Anna Parnell, younger sister of Irish Nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell, founds the Committee of the Ladies’ Land League, an auxiliary of the Irish National Land League, in Dublin on January 31, 1881. The organisation grows rapidly. By May 1881 there are 321 branches in Ireland, with branches also in Britain, the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

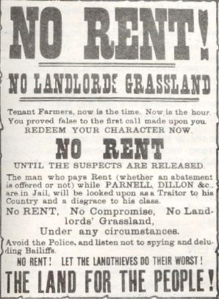

The organization is set up to take over the work of the Irish National Land League after its leadership is imprisoned. They raise money for the Land League prisoners and their dependants. They encourage women to resist eviction from their cottages. If families are evicted, the Ladies’ Land League provides wooden huts to the evicted families.

The ladies find themselves with additional work late in 1881. The Land League has started its own paper, United Ireland, in August 1881, but towards the end of the year the government tries to close it down. William O’Brien, the editor, continues to smuggle out copy from Kilmainham Gaol, but it falls to the ladies to get it printed. This is done first in London and then for a while in Paris. Eventually the ladies print and circulate it themselves from an office at 32 Lower Abbey Street.

On Sunday, March 12, 1881, just more than a month after the formation of the league, a pastoral letter of Archbishop of Dublin Edward McCabe is read out in all the churches of the diocese. It condemns the league in the strongest terms, deploring that “our Catholic daughters, be they matrons or virgins, are called forth, under the flimsy pretext of charity, to take their stand in the noisy street of life.” McCabe is not representative of all bishops, particularly Archbishop of Cashel Thomas Croke, a strong supporter of the original league. Croke publishes a letter in the Freeman’s Journal challenging the “monstrous imputations” in McCabe’s pastoral.

The dissension is revived somewhat in the summer of 1882. McCabe, now a Cardinal, and another bishop try to have a public condemnation of the Ladies’ Land League inserted into an address by the Catholic Bishops of Ireland in June. The other bishops resist on the basis that it would probably do more harm than good. They content themselves with expressing their hope that “the women of Ireland will continue to be the glory of their sex and the noble angels of stainless modesty.” When newspapers interpret this as a condemnation of the league, Croke writes again to the Freeman’s Journal to deny that this had been the intention of the bishops.

The order banning the Irish National Land League makes no direct reference to the Ladies’ Land League, but many police officers try to insist that the ban includes the women’s group. Eventually, on December 16, 1881, Inspector General Hillier of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) orders the police to stop the women’s meetings. Anna Parnell defiantly issues a notice to all Ladies’ Land League branches in the country calling on them all to hold a meeting on January 1, 1882.

The prominent resident magistrate, Major Clifford Lloyd, claims that the huts built for evicted tenants are being used as posts from which the evicted tenants can intimidate anyone who attempts to take over their vacated holdings. In April 1882, he threatens that anyone attempting to erect huts will be imprisoned. That month, Anne Kirke is sent down from Dublin to Tulla, County Clare, to oversee the erection of huts for a large number of evicted tenants. Lloyd has her arrested and imprisoned for three months.

The government does not wish to be seen to use the Coercion Act to imprison women, but another stratagem is used. In December 1881 21-year-old Hannah Reynolds is imprisoned under an ancient statute from the reign of Edward III, the original purpose of which was to keep prostitutes off the streets. The statute empowers magistrates to imprison “persons not of good fame” if they do not post bail as a guarantee of their good behavior. Since Reynolds claims her behavior is good, she refuses to pay bail and spends a month in Cork gaol. In all, thirteen women serve jail sentences under this statute.

On May 3, 1882, Parnell and other leaders are released from jail after agreeing to the Kilmainham Treaty. This includes some improvement in the 1881 Land Act. He now wishes to turn his attention more to the Home Rule question. The Irish National Land League is replaced by the Irish National League. Parnell also wants to see an end to the Ladies’ Land League. There had been increased violence while he was in jail, and he sees Anna as too radical. The organization has an overdraft of £5,000 which Parnell agrees to clear from central funds only if the organization is dissolved. At a meeting of the Central Committee on August 10, 1882, the Ladies’ Land League votes to dissolve itself. Anna Parnell herself is not in attendance at that meeting having suffered a physical and mental collapse after the sudden death of her sister Fanny the previous month.

The records of the Ladies’ Land League are lost to history in 1916. Jennie Wyse Power, who had served on the Central Committee, had kept them in her house in Henry Street, Dublin. When fire spreads from Sackville Street during the 1916 Easter Rising, her house is destroyed, and the records perish in the blaze.

(Pictured: Lady Land Leaguers at work at the Dublin office)

Joe Brady is hanged at

Joe Brady is hanged at

Lord Frederick Cavendish

Lord Frederick Cavendish The

The