The Tullyvallen massacre takes place on September 1, 1975, when Irish republican gunmen attack an Orange Order meeting hall at Tullyvallen, near Newtownhamilton in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The Orange Order is an Ulster Protestant and unionist brotherhood. Five Orangemen are killed and seven wounded in the shooting. The “South Armagh Republican Action Force” claims responsibility, saying it is retaliation for a string of attacks on Catholic civilians by Loyalists. It is believed members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) carried out the attack, despite the organisation being on ceasefire.

On February 10, 1975, the Provisional IRA and British government enter into a truce and restart negotiations. The IRA agrees to halt attacks on the British security forces, and the security forces mostly end their raids and searches. There is a rise in sectarian killings during the truce. Loyalists, fearing they are about to be forsaken by the British government and forced into a united Ireland, increase their attacks on Irish Catholics/nationalists. They hope to force the IRA to retaliate and thus end the truce. Some IRA units concentrate on tackling the loyalists. The fall-off of regular operations causes unruliness within the IRA and some members, with or without permission from higher up, engage in tit-for-tat killings.

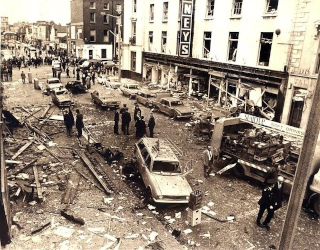

On August 22, loyalists kill three Catholic civilians in a gun and bomb attack on a pub in Armagh. Two days later, loyalists shoot dead two Catholic civilians after stopping their car at a fake British Army checkpoint in the Tullyvallen area. Both of these attacks are linked to the Glenanne gang. On August 30, loyalists kill two more Catholic civilians in a gun and bomb attack on a pub in Belfast.

On the night of September 1, a group of Orangemen are holding a meeting in their isolated Orange hall in the rural area of Tullyvallen. At about 10:00 PM, two masked gunmen burst into the hall armed with assault rifles and spray it with bullets while others stand outside and fire through the windows. The Orangemen scramble for cover. One of them is an off-duty Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) officer. He returns fire with a pistol and believes he hit one of the attackers. Five of the Orangemen, all Protestant civilians, are killed while seven others are wounded. Before leaving, the attackers also plant a two-pound bomb outside the hall, but it fails to detonate.

The victims are John Johnston (80), James McKee (73) and his son William McKee (40), Nevin McConnell (48), and William Herron (68) who dies two days later. They all belong to Tullyvallen Guiding Star Temperance Orange Lodge. Three of the dead are former members of the Ulster Special Constabulary.

A caller to the BBC claims responsibility for the attack on behalf of the “South Armagh Republican Action Force” or “South Armagh Reaction Force,” saying it is retaliation for “the assassinations of fellow Catholics.” The Irish Times reports on September 10: “The Provisional IRA has told the British government that dissident members of its organisation were responsible” and “stressed that the shooting did not have the consent of the organisation’s leadership.”

In response to the attack, the Orange Order calls for the creation of a legal militia, or “Home Guard,” to deal with republican paramilitaries.

Some of the rifles used in the attack are later used in the Kingsmill massacre in January 1976, when ten Protestant workmen are killed. Like the Tullyvallen massacre, it is claimed by the “South Armagh Reaction Force” as retaliation for the killing of Catholics elsewhere.

In November 1977, 22-year-old Cullyhanna man John Anthony McCooey is convicted of driving the gunmen to and from the scene and of IRA membership. He is also convicted of involvement in the killings of Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldier Joseph McCullough, chaplain of Tullyvallen Orange lodge, in February 1976, and UDR soldier Robert McConnell in April 1976.

The

The