Brian Keenan, a member of the Army Council of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), dies on May 21, 2008, at Cullyhanna, County Armagh, Northern Ireland, following a battle with colorectal cancer. He receives an 18-year prison sentence in 1980 for conspiring to cause explosions and plays a key role in the Northern Ireland peace process.

The son of a member of the Royal Air Force (RAF), Keenan is born on July 17, 1941, in Swatragh, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, before his family moves to Belfast. As a teenager, he moves to England to find work, for a time working as a television repairman in partnership with his brother in Corby, Northamptonshire. During this time, he comes to the attention of the police when he damages a cigarette machine, which leads to police having his fingerprints on file. He returns to Northern Ireland when the Troubles begin and starts working at the Grundig factory in the Finaghy area of Belfast where he acquires a reputation as a radical due to his involvement in factory trade union activities.

Despite his family having no history of republicanism, Keenan joins the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1970 or 1971, and by August 1971 is the quartermaster of the Belfast Brigade. He is an active IRA member, planning bombings in Belfast and travelling abroad to make political contacts and arrange arms smuggling, acquiring contacts in East Germany, Libya, Lebanon and Syria. In 1972, he travels to Tripoli to meet with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in order to acquire arms and finance from his government. In early 1973 he takes over responsibility for control of the IRA’s bombing campaign in England and also becomes IRA Quartermaster General. In late 1973, he is the linchpin of the kidnap of his former employer at Grundig, director Thomas Niedermayer.

In early 1974, Keenan plans to break Gerry Adams and Ivor Bell out of Long Kesh using a helicopter, in a method similar to Seamus Twomey‘s escape from Mountjoy Prison in October 1973, but the plan is vetoed by Billy McKee. He is arrested in the Republic of Ireland in mid-1974 and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment for IRA membership. On March 17, 1975, he is shot and wounded while attempting to lead a mass escape from Portlaoise Prison. While being held in Long Kesh, Gerry Adams helps to devise a blueprint for the reorganisation of the IRA, which includes the use of covert cells and the establishment of a Southern Command and Northern Command. As the architects of the blueprint, Adams, Bell and Brendan Hughes, are still imprisoned, Martin McGuinness and Keenan tour the country trying to convince the IRA Army Council and middle leadership of the benefits of the restructuring plan, with one IRA member remarking “Keenan was a roving ambassador for Adams.” The proposal is accepted after Keenan wins support from the South Derry Brigade, East Tyrone Brigade and South Armagh Brigade, with one IRA member saying, “Keenan was really the John the Baptist to Adams’ Christ.”

In December 1975, members of an IRA unit based in London are arrested following the six-day Balcombe Street siege. The IRA unit had been active in England since late 1974 carrying out a series of bombings, and a few months after his release from prison Keenan visits the unit in Crouch Hill, London, to give it further instructions. In follow-up raids after the siege, police discover crossword puzzles in his handwriting and his fingerprints on a list of bomb parts. A warrant is issued for his arrest.

Garda Síochána informer Sean O’Callaghan claims that Keenan recommended IRA Chief of Staff Seamus Twomey to authorise an attack on Ulster Protestants in retaliation to an increase in sectarian attacks on Catholic civilians by Protestant loyalist paramilitaries, such as the killing of three Catholics in a gun and bomb attack by the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) on Donnelly’s Bar in Silverbridge, County Armagh on December 19, 1975. According to O’Callaghan “Keenan believed that the only way, in his words, to put the nonsense out of the Prods [Protestants] was to just hit back much harder and more savagely than them.” Soon after the sectarian Kingsmill massacre occurs, when ten Protestant men returning home from their work are ordered out of a minibus they are travelling in and executed en masse with a machine gun on January 5, 1976.

