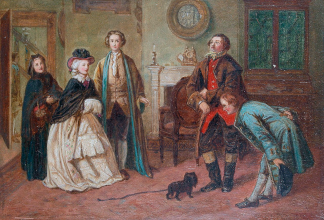

The Good-Natur’d Man, a play written by Oliver Goldsmith in 1768, is first performed at Central London’s Covent Garden on January 29, 1768. The play is written in the form of a comedy with Mary Bulkley as Miss Richland. It is released at the same time as Hugh Kelly‘s False Delicacy, staged at Drury Lane Theatre. The two plays go head-to-head, with Kelly’s proving the more popular. Goldsmith’s play is a middling success, and the printed version of the play becomes popular with the reading public.

Although his birth date and year and birthplace are not known with any certainty, it is believed that Goldsmith is born on November 10, 1728, in Kilkenny West, County Westmeath. He is an Anglo-Irish essayist, poet, novelist, dramatist, and eccentric, made famous by such works as the series of essays The Citizen of the World, or, Letters from a Chinese Philosopher (1762), the poem The Deserted Village (1770), the novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), and the play She Stoops to Conquer (1773).

Goldsmith is the son of an Anglo-Irish clergyman, the Rev. Charles Goldsmith, curate in charge of Kilkenny West. At about the time of his birth, the family moves into a substantial house at nearby Lissoy, where he spends his childhood. Much has been recorded concerning his youth, his unhappy years as an undergraduate at Trinity College Dublin, where he received the BA degree in February 1749, and his many misadventures before he leaves Ireland in the autumn of 1752 to study in the medical school at Edinburgh. By this time his father has died, but several of his relations support him in his pursuit of a medical degree. Later on, in London, he comes to be known as Dr. Goldsmith, Doctor being the courtesy title for one who holds the Bachelor of Medicine, but he takes no degree while at Edinburgh nor, so far as anyone knows, during the two-year period when, despite his meagre funds, which are eventually exhausted, he somehow manages to make his way through Europe. The first period of his life ends with his arrival in London, bedraggled and penniless, early in 1756.

Goldsmith’s rise from total obscurity is a matter of only a few years. He works as an apothecary‘s assistant, school usher, physician, and as a hack writer, reviewing, translating, and compiling. Much of his work is for Ralph Griffiths‘s Monthly Review. It remains amazing that this young Irish vagabond, unknown, uncouth, unlearned, and unreliable, is yet able within a few years to climb from obscurity to mix with aristocrats and the intellectual elite of London. Such a rise is possible because he has one quality, soon noticed by booksellers and the public, that his fellow literary hacks do not possess – the gift of a graceful, lively, and readable style.

Goldsmith’s rise begins with the Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning in Europe (1759), a minor work. Soon he emerges as an essayist, in The Bee and other periodicals, and above all in his Chinese Letters. These essays are first published in the journal The Public Ledger and are collected as The Citizen of the World in 1762. The same year brings his The Life of Richard Nash. Already he is acquiring those distinguished and often helpful friends whom he alternately annoys and amuses, shocks and charms – Samuel Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Percy, David Garrick, Edmund Burke, and James Boswell.

The obscure drudge of 1759 becomes in 1764 one of the nine founder-members of the famous The Club, a select body, including Reynolds, Johnson, and Burke, which meets weekly for supper and talk. Goldsmith can now afford to live more comfortably, but his extravagance continually runs him into debt, and he is forced to undertake more hack work. He thus produces histories of England and of ancient Rome and Greece, biographies, verse anthologies, translations, and works of popular science.

Goldsmith’s premature death on April 4, 1774, may be partly due to his own misdiagnosis of a kidney infection. He is buried in Temple Church in London. A monument is originally raised to him at the site of his burial, but this is destroyed in an air raid in 1941. A monument to him survives in the centre of Ballymahon, also in Westminster Abbey with an epitaph written by Samuel Johnson.

Among Goldsmith’s papers is found the prospectus of an encyclopedia, to be called the Universal dictionary of the arts and sciences. He wishes this to be the British equivalent of the Encyclopédie and it is to include comprehensive articles by Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Sir William Jones, Charles James Fox and Dr. Charles Burney. The project, however, is not realised due to Goldsmith’s death.

(Pictured: “Mr Honeywell introduces the bailiffs to Miss Richland as his friends,”a scene from the play “The Good-Natur’d Man” by Oliver Goldsmith, oil on panel by William Powell Frith)