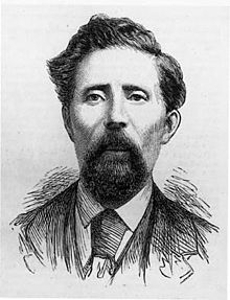

James Carey, a Fenian and informer most notable for his involvement in the Phoenix Park Murders, is shot and killed by Patrick O’Donnell aboard the Melrose on July 29, 1883.

Carey is born in James Street, Dublin, in 1845. He becomes a bricklayer and builder as well as the leading spokesman of his trade and obtains several large building contracts. During this period Carey is engaged in an Irish nationalist conspiracy, but to outward appearance he is one of the rising men of Dublin. He is involved in religious and other societies, and at one time is spoken of as a possible lord mayor. In 1882 he is elected a town councillor.

About 1861 Carey joins the Irish Republican Brotherhood, soon becoming treasurer. In 1881 he breaks with the IRB and forms a new group which assumes the title of the Irish National Invincibles and establishes their headquarters in Dublin. Carey takes an oath as one of the leaders. The object of the Invincibles is to remove all “tyrants” from the country.

The secret head of the Invincibles, known as No. 1, gives orders to kill Thomas Henry Burke, the under-secretary to the lord-lieutenant. On May 6, 1882, nine of the conspirators proceed to the Phoenix Park where Carey, while sitting on a jaunting-car, points out Burke to the others. At once they attack and kill him with knives and, at the same time, also kill Lord Frederick Cavendish, the newly appointed chief secretary, who happens to be walking with Burke.

For a long time no clue can be found to identify the perpetrators of the act. However, on January 13, 1883, Carey is arrested and, along with sixteen other people, charged with a conspiracy to murder public officials. On February 13, Carey turns queen’s evidence, betraying the complete details of the Invincibles and of the murders in the Phoenix Park. His evidence, along with that of getaway driver Michael Kavanagh, results in the execution of five of his associates by hanging.

His life being in great danger, he is secretly put onboard the Kinfauns Castle with his wife and family, which sails for the Cape on July 6. Carey travels under the name of Power. Aboard the same ship is Patrick O’Donnell, a bricklayer. Not knowing his true identity, O’Donnell becomes friendly with Carey. After stopping off in Cape Town, he is informed by chance of Carey’s real identity. He continues with Carey on board the Melrose for the voyage from Cape Town to Natal. On July 29, 1883, when the vessel is twelve miles off Cape Vaccas, O’Donnell uses a pistol he has in his luggage to shoot Carey dead.

O’Donnell is brought to England and is tried for murder. After being found guilty, he is executed on December 17 at Newgate.