John Hely (later Hely-Hutchinson), Irish lawyer, statesman, and Provost of Trinity College Dublin, dies on September 4, 1794 at Buxton, Derbyshire, England.

John Hely (later Hely-Hutchinson), Irish lawyer, statesman, and Provost of Trinity College Dublin, dies on September 4, 1794 at Buxton, Derbyshire, England.

Hely is born in 1724 at Gortroe, Mallow, son of Francis Hely, a gentleman of County Cork. He is educated at Trinity College Dublin (BA 1744) and is called to the Irish bar in 1748. He takes the additional name of Hutchinson upon his marriage in 1751 to Christiana Nixon, heiress of her uncle, Richard Hutchinson.

Hely-Hutchinson is elected member of the Irish House of Commons for the borough of Lanesborough in 1759, but from 1761 to 1790 he represents Cork City. He at first attaches himself to the patriotic party in opposition to the government, and although he afterwards joins the administration, he never abandons his advocacy of popular measures.

After a session or two in parliament he is made a privy councillor and prime Serjeant-at-law. From this time he gives a general, though by no means invariable, support to the government. In 1767 the ministry contemplates an increase of the army establishment in Ireland from 12,000 to 15,000 men, but the Augmentation Bill meets with strenuous opposition, not only from Henry Flood, John Ponsonby and the habitual opponents of the government, but from the Undertakers, or proprietors of boroughs, on whom the government has hitherto relied to secure them a majority in the House of Commons.

It therefore becomes necessary for Lord Townshend to turn to other methods for procuring support. Early in 1768 an English Act is passed for the increase of the army, and a message from King George III setting forth the necessity for the measure is laid before the House of Commons in Dublin. An address favourable to the government policy is, however, rejected as Hely-Hutchinson, together with the speaker and the attorney general, do their utmost both in public and private to obstruct the bill. Parliament is dissolved in May 1768, and the lord lieutenant sets about the task of purchasing or otherwise securing a majority in the new parliament. Peerages, pensions and places are bestowed lavishly on those whose support could be thus secured. Hely-Hutchinson is won over by the concession that the Irish army should be established by the authority of an Irish act of parliament instead of an English one.

The Augmentation Bill is carried in the session of 1769 by a large majority. Hely-Hutchinson’s support had been so valuable that he receives as reward an addition of £1,000 a year to the salary of his sinecure of alnager, a major’s commission in a cavalry regiment, and a promise of the Secretaryship of State. He is at this time one of the most brilliant debaters in the Irish parliament and is enjoying an exceedingly lucrative practice at the bar. This income, however, together with his well-salaried sinecure, and his place as prime serjeant, he surrenders in 1774 to become provost of Trinity College, although the statute requiring the provost to be in holy orders has to be dispensed with in his favour.

For this great academic position Hely-Hutchinson is in no way qualified and his appointment to it for purely political service to the government is justly criticised with much asperity. His conduct in using his position as provost to secure the parliamentary representation of the university for his eldest son brings him into conflict with Patrick Duigenan, while a similar attempt on behalf of his second son in 1790 leads to his being accused before a select committee of the House of Commons of impropriety as returning officer. But although without scholarship Hely-Hutchinson is an efficient provost, during whose rule material benefits are conferred on Trinity College.

Hely-Hutchinson continues to occupy a prominent place in parliament, where he advocates free trade, the relief of the Catholics from penal legislation, and the reform of parliament. He is one of the very earliest politicians to recognise the soundness of Adam Smith‘s views on trade and he quotes from the Wealth of Nations, adopting some of its principles, in his Commercial Restraints of Ireland, published in 1779, which William Edward Hartpole Lecky pronounces one of the best specimens of political literature produced in Ireland in the latter half of the 18th century.

In the same year, the economic condition of Ireland being the cause of great anxiety, the government solicits from several leading politicians their opinion on the state of the country with suggestions for a remedy. Hely-Hutchinson’s response is a remarkably able state paper, which also shows clear traces of the influence of Adam Smith. The Commercial Restraints, condemned by the authorities as seditious, goes far to restore Hely-Hutchinson’s popularity which has been damaged by his greed of office. Not less enlightened are his views on the Catholic question. In a speech in parliament on Catholic education in 1782 the provost declares that Catholic students are in fact to be found at Trinity College, but that he desires their presence thereto be legalised on the largest scale.

In 1777 Hely-Hutchinson becomes Secretary of State. When Henry Grattan in 1782 moves an address to the king containing a declaration of Irish legislative independence, he supports the attorney general’s motion postponing the question. On April 16, however, after the Easter recess, he reads a message from the Lord Lieutenant, the William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland, giving the king’s permission for the House to take the matter into consideration, and he expresses his personal sympathy with the popular cause which Grattan on the same day brings to a triumphant issue. Hely-Hutchinson supports the opposition on the regency question in 1788, and one of his last votes in the House is in favour of parliamentary reform. In 1790 he exchanges the constituency of Cork for that of Taghmon in County Wexford, for which borough he remains member until his death at Buxton, Derbyshire on September 4, 1794.

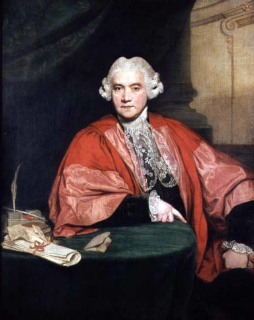

(Pictured: Portrait, oil on canvas, of John Hely-Hutchinson (1724–1794) by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792))

William Edward Hartpole Lecky

William Edward Hartpole Lecky