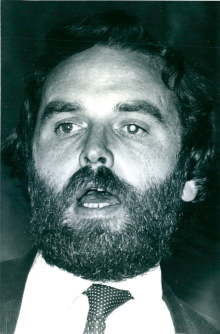

Hugh Anthony Logue, former Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician and economist who now works as a commentator on political and economic issues, is born on January 23, 1949, in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. He is also a director of two renewable energy companies in Europe and the United States. He is the father of author Antonia Logue.

Logue grows up outside the village of Claudy in County Londonderry, the eldest of nine children born to Denis Logue, a bricklayer, and Kathleen (née Devine). He gains a scholarship to St. Columb’s College which he attends from 1961 to 1967. In 1967, he commences at St. Joseph’s Teacher Training college (Queen’s University) in Belfast from which he qualifies as a teacher of Mathematics in 1970. He first comes to prominence as a member of the executive of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the only SDLP member of the executive. He stands as a candidate in elections to the new Northern Ireland Assembly in 1973 and is elected for Londonderry, at the age of 24, the youngest candidate elected that year. With John Hume and Ivan Cooper, he is arrested by the British Army during a peaceful demonstration in Londonderry in August 1971. Their conviction is ultimately overturned by the Law Lords R. (Hume) v Londonderry Justices (972, N.I.91) requiring the then British Government to introduce retrospective legislation to render legal previous British Army actions in Northern Ireland.

The Northern Ireland State Papers of 1980 show that together with John Hume and Austin Currie, Logue plays a key role in presenting the SDLP’S ‘Three Strands’ approach to the Thatcher Government’s Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Humphrey Atkins in April 1980. The “Three Strands” approach eventually becomes the basis for the Good Friday Agreement. The Irish State papers from 1980 reveal that he is a confidante of the Irish Government of that time, briefing it regularly on the SDLP’s outlook.

Logue is also known for his controversial comments at Trinity College Dublin at the time of the power-sharing Sunningdale Agreement, which many blame for helping to contribute to the Agreement’s defeat, to wit, that: [Sunningdale was] “the vehicle that would trundle Unionists into a united Ireland.” The next line of the controversial speech says, “the speed the vehicle moved at was dependent on the Unionist community.” In an article in The Irish Times in 1997 he claims that this implies that unity is always based on consent and acknowledged by Unionist Spokesman John Laird in the NI Assembly in 1973.

Logue unsuccessfully contests the Londonderry seat in the February 1974 and 1979 Westminster Elections. He is elected to the 1975 Northern Ireland Constitutional Convention and the 1982 Northern Ireland Assembly. He is a member of the New Ireland Forum in 1983. In the 1980s he is a member of the Irish Commission for Justice and Peace and plays a prominent part in its efforts to resolve the 1981 Irish hunger strike. His role is credited in Ten Men Dead: The Story of the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike by David Beresford, Biting the Grave by P. O’Malley and, more recently, in Blanketmen: An Untold Story of the H-block Hunger Strike (New Island Books, 2016) and Afterlives: The Hunger Strike and the Secret Offer that Changed Irish History (Lilliput Press, 2011) by former Provisional Irish Republican Army volunteer Richard O’Rawe. Following the New Ireland Forum in 1984 and John Hume’s decision to represent the redrawn Londonderry constituency as Foyle and a safe seat, Logue leaves the Dublin-based, National Board for Science and Technology and joins the European Commission in 1984 in Brussels.

Following the 1994 Irish Republican Army (IRA) ceasefire, Logue, along with two EU colleagues, is asked by EU President Jacques Delors to consult widely throughout Northern Ireland and the Border regions and prepare recommendations for a Peace and Reconciliation Fund to underpin the peace process. Their community-based approach becomes the blueprint for the Peace Programme. In 1997, then EU President Jacques Santer asks the team, led by Logue, to return to review the programme and advise for a renewed Peace II programme. Papers published by National University Galway in 2016 from Logue’s archives indicate that he is the originator of the Peace Fund concept within the European Commission.

At the European Commission from 1984 to 1998, Logue creates Science and Technology for Regional Innovation and Development in Europe (STRIDE). In 1992, he is joint author with Giovanni de Gaetano, of RTD potential in the Mezzogiorno of Italy: the role of science parks in a European perspective and, with A. Zabaniotou and University of Thessaloniki, Structural Support For RTD.

Further publications by Logue follow: Research and Rural Regions (1996) and RTD potential in the Objective 1 regions (1997). With the fall of the Berlin Wall, his attention turns to Eastern Europe and in March 1998 publishes a set of studies Impact of the enlargement of the European Union towards central central and Eastern European countries on RTD- Innovation and Structural policies.

Logue convenes the first EU seminar on “Women in Science” in 1993 and jointly publishes with LM Telapessy Women in Scientific and Technological Research in the European Community, highlighting the barriers to women’s advancement in the Research world.

As the former vice-chairman of the North Derry Civil Rights Association, Logue gives evidence at the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday. He is special adviser to the Office of First and Deputy First Minister from 1998 to 2002 and as an official of the European Commission. In 2002–03, he is a fellow of the Institute for British – Irish Studies at University College Dublin (UCD). In July 2006, he is appointed as a board member of the Irish Peace Institute, based at the University of Limerick and in 2009 is appointed Vice Chairman. He is a Life Member of the Institute of International and European Affairs.

On December 17, 2007, Logue is appointed as a director to InterTradeIreland (ITI), the North-South Body established under the Good Friday Agreement to promote economic development in Ireland. There he chairs the ITI’s Fusion programme, bringing north–south industrial development in Innovation and Research. Integrating Ireland economically is a theme of his writing throughout his career, most recently in The Irish Times and in earlier publications as economic spokesman for the SDLP. He is economist at the Dublin-based National Board for Science and Technology from 1981 to 1984.

Logue, after leaving the European Commission in 2005, becomes involved in Renewable Energy and is chairman of Priority Resources as well as a director of two companies, one in solar energy, the other in wind energy. In November 2011, he is elected to the main board of European Association of Energy (EAE).

In November 2023, Logue is awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Galway in recognition of “a lifetime dedicated to civil rights, human rights, equality and peace in Northern Ireland, Ireland and Europe.” He donates an archive of material, more than 20 boxes of manuscripts, documents, photographs and political ephemera, on the development of the SDLP from the early 1970s to the University of Galway.