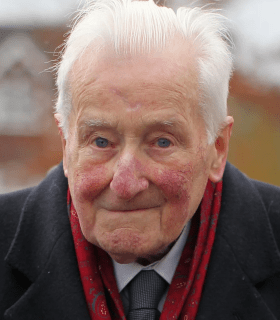

William McMillen, Irish republican activist and an officer of the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) from Belfast, Northern Ireland, is killed during a feud with the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA) on April 28, 1975.

McMillen is born in Belfast on May 19, 1927, and joins the Irish Republican Army (IRA) at age 16 in 1943. During the IRA’s border campaign (1956–62), he is interned and held in Crumlin Road Gaol. In 1964, he runs in the British general election as an Independent Republican candidate. When he places the Irish tricolour in the window of his election office in the lower Falls Road area, this sparks a riot between republicans, loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). There have been tensions on the issue since the government of Northern Ireland banned the flying of the tricolour under the Flags and Emblems (Display) Act (Northern Ireland) 1954.

In October 1964, during the general election campaign, a photo of McMillen is placed in the window of the election office in Divis Street flanked on one side by the Starry Plough flag and on the other by the tricolour. His campaign draws national attention after Ian Paisley demands that police remove the tricolour from McMillen’s election offices. The RUC raids the premises and confiscates the flag, sparking several days of rioting during which McMillen leads several thousand protesters in defiantly displaying the tricolour. He recalls the IRA gaining a “couple of dozen recruits” following the election, but he finishes at the bottom of the poll with 3,256 votes (6%). Around this time, he succeeds Billy McKee as the Officer commanding (OC) of the Belfast Brigade.

McMillen is keen to work for the unity of Protestant and Catholic workers. Roy Garland recalls that McMillan’s grandfather was master of an Orange lodge in Edinburgh and McMillan knew of that heritage and the meaning of the colours of the Irish flag. He prominently displays in his election offices a verse of a poem by John Frazier, a Presbyterian from County Offaly: “Till then the Orange lily be your badge my patriot brother. The everlasting green for me and we for one and other.”

In 1967, McMillen is involved in the formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) and is a member of a three-man committee which draws up the Association’s constitution. The NICRA’s peaceful activities result in violent opposition from many unionists, leading to fears that Catholic areas will come under attack. In May 1969, when asked at an IRA army council meeting by Ruairí Ó Brádaigh how many weapons the Belfast Brigade has for defensive operations, McMillen states they have only one pistol, a machine gun and some ammunition.

By August 14, 1969, serious rioting has broken out in Belfast and Catholic districts come under attack from both civilian unionists and the RUC. McMillen’s IRA command by this point still has only a limited number of weapons because the leadership in Dublin are reluctant to release guns. While he is involved in some armed actions on this day, he is widely blamed by those who established the Provisional IRA for the IRA’s failure to adequately defend Catholic neighbourhoods from Ulster loyalist attack. He is arrested and temporarily detained by the RUC on the morning of August 15 but is released shortly afterward.

McMillen’s role in the 1969 riots is very important within IRA circles, as it is one of the major factors contributing to the split in the movement in late 1969. In a June 1972 lecture organised by Official Sinn Féin in Dublin, he defends his conduct, stating that by 1969 the total membership of the Belfast IRA is approximately 120 men, and their armaments have increased to a grand total of 24 weapons, most of which are short-range pistols.

In September, McMillen calls a meeting of IRA commanders in Belfast. Billy McKee and several other republicans arrive at the meeting armed and demand McMillen’s resignation. He refuses, but many of those unhappy with his leadership break away and refuse to take orders from him or the Dublin IRA leadership. Most of them join the Provisional Irish Republican Army, when this group splits off from the IRA in December 1969. McMillen himself remains loyal to the IRA’s Dublin leadership, which becomes known as the Official IRA. The split rapidly develops into a bitter rivalry between the two groups. In April 1970, he is shot and wounded by Provisional IRA members in the Lower Falls area of Belfast.

In June 1970, McMillen’s Official IRA have their first major confrontation with the British Army, which had been deployed to Belfast in the previous year, in an incident known as the Falls Curfew. The British Army mounts an arms search in the Official IRA stronghold of the Lower Falls, where they are attacked with a grenade by Provisional IRA members. In response, the British flood the area with troops and declare a curfew. This leads to a three-day gun battle between 80 to 90 Official IRA members led by McMillen and up to 3,000 British troops. Five civilians are killed in the fighting and about 60 are wounded. In addition, 35 rifles, 6 machine guns, 14 shotguns, grenades, explosives and 21,000 rounds of ammunition, all belonging to the OIRA, are seized. McMillen blames the Provisionals for instigating the incident and then refusing to help the Officials against the British.

This ill-feeling eventually leads to an all-out feud between the republican factions in Belfast in March 1971. The Provisionals attempt to kill McMillen again, as well as his second-in-command, Jim Sullivan. In retaliation, McMillen has Charlie Hughes, a young PIRA member, killed. Tom Cahill, brother of leading Provisional Joe Cahill, is also shot and wounded. After these deaths, the two IRA factions in Belfast negotiate a ceasefire and direct their attention instead at the British Army.

When the Northern Ireland authorities introduce internment in August 1971, McMillen flees Belfast for Dundalk in the Republic of Ireland, where he remains for several months. During this time, the Official IRA carries out many attacks on the British Army and other targets in Northern Ireland. However, in April 1972, the organisation in Belfast is badly weakened by the death of their commander in the Markets area, Joe McCann. In May of that year, the Dublin leadership of the OIRA calls a ceasefire, a move which McMillen supports. Nevertheless, in the year after the ceasefire, his command kills seven British soldiers in what they term “retaliatory attacks.” McMillen serves on the Ard Chomhairle (leadership council) of Official Sinn Féin.

By 1974, a group of OIRA members around Seamus Costello are unhappy with the ceasefire. In December 1974, they break away from the Official movement, forming the Irish Republican Socialist Party (IRSP) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). Some OIRA members under McMillen’s command, including the entire Divis Flats unit, defect to the new grouping. This provokes another intra-republican feud in Belfast. The feud begins with arms raids on OIRA dumps and beatings of their members by the INLA. McMillen, in response is accused of drawing up a “death list” of IRSP/INLA members and even of handing information on them over to the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

The first killing comes on February 20, 1975, when the OIRA shoot dead an INLA member named Hugh Ferguson in west Belfast. A spate of shootings follows on both sides.

On April 28, 1975, McMillen is shot dead by INLA member Gerard Steenson, as he is shopping in a hardware shop on Spinner Street with his wife Mary. He is hit in the neck and dies at the scene. His killing is unauthorised and is condemned by INLA/IRSP leader Seamus Costello. Despite this, the OIRA tries to kill Costello on May 9, 1975, and eventually kills him two years later. McMillen’s death is a major blow to the OIRA in Belfast.