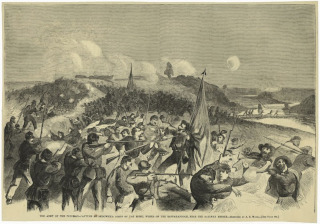

The Irish 6th Louisiana fights at the Second Battle of Rappahannock Station on November 7, 1863, near the village of Rappahannock Station (now Remington, Virginia), on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. The battle is between Confederate forces under Maj. Gen. Jubal Early and Union forces under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick as part of the Bristoe campaign of the American Civil War. The battle results in a victory for the Union.

Following the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, the Union and Confederate armies drift south and for three months spar with one another on the rolling plains of northern Virginia. In late October, General Robert E. Lee withdraws his Confederate army behind the Rappahannock River, a line he hopes to maintain throughout the winter. A single pontoon bridge at the town of Rappahannock Station is the only connection Lee retains with the northern bank of the river.

The Union Army of the Potomac‘s commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, divides his forces just as Lee expects. He orders Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick to attack the Confederate position at Rappahannock Station while Maj. Gen. William H. French forces a crossing five miles downstream at Kelly’s Ford. Once both Sedgwick and French are safely across the river, the reunited army is to proceed to Brandy Station.

The operation goes according to plan. Shortly after noon on November 7, French drives back Confederate defenders at Kelly’s Ford and crosses the river. As he does so, Sedgwick advances toward Rappahannock Station. Lee learns of these developments sometime after noon and immediately puts his troops in motion to meet the enemy. His plan is to resist Sedgwick with a small force at Rappahannock Station while attacking French at Kelly’s Ford with the larger part of his army. The success of the plan depends on his ability to maintain the Rappahannock Station bridgehead until French is defeated.

Sedgwick first engages the Confederates at 3:00 PM when Maj. Gen. Albion P. Howe‘s division of the VI Corps drives in Confederate skirmishers and seizes a range of high ground three-quarters of a mile from the river. Howe places Union batteries on these hills that pound the enemy earthworks with a “rapid and vigorous” fire. Confederate guns across the river return the fire, but with little effect.

Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s division occupies the bridgehead defenses that day. Early posts Brig. Gen. Harry T. Hays‘s Louisiana brigade and Captain Charles A. Green’s four-gun Louisiana Guard Artillery in the works and at 4:30 PM reinforces them with three North Carolina regiments led by Colonel Archibald C. Godwin. The addition of Godwin’s troops increases the number of Confederate defenders at the bridgehead to nearly 2,000.

Sedgwick continues shelling the Confederates throughout the late afternoon, but otherwise he shows no disposition to attack. As the day draws to a close, Lee becomes convinced that the movement against the bridgehead is merely a feint to cover French’s crossing farther downstream. He is mistaken. At dusk the shelling stops, and Sedgwick’s infantry rushes suddenly upon the works. Col. Peter Ellmaker’s brigade advances adjacent to the railroad, precedes by skirmishers of the 6th Maine Volunteer Infantry. At the command “Forward, double-quick!” they surge over the Confederate works and engage Hays’s men in hand-to-hand combat. Without assistance, the 6th Maine breaches the Confederate line and plants its flags on the parapet of the easternmost redoubt. Moments later the 5th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment swarms over the walls of the western redoubt, likewise, wresting it from Confederate control.

On the right, Union forces achieve comparable success. Just minutes after Ellmaker’s brigade penetrates Hays’s line, Col. Emory Upton‘s brigade overruns Godwin’s position. Upton reforms his lines inside the Confederate works and sends a portion of the 121st New York Volunteer Infantry to seize the pontoon bridge, while the rest of his command wheels right to attack the confused Confederate horde now massed at the lower end of the bridgehead.

Confederate resistance dissolves as hundreds of soldiers throw down their arms and surrender. Others seek to gain the opposite shore by swimming the icy river or by running the gauntlet of Union rifle fire at the bridge. Confederate troops south of the Rappahannock look on hopelessly as Union soldiers herd their comrades to the rear as prisoners of war.

In all, 1,670 Confederates are killed, wounded, or captured in the brief struggle, more than eighty percent of those engaged. Union casualty figures, by contrast, are small: 419 in all. The battle is as humiliating for the South as it is glorious for the North. Two of the Confederacy’s finest brigades, sheltered behind entrenchments and well supported by artillery, are routed and captured by an enemy force of equal size.

The Civil War Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved 856 acres of the battlefield where the First and Second Battles of Rappahannock Station were fought. The battleground for both battles is located along the Rappahannock River at Remington, VA and features visible earthworks as well as bridge and mill ruins. The earthworks at Remington are no longer there and more than 75% of the battlefield has been developed over.