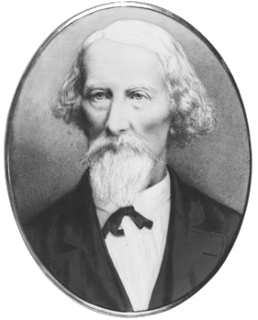

Maolra Seoighe (English: Myles Joyce), is an Irish man who is wrongfully convicted and hanged on December 15, 1882. He is found guilty of the Maumtrasna Murders and is sentenced to death. Though he can only speak Irish, the case is heard in English without any translation service. He is posthumously pardoned in 2018.

Seoighe is the most prominent figure in a controversial trial in 1882 that takes place while Ireland is part of the United Kingdom. Three Irish language speakers are condemned to death for the murder of a local family (John Joyce, his wife Brighid, his mother Mairéad, his daughter Peigí and son Mícheál) in Maumtrasna, on the border between County Mayo and County Galway. It is presumed by the authorities to be a local feud connected to sheep rustling and the Land War. Eight men are convicted on what turns out to be perjured evidence and three of them condemned to death: Maolra Seoighe (a father of five children), Pat Casey and Pat Joyce.

Covering the incident, The Spectator writes the following:

“The Tragedy at Maumtrasna, investigated this week in Dublin, almost unique as it is in the annals of the United Kingdom, brings out in strong relief two facts which Englishmen are too apt to forget. One is the existence in particular districts of Ireland of a class of peasants who are scarcely civilised beings, and approach far nearer to savages than any other white men; and the other is their extraordinary and exceptional gloominess of temper. In remote places of Ireland, especially in Connaught, on a few of the islands, and in one or two mountain districts, dwell cultivators who are in knowledge, in habits, and in the discipline of life no higher than Maories or other Polynesians.”

The court proceedings are carried out in a language the accused do not understand (English), with a solicitor from Trinity College Dublin (TCD), who does not speak Irish. The three are executed in Galway by William Marwood for the crime in 1882. The role of John Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer, who is then Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, is the most controversial aspect of the trial, leading most modern scholars to characterise it as a miscarriage of justice. Research carried out in The National Archives by Seán Ó Cuirreáin, has found that Spencer “compensated” three alleged eyewitnesses to the sum of £1,250, equivalent to €157,000 (by 2016 rates).

As of 2016, nobody has issued an apology or pardon for the executions, though the case has been periodically taken up by various political figures. The then MP for Westmeath, Timothy Harrington, takes up the case, claiming that the Crown Prosecutor for the case George Bolton, had deliberately withheld evidence from the trial. In 2011, two sitting members of the House of Lords, the Liberal Democrat life peers David Alton and Eric Lubbock, request a review of the case. Crispin Blunt, Tory Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Prisons and Youth Justice, states that Seoighe was “probably an innocent man,” but he does not seek an official pardon.

Seoighe’s final words are: “Feicfidh mé Iosa Críost ar ball beag – crochadh eisean san éagóir chomh maith. … Ara, tá mé ag imeacht … Go bhfóire Dia ar mo bhean agus a cúigear dílleachtaí.” (I will be seeing Jesus Christ soon – he too was also unjustly hanged … I am leaving … the blessings of God on my wife and her five orphans.)

On April 4, 2018, Michael D. Higgins, the President of Ireland, issues a pardon on the advice of the government of Ireland saying “Maolra Seoighe was wrongly convicted of murder and was hanged for a crime that he did not commit”. It is the first presidential pardon relating to an event predating the foundation of the state in 1922 and the second time a pardon has been issued after an execution. Seoighe’s case is not an isolated one, and there are strong similarities with the case of Patrick Walsh who was hanged in the Galway jail on September 22, 1882, just three months before Seoighe for the murders of Martin and John Lydon. The same key players and political factors are active in both cases and his conviction is just as questionable as that of Seoighe.

In September 2009, the story is featured on RTÉ‘s CSI programme under an episode entitled CSI Maamtrasna Massacre. A dramatised Irish language film regarding the affair, entitled Murdair Mhám Trasna, produced by Ciarán Ó Cofaigh is released in 2017.