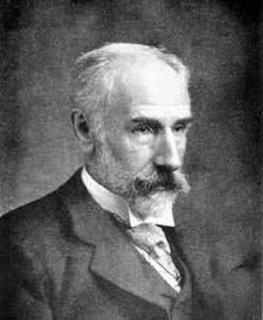

Francis Ysidro Edgeworth, Anglo-Irish philosopher and political economist who makes significant contributions to the methods of statistics during the 1880s, dies in Oxford, Oxfordshire, England on February 13, 1926.

Edgeworth is born on February 8, 1845, at Edgeworthstown, County Longford, the fifth of six sons of Francis Beaufort Edgeworth and his Spanish wife Rosa Florentina Eroles, daughter of exiled Catalan general Antonio Eroles. He is a grandson of Richard Lovell Edgeworth. His father dies when he is two years old, followed by his aunt Maria Edgeworth two years later. He is educated at home by tutors until he enters Trinity College Dublin (TCD) at the age of seventeen. Leaving to become a scholar at Magdalen Hall, he then proceeds to Balliol College, Oxford, where he takes a first-class degree in literae humaniores. After studying law at the Inner Temple, he is called to the bar in 1877, but never practises, choosing instead to lecture in logic at King’s College, London, where in 1888 he is appointed Professor of Political Economy, and in 1890 Tooke Professor of Economic Science and Statistics.

In 1891, Edgeworth becomes Drummond Professor of Political Economy at Oxford and is elected a fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, where he resides principally for the remainder of his career. In the same year he is appointed the founding editor of The Economic Journal and is credited with its success by the economist (and later joint editor) John Maynard Keynes. He writes seven small books and numerous articles and reviews but does not develop a systematic approach to economics. Thus, he never produces a treatise, once informing Keynes that it is for the same reason he never married – large-scale enterprises do not appeal to him. Instead, he applies a highly abstract, mathematical approach to economics, a methodology that is not helped by a difficult writing style. Although his work is sometimes controversial, he makes many original contributions to economics and statistics, which are still recognised. For example, in his own lifetime he is the finest exponent of what he himself calls “mathematical psychics,” the application of quasi-mathematical methods to the social sciences. His career, however, never quite fulfills its promise.

In 1911, Edgeworth inherits the Edgeworthstown estate, and shortly afterward becomes president of the Royal Economic Society (1912–14) and Fellow of the British Academy. Ahead of his time in many areas, he argues against the inequality of men’s and women’s wages. He has an eccentric character and is, according to Keynes, a difficult mixture of reserve, pride, kindness, modesty, courtesy, and stubbornness. His friend and fellow economist Alfred Marshall once says, “Francis is a charming fellow, but you must be careful with Ysidro.” He is never particularly happy, and dies a bachelor, although Keynes admits that it is not from want of susceptibility to women.

Edgeworth resigns his chair in 1922 and is appointed emeritus professor. In 1925, his essays are published in three volumes as his Collected Economic Papers, and for the first time his reputation is properly established throughout the world. He dies at Oxford on February 13, 1926.

(From: “Edgeworth, Francis Ysidro” by Patrick M. Geoghegan, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)