Jordan, apply to the House of Lords to challenge the details of how the inquests into their deaths are to proceed.

McCaughey’s father, Owen, seeks to compel Chief Constable Hugh Orde to produce key documents including intelligence reports relevant to the shooting and the report of the RUC’s investigating officer.

In 2010, a commemorative portrait of McCaughey is unveiled in the mayor’s parlour at Dungannon council.