The Irish Free State is admitted into the League of Nations on September 10, 1923.

The Irish Free State is admitted into the League of Nations on September 10, 1923.

In 1922, Éamon de Valera speaks at a League of Nations meeting and is critical of Article 10 of the League Covenant which preserves the existing of territorial integrity of member states. This article prevents Ireland from gaining membership in the League of Nations, because it is a territory of the United Kingdom, who is a member state. However, it does not clarify what rights dominion states have and if they can have their own seat. This means that when the Constitution of the Irish Free State goes into effect, the Irish government does not know what type of role it can play in the League of Nations and if, at that point, it is possible to become a member. The League of Nations final decision is that Ireland can not become a member until it’s constitution is officially enacted and it officially becomes a free state.

The Constitution of the Irish Free State is enacted on December 6, 1922, and is recognized as an official international instrument. This allows Ireland to submit an application for entry into the League of Nations.

The applications process goes smoothly until the spring of 1923 when the Seanad Éireann, the upper house of the Oireachtas, complains that only Dáil Éireann, the lower house, has approved the application. A previous decision has made the application an Executive Council decision, and under the Provisional Government, the Seanad has approved the application process. With this approval, the Executive Council continues the application process, however, the new Seanad is upset about their lack of input. This problem is settled when the Attorney-General creates the League of Nations (Guarantee) Bill, which gives both Houses an opportunity to discuss and approve the application.

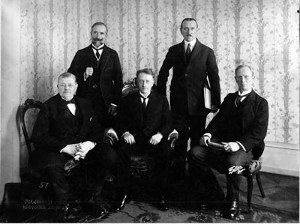

With this approval in September, Ireland is admitted as a full and equal member to the League of Nations on September 10, 1923, giving it access to the rest of the world. This membership means that Ireland now has representatives in one place, who can meet with other representatives, instead of sending delegates to each country. One location not only saves time, but money. Early Irish foreign policy is driven by the need to stress the country’s legal status as a platform from which to pursue a fuller foreign policy. With admission to the League of Nations this is now possible. Ireland’s acceptance into the League of Nations helps create legitimacy for the new nation.

(Pictured: Irish Delegation to the League of Nations, 1923)

About 200 Anti-Treaty

About 200 Anti-Treaty