Thomas Aloysius Finlay, Irish judge, politician and barrister, is born on September 17, 1922, in Blackrock, Dublin. He serves as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Dublin South-Central constituency from 1954 to 1957, a Judge of the High Court from 1971 to 1985, President of the High Court from 1974 to 1985 and Chief Justice of Ireland and a Judge of the Supreme Court from 1985 to 1994.

Finlay is the second son of Thomas Finlay, a politician and senior counsel whose career is cut short by his early death in 1932. He is educated at Clongowes Wood College, University College Dublin (UCD) and King’s Inns. While attending UCD, he is elected Auditor of the University College Dublin Law Society. His older brother, William Finlay, serves as a governor of the Bank of Ireland.

Finlay is called to the Bar in 1944, practicing on the Midlands circuit and becomes a senior counsel in 1961.

Finlay is elected to Dáil Éireann as a Fine Gael TD for the Dublin South-Central constituency at the 1954 Irish general election. He loses his seat at the 1957 Irish general election.

Following his exit from politics in 1957, having lost his Dáil seat, Finlay resumes practicing as a barrister. He successfully defends Captain James Kelly in the infamous 1970 arms trial.

In 1971, Finlay is tasked by the Fianna Fáil government with representing Ireland before the European Commission of Human Rights, when, in response to the ill treatment of detainees by security forces in Northern Ireland, they charge the British government with torture. Despite the notional recourse such prisoners would have within the British legal system, the Commission rules the complaint admissible.

Finlay is subsequently appointed a High Court judge and President of the High Court in January 1974. In 1985, Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald and his government nominates him to the Supreme Court and to the office of Chief Justice of Ireland. On October 10, 1985, he is appointed by President Patrick Hillery to both roles.

During this period Finlay presides over a number of landmark cases, including Attorney General v X in 1992, when he overturns a High Court injunction preventing a pregnant teenage rape victim travelling to the UK for an abortion.

When, in the same year, Judge Liam Hamilton of the High Court, chair of the Beef Tribunal, seeks disclosure of the cabinet’s minutes for a particular meeting, Chief Justice Finlay along with the majority of the Supreme Court deny the request ruling that the concept of collective government responsibility in the Constitution takes precedence.

Finlay announces his resignation as Chief Justice of Ireland and retirement as a judge in 1994.

After his retirement, Finlay presides over a number of public inquiries.

In 1996, Finlay oversees the inquiry into the violence by English fans at the aborted 1995 friendly soccer match versus the Republic of Ireland at Lansdowne Road. His report to Bernard Allen, Minister for Sport, is critical of security arrangements on the night and recommends improvements to ticketing, seat-allocation, fan-vetting and policing arrangements. The Irish Government shares his report with the British Home Office.

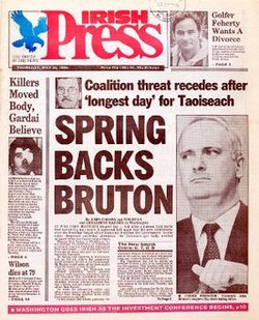

After the collapse of The Irish Press group in 1995, the Minister for Enterprise and Employment, John Bruton, receives a damming report from the Competition Authority that Independent Newspapers has abused its dominant position and acted in an anti-competitive manner by purchasing a shareholding in The Irish Press. In September 1995, Bruton announces the Commission on the Newspaper Industry with an extremely wide remit to examine diversity and ownership, competitiveness, editorial freedom and standards of coverage in Irish newspapers as well as the impact of the sales of the British press in Ireland. Minister Bruton appoints 21 people to the commission and appoints Finlay chair. Due to the wide remit and huge number of submissions, the commission’s report is delayed but is eventually published at the end of July recommending widespread reforms.

Following the discovery of the BTSB anti-D scandal, in 1996, Finlay is appointed the chair and singular member of the Tribunal of Inquiry into the Blood Transfusion Service Board. The speed and efficiency with which his BTSB Tribunal conducts its business, restores confidence in the Tribunal as a mechanism of resolving great controversies in the public interest.

Finlay also sits on an Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) panel to adjudicate on the cases of Rugby players accused of using banned performance-enhancing substances.

Finlay is married to Alice Blayney, who predeceases him in 2012. They have five children, two of whom follow in his family’s legal tradition: his son John being a Senior Counsel and his daughter Mary Finlay Geoghegan a former judge of the High Court, Court of Appeal and Supreme Court. Whenever his work schedule allows, he escapes to County Mayo where he indulges his passion for fishing.

Thomas Finlay dies at the age of 95 in Irishtown, Dublin, on December 3, 2017.