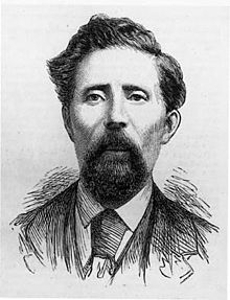

Michael Manning, Irish murderer, becomes the twenty-ninth and last person to be executed in the Republic of Ireland on April 20, 1954.

Manning, a 25-year-old carter from Johnsgate in Limerick, County Limerick, is found guilty of the rape and murder of Catherine Cooper, a 65-year-old nurse who works at Barrington’s Hospital in the city, in February 1954. Nurse Cooper’s body is discovered on November 18, 1953, in the quarry under the New Castle, Dublin Road, Castletroy. She is found to have choked on grass stuffed into her mouth to keep her from screaming during the committal of the crime.

Manning expresses remorse at the crime which he does not deny. By his own account, he is making his way home on foot after a day’s drinking in The Black Swan, Annacotty when he sees a woman he does not recognise walking alone. “I suddenly lost my head and jumped on the woman and remember no more until the lights of a car shone on me.” He flees at this point but is arrested within hours, after his distinctive hat is found at the scene of the crime.

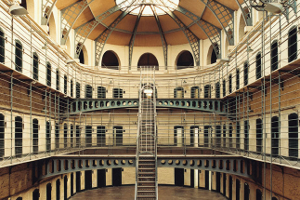

Although Manning makes an impassioned plea for clemency in a letter to Minister for Justice Gerald Boland, his request is denied despite it also being supported by Nurse Cooper’s family. The execution by hanging is duly carried out on April 20, 1954, in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin by Albert Pierrepoint, who has traveled from Britain where he is one of three Senior Executioners.

Frank Prendergast, subsequently Teachta Dála (TD) for Limerick East who knew Manning well, recalls later, “Friends of mine who worked with me, I was serving my time at the time, went up to visit him on the Sunday before he was hanged. And they went to Mass and Holy Communion together and they played a game of handball that day. He couldn’t have been more normal.”

Manning leaves a wife who is pregnant at the time of the murder. His body is buried in an unmarked grave in a yard at Mountjoy Prison.

The death penalty is abolished in 1964 for all but the murder of gardaí, diplomats and prison officers. It is abolished by statute for these remaining offences in 1990 and is finally expunged from the Constitution of Ireland by approval by referendum of the Twenty-First Amendment on June 7, 2001.

The hanging of Michael Manning inspires a play by Ciaran Creagh. Creagh’s father, Timothy, is one of the two prison officers who stays with Michael Manning on his last night and Last Call is loosely based on what happened. It is shown in Mountjoy Prison’s theatre for three nights in June 2006.