William Smith O’Brien, Irish nationalist Member of Parliament (MP) and leader of the Young Ireland movement, is born in Dromoland, Newmarket-on-Fergus, County Clare, on October 17, 1803.

O’Brien is the second son of Sir Edward O’Brien, 4th Baronet, of Dromoland Castle. His mother is Charlotte Smith, whose father owns a property called Cahirmoyle in County Limerick. He takes the additional surname Smith, his mother’s maiden name, upon inheriting the property. He lives at Cahermoyle House, a mile from Ardagh, County Limerick. He is a descendant of the eleventh century Ard Rí (High King of Ireland), Brian Boru. He receives an upper-class English education at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge. Subsequently, he studies law at King’s Inns in Dublin and Lincoln’s Inn in London.

From April 1828 to 1831 O’Brien is Conservative MP for Ennis. He becomes MP for Limerick County in 1835, holding his seat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom until 1849.

Although a Protestant country-gentleman, O’Brien supports Catholic emancipation while remaining a supporter of British-Irish union. In 1843, in protest against the imprisonment of Daniel O’Connell, he joins O’Connell’s anti-union Repeal Association.

Three years later, O’Brien withdraws the Young Irelanders from the association. In January 1847, with Thomas Francis Meagher, he founds the Irish Confederation, although he continues to preach reconciliation until O’Connell’s death in May 1847. He is active in seeking relief from the hardships of the famine. In March 1848, he speaks out in favour of a National Guard and tries to incite a national rebellion. He is tried for sedition on May 15, 1848 but is not convicted.

On July 29, 1848, O’Brien and other Young Irelanders lead landlords and tenants in a rising in three counties, with an almost bloodless battle against police at Ballingarry, County Tipperary. In O’Brien’s subsequent trial, the jury finds him guilty of high treason. He is sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. Petitions for clemency are signed by 70,000 people in Ireland and 10,000 people in England. In Dublin on June 5, 1849, the sentences of O’Brien and other members of the Irish Confederation are commuted to transportation for life to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania in present-day Australia).

O’Brien attempts to escape from Maria Island off Tasmania, but is betrayed by the captain of the schooner hired for the escape. He is sent to Port Arthur where he meets up with John Mitchel.

O’Brien is a founding member of the Ossianic Society, which is founded in Dublin on St. Patrick’s Day 1853, whose aim is to further the interests of the Irish language and to publish and translate literature relating to the Fianna. He writes to his son Edward from Van Diemen’s Land, urging him to learn the Irish language. He himself studies the language and uses an Irish-language Bible, and presents to the Royal Irish Academy Irish-language manuscripts he has collected.

In 1854, after five years in Tasmania, O’Brien is released on the condition he never returns to Ireland. He settles in Brussels. In May 1856, he is granted an unconditional pardon and returns to Ireland that July. He contributes to The Nation newspaper, but plays no further part in politics.

In 1864 he visits England and Wales, with the view of rallying his failing health, but no improvement takes place and he dies in Bangor, Gwynedd, Wales on June 18, 1864.

A statue of William Smith O’Brien stands in O’Connell Street, Dublin. Sculpted in Portland limestone, it is designed by Thomas Farrell and erected in D’Olier Street, Dublin, in 1870. It is moved to its present position in 1929.

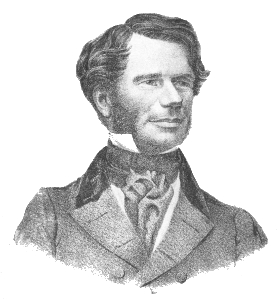

(Pictured: Portrait of William Smith O’Brien by George Francis Mulvany, National Gallery of Ireland)