The Limerick Soviet exists for a two-week period from April 15 to April 27, 1919, and is one of a number of self-declared Irish soviets that are formed around Ireland between 1919 and 1923. At the beginning of the Irish War of Independence, a general strike is organised by the Limerick Trades and Labour Council, as a protest against the British Army‘s declaration of a “Special Military Area” under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which covers most of Limerick city and a part of the county. The soviet runs the city for the period, prints its own money and organises the supply of food.

From January 1919 the Irish War of Independence develops as a guerrilla conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) (backed by Sinn Féin‘s Dáil Éireann), and the British government. On April 6, 1919, the IRA tries to liberate Robert Byrne, who is under arrest by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) in a hospital, being treated for the effects of a hunger strike. In the rescue attempt Constable Martin O’Brien is fatally wounded, and another policeman is seriously injured. Byrne is also wounded and dies later the same day.

In response, on April 9 British Army Brigadier Griffin declares the city to be a Special Military Area, with RIC permits required for all wanting to enter and leave the city as of Monday, April 14. British Army troops and armoured vehicles are deployed in the city.

On Friday, April 11 a meeting of the United Trades and Labour Council, to which Byrne had been a delegate, takes place. At that meeting Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) representative Sean Dowling proposes that the trade unions take over Town Hall and have meetings there, but the proposal is not voted on. On Saturday, April 12 the ITGWU workers in the Cleeve’s factory in Lansdowne vote to go on strike. On Sunday, April 13, after a twelve-hour discussion and lobbying of the delegates by workers, a general strike is called by the city’s United Trades and Labour Council. Responsibility for the direction of the strike is devolved to a committee that describes itself as a soviet as of April 14. The committee has the example of the Dublin general strike of 1913 and “soviet” (meaning a self-governing committee) has become a popular term after 1917 from the soviets that had led to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

A transatlantic air race is being organised from Bawnmore in County Limerick at the same time but is cancelled. The assembled journalists from England and the United States take up the story of an Irish soviet and interview the organisers. The Trades Council chairman John Cronin is described as the “father of the baby Soviet.” Ruth Russell of the Chicago Tribune remarks on the religiosity of the strike committee, observes “the bells of the nearby St. Munchin’s Church tolled the Angelus and all the red-badged guards rose and blessed themselves.” The Sinn Féin Mayor of Limerick, Phons O’Mara, tells Russell there is no prospect of socialism, as “There can’t be, the people here are Catholics.”

The general strike is extended to a boycott of the troops. A special strike committee organises food and fuel supplies, prints its own money based on the British shilling, and publishes its own newspaper called The Worker’s Bulletin. The businesses of the city accept the strike currency. Cinemas open with the sign “Working under authority of the strike committee” posted. Local newspapers are allowed to publish once a week as long as they have the caption “Published by Permission of the Strike Committee.” Outside Limerick there is some sympathy in Dublin, but not in the main Irish industrial area around Belfast. The National Union of Railwaymen does not help.

On April 21 The Worker’s Bulletin remarks that “A new and perfect system of organisation has been worked out by a clever and gifted mind, and ere long we shall show the world what Irish workers are capable of doing when left to their own resources.” On Easter Monday 1919, the newspaper states “The strike is a worker’s strike and is no more Sinn Féin than any other strike.”

Liam Cahill argues, “The soviet attitude to private property was essentially pragmatic. So long as shopkeepers were willing to act under the soviet’s dictates, there was no practical reason to commandeer their premises.” While the strike is described by some as a revolution, Cahill adds, “In the end the soviet was basically an emotional and spontaneous protest on essentially nationalist and humanitarian grounds, rather than anything based on socialist or even trade union aims.”

After two weeks the Sinn Féin Lord Mayor of Limerick, Phons O’Mara, and the Catholic bishop Denis Hallinan call for the strike to end, and the Strike Committee issues a proclamation on April 27, 1919, stating that the strike is over.

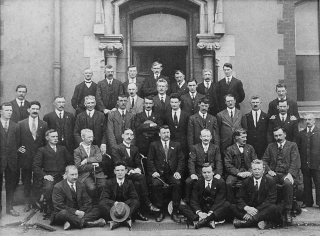

(Pictured: Photograph of Members of the 1919 Limerick Soviet, April 1919, Limerick City)