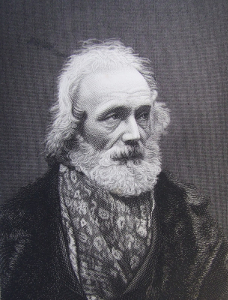

Maximilian Ulysses, Reichsgraf von Browne, Baron de Camus and Mountany, an Irish refugee, scion of the Wild Geese and an Austrian military officer, dies in Prague, Kingdom of Bohemia on June 26, 1757. He is one of the highest-ranking officers serving the Hapsburg Emperor during the middle of the 18th century and one of the most prominent Irish soldiers never to fight for Ireland.

Browne is born in Basel, Switzerland, the son of Count Ulysses von Browne (b. Limerick 1659) and his wife Annabella Fitzgerald, a daughter of the House of Desmond. Both families had been exiled from Ireland in the aftermath of the Nine Years’ War.

Browne’s early career is helped by family and marital connections. His father and his father’s brother, George (b. Limerick 1657), are created Counts of the Holy Roman Empire by Emperor Charles VI in 1716 after serving with distinction in the service of the Holy Roman Emperors. The brothers enjoy a lengthy, close friendship with John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, who is primarily responsible for their establishment in the Imperial Service of Austria. On his father’s death he becomes third Earl of Browne in the Jacobite peerage. His wife, Countess Marie Philippine von Martinitz, has valuable connections at court and his sister, Barbara (b. Limerick 1700), is married to Freiherr Francis Patrick O’Neillan, a Major General in the Austrian Service. So, by the age of 29 Browne is already colonel of an Austrian infantry regiment.

Browne justifies his early promotion in the field, and in the Italian campaign of 1734 he greatly distinguishes himself. In the Tirolese fighting of 1735, and in the Turkish war, he wins further distinction as a general officer.

Browne is a lieutenant field marshal in command of the Silesian garrisons when in 1740 Frederick II and the Prussian army overruns the province. His careful employment of such resources as he possesses materially hinders the king in his conquest and allows time for Austria to collect a field army. He is present at Mollwitz, where he receives a severe wound. His vehement opposition to all half-hearted measures brings him frequently into conflict with his superiors but contributes materially to the unusual energy displayed by the Austrian armies in 1742 and 1743.

In the following campaigns Browne exhibits the same qualities of generalship and the same impatience of control. In 1745 he serves under Count Traun and is promoted to the rank of Feldzeugmeister. In 1746 he is present in the Italian campaign and the battles of Piacenza and Rottofreddo. He and an advanced guard force their way across the Apennine Mountains and enter Genoa. He is thereafter placed in command of the invasion of France mounted in winter 1746-47, leading to the Siege of Antibes, but he is obliged to break off the invasion and return to Italy in February 1747 after Genoa rises in rebellion against the Austrian garrison he had left behind. In early 1747 he is appointed commander of all imperial forces in Italy, replacing Antoniotto Botta Adorno. At the end of the war, he is engaged in the negotiations on troop withdrawals from Italy, which leads to the convention of Nice on January 21, 1749. He becomes commander-in-chief in Bohemia in 1751, and field marshal two years later.

Browne is still in Bohemia when the Seven Years’ War opens with Frederick’s invasion of Saxony in 1756. His army, advancing to the relief of Pirna, is met, and, after a hard struggle, defeated by the king at the Battle of Lobositz, but he draws off in excellent order, and soon makes another attempt with a picked force to reach Pirna, by wild mountain tracks. He never spares himself, bivouacking in the snow with his men, and Thomas Carlyle records that private soldiers made rough shelters over him as he slept.

Brown actually reaches the Elbe at Bad Schandau, but as the Saxons are unable to break out, he retires, having succeeded, however, in delaying the development of Frederick’s operations for a whole campaign. In the campaign of 1757, he voluntarily serves under Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine who is made commander-in-chief. On May 6 of that year, while leading a bayonet charge at the Battle of Prague, Browne, like Kurt Christoph, Graf von Schwerin, on the same day, meets his death. He is carried mortally wounded into Prague, and there dies on June 26, 1757.