On September 19, 1863, the 5th Confederate Infantry, consisting of a large number of Irish from Memphis, fight in one of the bloodiest battles of the American Civil War at Chickamauga, Georgia. One of the commanders is Cork-born Patrick Cleburne whom historians universally recognize as one of the most capable officers on either side during the awful conflict, although Chickamauga might not have been his finest hour. Cleburne is known as the “Stonewall of the West.” He is one of six Confederate generals to die in the Battle of Franklin.

The Battle of Chickamauga marks the end of a Union Army offensive, the Chickamauga campaign, in southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia. It is the first major battle of the war fought in Georgia, the most significant Union Army defeat in the Western Theater, and involves a high number of casualties, second only to the casualties suffered at the Battle of Gettysburg.

The battle is fought between the Army of the Cumberland, one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater, under Major General William Rosecrans and the Confederate Army of Tennessee under General Braxton Bragg and is named for Chickamauga Creek. The West Chickamauga Creek meanders near and forms the southeast boundary of the battle area and the park in northwest Georgia. The South Chickamauga ultimately flows into the Tennessee River about 3.5 miles northeast of downtown Chattanooga.

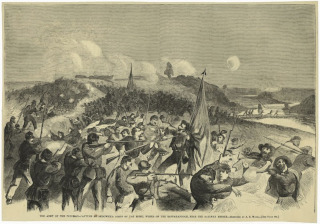

After his successful Tullahoma campaign, Rosecrans renews the offensive, aiming to force the Confederates out of Chattanooga. In early September, he consolidates his forces scattered in Tennessee and Georgia and forces Bragg’s army out of Chattanooga, heading south. The Union troops follow it and brush with it at Davis’s Cross Roads. Bragg is determined to reoccupy Chattanooga and decides to meet a part of Rosecrans’s army, defeat it, and then move back into the city. On September 17 he heads north, intending to attack the isolated XXI Corps. As Bragg marches north on September 18, his cavalry and infantry fight with Union cavalry and mounted infantry, which are armed with Spencer repeating rifles. The two armies fight at Alexander’s Bridge and Reed’s Bridge, as the Confederates try to cross the West Chickamauga Creek.

Fighting begins in earnest on the morning of September 19. Bragg’s men strongly assault but cannot break the Union Army line. The next day, Bragg resumes his assault. In late morning, Rosecrans is misinformed that he has a gap in his line. In moving units to shore up the supposed gap, Rosecrans accidentally creates an actual gap directly in the path of an eight-brigade assault on a narrow front by Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet, whose corps has been detached from the Army of Northern Virginia. In the resulting rout, Longstreet’s attack drives one-third of the Union Army, including Rosecrans himself, from the field.

Union Army units spontaneously rally to create a defensive line on Horseshoe Ridge (“Snodgrass Hill“), forming a new right wing for the line of Major General George H. Thomas, who assumes overall command of remaining forces. Although the Confederates launch costly and determined assaults, Thomas and his men hold until twilight. Union forces then retire to Chattanooga while the Confederates occupy the surrounding heights, besieging the city.

Thomas withdraws the remainder of his units to positions around Rossville Gap after darkness falls. The Army of Tennessee camps for the night, unaware that the Union Army has slipped from their grasp. Bragg is not able to mount the kind of pursuit that would be necessary to cause Rosecrans significant further damage. Many of his troops had arrived hurriedly at Chickamauga by rail, without wagons to transport them, and many of the artillery horses had been injured or killed during the battle. The Tennessee River is now an obstacle to the Confederates and Bragg has no pontoon bridges to affect a crossing. Bragg’s army pauses at Chickamauga to reorganize and gather equipment lost by the Union Army. Although Rosecrans had been able to save most of his trains, large quantities of ammunition and arms are left behind.

Army of Tennessee historian Thomas L. Connelly has criticized Bragg’s performance, claiming that for over four hours on the afternoon of September 20, he missed several good opportunities to prevent the Union escape, such as by a pursuit up the Dry Valley Road to McFarland’s Gap, or by moving a division to the north to seize the Rossville Gap or McFarland’s Gap via the Reed’s Bridge Road.

The battle is damaging to both sides in proportions roughly equal to the size of the armies: Union losses are 16,170 (1,657 killed, 9,756 wounded, and 4,757 captured or missing), Confederate losses are 18,454 (2,312 killed, 14,674 wounded, and 1,468 captured or missing). Among the dead are Confederate generals Benjamin Hardin Helm (husband of Abraham Lincoln‘s sister-in-law), James Deshler, and Preston Smith, and Union general William H. Lytle. Confederate general John Bell Hood, who had already lost the use of his left arm from a wound at Gettysburg, is severely wounded with a bullet in his leg, requiring it to be amputated. Although the Confederates are technically the victors, driving Rosecrans from the field, Bragg did not achieve his objectives of destroying Rosecrans or of restoring Confederate control of East Tennessee, and the Confederate Army suffers casualties that they can ill afford.