The Battle of the Diamond, a planned confrontation between the Catholic Defenders and the Protestant Peep o’ Day Boys, takes place on September 21, 1795, near Loughgall, County Armagh. The Diamond, which is a predominantly Protestant area, is a minor crossroads in County Armagh, lying almost halfway between Loughgall and Portadown.

In the 1780s, County Armagh is the most populous county in Ireland, and the center of its linen industry. Its population is equally split between Protestants, who dominate in the northern part of the county, and Catholics, who dominate in the south. Sectarian tensions increase throughout the decade and are exacerbated by the relaxing of some of the Penal Laws, failure to enforce others, and the entry of Catholics into the linen industry at a time when land is scarce, and wages are decreasing due to pressure from the mechanised cotton industry.

By 1784, sectarian fighting breaks out between gangs of Protestants and Catholics. The Protestants re-organise themselves as the Peep o’ Day Boys, with the Catholics forming the Defenders. The next decade sees an escalation in the violence between the two and the local population as homes are raided and wrecked.

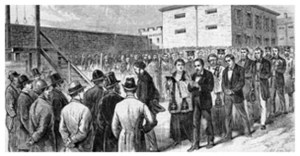

On the morning of September 21, the Defenders, numbering around 300, make their way downhill from their base, occupying Daniel Winter’s homestead, which lay to the northwest of The Diamond and directly in their line of advance. News of the advance reaches the Peep o’ Day Boys who quickly form at the brow of the hill where they have made their camp. From this position, they gain three crucial advantages: the ability to comfortably rest their muskets allowing for more accurate shooting, a steep uphill location which makes it hard for attackers to scale, and a direct line-of-sight to Winter’s cottage, which the Defenders have made their rallying point.

The shooting begins and, after Captain Joseph Atkinson gives his weapon and powder to the Peep o’ Day Boys, he rides to Charlemont Garrison for troops to quell the trouble. There is no effective unit stationed in the garrison at the time, despite the fact a detachment of the North-Mayo Militia is stationed in Dungannon and a detachment of the Queen’s County Militia is at Portadown.

The battle is short, and the Defenders suffer “not less than thirty” fatalities. James Verner, whose account of the battle is based on hearsay, gives the total as being nearly thirty, while other reports give the figure as being forty-eight, however this may be taking into account those that die afterwards from their wounds. A large number of Defenders are also claimed to have been wounded. One of those claimed to have been killed is “McGarry of Whiterock,” the leader of the Defenders. The Peep o’ Day Boys on the other hand, in the safety of the well-defended hilltop position, suffered no casualties.

In the aftermath of the battle, the Peep o’ Day Boys retire to James Sloan’s inn in Loughgall, and it is here that James Wilson, Dan Winter, and James Sloan found the Orange Order, a defensive association pledged to defend “the King and his heirs so long as he or they support the Protestant Ascendancy.” The first Orange lodge of this new organisation is established in Dyan, County Tyrone, founding place of the Orange Boys.

(Pictured: Daniel Winter’s home near Loughgall)