Keenan is arrested on the basis of the 1975 warrant near Banbridge on March 20, 1979, when the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) stopped two cars travelling north on the main road from Dublin to Belfast and is extradited to England to face charges relating to the Balcombe Street Gang‘s campaign in England. His capture is a blow to the IRA, in particular as he was carrying an address book listing his contacts including Palestinian activists in the United Kingdom. The IRA responds by dispatching Bobby Storey and three other members to break Keenan out of prison using a helicopter, but all four are arrested and remanded to Brixton Prison. Keenan stands trial at the Old Bailey in London in June 1980 defended by Michael Mansfield and is accused of organising the IRA’s bombings in England and being implicated in the deaths of eight people including Ross McWhirter and Gordon Hamilton Fairley. He is sentenced to eighteen years imprisonment after being found guilty on June 25, 1980.

Keenan continues to support Gerry Adams while in prison. In August 1982 Adams is granted permission by the IRA’s Army Council to stand in a forthcoming election to the Northern Ireland Assembly, having been refused permission at a meeting the previous month. In a letter sent from Leicester Prison, Keenan writes that he “emphatically” supports the move and endorses the Army Council’s decision.

Keenan is released from prison in June 1993 and by 1996 is one of seven members of the IRA’s Army Council. Following the events after the IRA’s ceasefire of August 1994, he is openly critical of Gerry Adams and the “tactical use of armed struggle,” or TUAS, strategy employed by the republican movement. After the Northern Ireland peace process becomes deadlocked over the issue of the IRA decommissiong its arms, he and the other members of the Army Council authorise the Docklands bombing which kills two people and marks the end of the IRA’s eighteen-month ceasefire in February 1996.

Keenan outlines the IRA’s public position in May 1996 at a ceremony in memory of hunger striker Seán McCaughey at Milltown Cemetery, where he states, “The IRA will not be defeated…Republicans will have our victory…Do not be confused about decommissioning. The only thing the Republican movement will accept is the decommissioning of the British state in this country.” In the same speech he accuses the British of “double-dealing” and denounces the Irish government as “spineless.”

On February 25, 2001, Keenan addresses a republican rally in Creggan, County Armagh, saying that republicans should not fear “this phase” of “the revolution” collapsing should the Good Friday Agreement fail. He confirms his continued commitment to the Armalite and ballot box strategy, saying that both political negotiations and violence are “legitimate forms of revolution” and that both “have to be prosecuted to the utmost.” He goes on to say, “The revolution can never be over until we have British imperialism where it belongs—in the dustbin of history,” a message aimed at preventing rank-and-file IRA activists defecting to the dissident Real IRA.

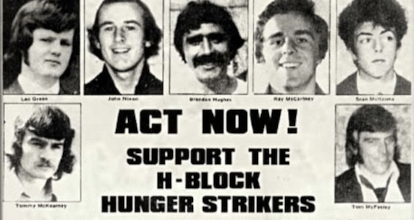

Keenan plays a key role in the peace process, acting as the IRA’s go-between with the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD). Gerry Adams remarks, “There wouldn’t be a peace process if it wasn’t for Brian Keenan.” Keenan resigns from his position on the Army Council in 2005 due to ill-health, and is replaced by Bernard Fox, who had taken part in the 1981 Irish hunger strike. On May 6, 2007, he is guest speaker at a rally in Cappagh, County Tyrone, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the deaths of the so-called “Loughgall Martyrs,” eight members of the IRA East Tyrone Brigade killed by the Special Air Service (SAS) in 1987.

In July 2002, Keenan is diagnosed as suffering from terminal colorectal cancer. It is alleged by the Irish Independent and The Daily Telegraph that Keenan succeeded Thomas “Slab” Murphy as Chief of Staff of the Provisional IRA at some point between the late 1990s and the mid-2000s before he relinquished the role to deal with his poor health caused by cancer.

Keenan’s last years are spent living with his wife in Cullyhanna, County Armagh, where he dies of cancer on May 21, 2008. He is an atheist and receives a secular funeral, representing a major republican show of strength.