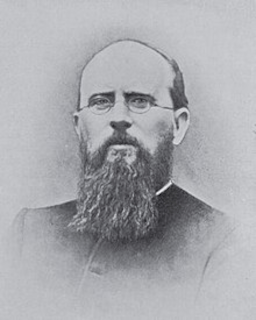

Christopher Augustine Reynolds, the first Catholic Archbishop of Adelaide, South Australia, is born in Dublin on August 11, 1834.

Reynolds is the son of Patrick Reynolds and his wife Elizabeth, née Bourke. Educated by the Carmelites at Clondalkin, Dublin, he later comes under the influence of the Benedictines when he volunteers for the Northern Territory mission of Bishop Rosendo Salvado Rotea, and is sent to Subiaco near Rome to train for the priesthood. He leaves after three years and goes to the Swan River Colony with Bishop Joseph Serra to continue his training at New Norcia, arriving at Fremantle in May 1855. Probably because of poor health, he leaves the Benedictines and in January 1857 goes to South Australia. He completes his training under the Jesuits at Sevenhill and is ordained in April 1860 by Bishop Patrick Geoghegan. He is parish priest at Wallaroo (where he builds the church at Kadina), Morphett Vale and Gawler. When Bishop Laurence Sheil dies in March 1872, he is appointed administrator of the diocese of Adelaide. On November 2, 1873, in Adelaide he is consecrated bishop by Archbishop John Bede Polding.

Reynolds has a large diocese and in 1872-80 travels over 52,000 miles in South Australia. The opening up of new agricultural districts, an increase in Irish migrants and diocesan debts had produced a grave shortage of clergy. But his most urgent problem is conflicts between and within the clergy and laity over education, especially the role to be played by the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Sacred Heart. He supports the Sisters, reopens schools closed by Archbishop Sheil and, though opposed by the Bishop of the Diocese of Bathurst Matthew Quinn, helps the Superior, Mother Mary MacKillop, secure Rome’s approval for autonomy for her Sisterhood.

Reynolds is not a good administrator and his strenuous efforts to extend Catholic education after the Education Act of 1875 incurs alarming debts. In 1880-81 he visits Rome. On his return, increasingly concerned with finances, disturbed at the prospect of losing St. Joseph nuns and, to some extent misled by jealousy and intrigue, he dramatically reverses his policy towards the Sisterhood and on November 14, 1883, relieves Mother Mary of her duties as Mother Superior. Though the Plenary Council of the Bishops of Australasia, held in Sydney in 1885, support him, in 1888 Pope Leo XIII decrees a central government for the Sisterhood, to be located in Sydney. The council requests that Adelaide be raised to an archiepiscopal and metropolitan see and on September 11, 1887, Reynolds is invested archbishop by Cardinal Francis Moran.

Reynolds’s health is never robust and after a two-year illness he dies on June 12, 1893, in Adelaide, where he is buried. Although he is austere and hard-working, he leaves his successor church debts of over £56,000. A particularly fine preacher, he is widely respected for his missionary zeal and for an ecumenical spirit unusual for his time.

(From: Australian Dictionary of Biography, http://www.adb.anu.edu.au, Ian J. Bickerton)