The Loughinisland massacre takes place on June 18, 1994, in the small village of Loughinisland, County Down, Northern Ireland. Members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), a loyalist paramilitary group, burst into a pub with assault rifles and fire on the customers, killing six civilians and wounding five. The pub is targeted because it is frequented mainly by Catholics. The UVF claims the attack is retaliation for the killing of three UVF members by the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) two days earlier.

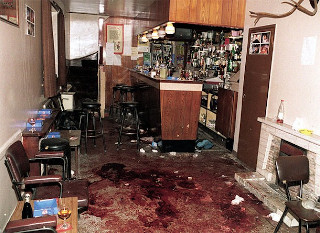

About 24 people are gathered in The Heights Bar, also known as O’Toole’s Pub, watching the Republic of Ireland vs. Italy in the 1994 FIFA World Cup. It is thus sometimes referred to as the “World Cup massacre.”

At 10:10 PM, two UVF members wearing boilersuits and balaclavas walk into the bar. One shouts “Fenian bastards!” and opens fire on the crowd with a vz. 58 assault rifle, spraying the small room with more than sixty bullets. Six men are killed outright, and five other people are wounded. Witnesses say the gunmen then run to a getaway car, “laughing.” One witness describes “bodies … lying piled on top of each other on the floor.” The dead were Adrian Rogan (34), Malcolm Jenkinson (52), Barney Green (87), Daniel McCreanor (59), Patrick O’Hare (35) and Eamon Byrne (39), all Catholic civilians. O’Hare is the brother-in-law of Eamon Byrne and Green is one of the oldest people to be killed during the Troubles.

The UVF claims responsibility within hours of the attack. It claims that an Irish republican meeting was being held in the pub and that the shooting was retaliation for the INLA attack. Police say there is no evidence the pub had links to republican paramilitary activity and say the attack is purely sectarian. Journalist Peter Taylor writes in his book Loyalists that the attack may not have been sanctioned by the UVF leadership. Police intelligence indicates that the order to retaliate came from the UVF leadership and that its ‘Military Commander’ had supplied the rifle used. Police believe the attack was carried out by a local UVF unit under the command of a senior member who reported to the leadership in Belfast.

The attack receives international media coverage and is widely condemned. Among those who send messages of sympathy are Pope John Paul II, Queen Elizabeth II and United States President Bill Clinton. Local Protestant families visit their wounded neighbours in the hospital, expressing their shock and disgust.

There have been allegations that police (Royal Ulster Constabulary) double agents or informants in the UVF were linked to the massacre and that police protected those informers by destroying evidence and failing to carry out a proper investigation. At the request of the victims’ families, the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland investigate the police. In 2011 the Ombudsman concludes that there were major failings in the police investigation, but no evidence that police colluded with the UVF. The Ombudsman does not investigate the role of informers and the report is branded a whitewash. The Ombudsman’s own investigators demand to be disassociated from it. The report is quashed, the Ombudsman replaced, and a new inquiry ordered.

In 2016, a new Ombudsman report concludes that there had been collusion between the police and the UVF, and that the investigation was undermined by the wish to protect informers but found no evidence police had foreknowledge of the attack. A documentary film about the massacre, No Stone Unturned, is released in 2017. It names the main suspects, one of whom is a member of the British Army and claims that one of the killers was an informer.