The Irish Catholic Hierarchy formally endorses Home Rule on February 16, 1886, a significant moment in the Irish political landscape.

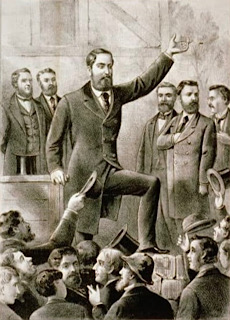

The Home Rule movement, led by Charles Stewart Parnell (pictured) and the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), seeks to establish a separate Irish parliament to handle domestic affairs while remaining within the British Empire. The campaign gains significant momentum throughout the late 19th century, but opposition from the British government and Irish unionists make progress difficult. Up to this point, the Catholic Church in Ireland had largely remained cautious about taking an overtly political stance on Home Rule. However, their endorsement on this day in 1886 changes the dynamic of the movement, giving it an unprecedented boost in legitimacy and support among the Irish people.

The Catholic Church plays a central role in Irish society, wielding immense influence over the daily lives of the majority Catholic population. Many of the clergy are already sympathetic to nationalist aspirations, but an official endorsement from the hierarchy signals a unified front that cannot be ignored. By formally backing Home Rule, the bishops strengthen nationalist demands and provide moral authority to the movement, reinforcing the argument that Home Rule is not just a political necessity but also a just and rightful cause.

This endorsement comes at a critical time. British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone is preparing to introduce the Government of Ireland Bill 1886, commonly known as the First Home Rule Bill, in April 1886, a legislative measure that, if passed, would grant Ireland limited self-government. The backing of the Catholic hierarchy is instrumental in rallying public support and reinforcing Parnell’s leadership. While the bill ultimately fails in the House of Commons on June 8, 1886, due to strong opposition from Conservative and Unionist factions, the Catholic Church’s stance ensures that Home Rule remains a dominant political issue for decades to come.

Despite the failure of the 1886 bill, the endorsement by the Catholic bishops has long-term implications. It solidifies a powerful alliance between Irish nationalism and the Church, an influence that persists well into the 20th century. The endorsement also helps to counteract Protestant unionist claims that Home Rule is merely a radical or sectarian endeavor, presenting it instead as a moderate and just political cause with widespread backing.

Over the following years, Home Rule remains a contentious issue, with subsequent attempts to pass similar legislation met with resistance. The Government of Ireland Bill 1893, commonly known as the Second Home Rule Bill, is again defeated in the House of Lords, and it is not until the Government of Ireland Act 1914, commonly referred to as the Third Home Rule Bill, that significant progress is made. Even then, implementation is delayed by World War I and ultimately overshadowed by the 1916 Easter Rising and the Irish War of Independence.

Looking back, the Catholic Church’s endorsement of Home Rule on February 16, 1886, is a defining moment in Ireland’s political history. It reinforces the nationalist cause, legitimizes the demand for self-governance, and plays a crucial role in shaping Ireland’s path toward eventual independence. While Home Rule itself is never fully realized in the form originally envisioned, its legacy influences the Irish Free State’s establishment in 1922 and Ireland’s eventual emergence as a fully independent republic.

(From: “February 16, 1886 – The Catholic Church Embraces Home Rule,” by Bagtown Clans, This Day in Irish History Substack, http://www.thisdayinirishhistory.substack.com, February 2025)