The trial of Oscar Wilde on charges of homosexuality, then considered a crime, begins at the Old Bailey on April 26, 1895.

The trial of Oscar Wilde on charges of homosexuality, then considered a crime, begins at the Old Bailey on April 26, 1895.

With a warrant for Wilde’s arrest on charges of sodomy and gross indecency having been issued, Robbie Ross finds Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel, Knightsbridge, with Reginald Turner. Both men advise Wilde to go at once to Dover and try to get a boat to France. His mother advises him to stay and fight. Wilde, lapsing into inaction, can only say, “The train has gone. It’s too late.” Wilde is arrested for “gross indecency” under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, a term meaning homosexual acts not amounting to buggery, an offence under a separate statute. At Wilde’s instruction, Ross and Wilde’s butler force their way into the bedroom and library of 16 Tite Street, packing some personal effects, manuscripts, and letters. Wilde is then imprisoned on remand at HM Prison Holloway where he receives daily visits from his partner, Lord Alfred Douglas.

Events move quickly and his prosecution opens on April 26, 1895. Wilde pleads not guilty. He has already begged Douglas to leave London for Paris, but Douglas complains bitterly, even wanting to give evidence. He is pressed to go and soon flees to the Hotel du Monde. Fearing persecution, Ross and many others also leave the United Kingdom during this time.

Under cross examination by Charles Gill, Wilde is at first hesitant, but then eloquently responds to Gill’s question about the meaning of “the love that dare not speak its name.” Wilde replies, “‘The love that dare not speak its name” in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art, like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as ‘the love that dare not speak its name,’ and on that account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an older and a younger man, when the older man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so, the world does not understand. The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

Wilde’s response is counter-productive in a legal sense as it only serves to reinforce the charges of homosexual behaviour. The trial ends with the jury unable to reach a verdict. Wilde’s counsel, Sir Edward Clarke, is finally able to get a magistrate to allow Wilde and his friends to post bail. The Reverend Stewart Headlam puts up most of the £5,000 surety required by the court, having disagreed with Wilde’s treatment by the press and the courts. Wilde is freed from Holloway and, shunning attention, goes into hiding at the house of Ernest and Ada Leverson, two of his firm friends. Edward Carson approaches Frank Lockwood QC, the Solicitor General and asks, “Can we not let up on the fellow now?” Lockwood answers that he would like to do so, but fears that the case has become too politicised to be dropped.

The final trial is presided over by Alfred Wills. On May 25, 1895 Wilde and Alfred Taylor are convicted of gross indecency and sentenced to two years’ hard labour. The judge describes the sentence, the maximum allowed, as “totally inadequate for a case such as this,” and that the case is “the worst case I have ever tried.” Wilde responds, “And I? May I say nothing, my Lord?” but it is drowned out by cries of “Shame” in the courtroom.

Oscar Wilde enters prison on May 25, 1895 and is released on May 18, 1897.

(Pictured: Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas)

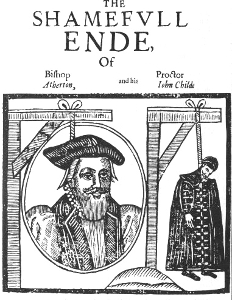

John Atherton, Anglican Bishop of Waterford and Lismore in the Church of Ireland, is executed on December 5, 1640, on a charge of immorality.

John Atherton, Anglican Bishop of Waterford and Lismore in the Church of Ireland, is executed on December 5, 1640, on a charge of immorality.

The trial of

The trial of