Oliver Cromwell abandons the First Siege of Waterford on December 2, 1649, and goes into winter quarters at Dungarvan. Waterford is besieged twice during 1649 and 1650 during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The town is held by Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, under General Richard Farrell and English Royalist troops under General Thomas Preston. It is besieged by English Parliamentarians under Cromwell, Michael Jones and Henry Ireton.

Waterford is a Catholic city and like most other towns in southeast Ireland, the populace has supported the Confederate Catholic cause since the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Late in 1641, Protestant refugees, displaced by the insurgents, begin to arrive in the town, creating tension among the Catholic townspeople. The city’s mayor wants to protect the refugees, but the recorder and several of the aldermen on the city council want to strip them of their property and let in the rebels, who arrive outside the walls in early 1642. At first, the Mayor’s faction is successful in refusing to admit rebel forces, but by March 1642, the faction in the municipal government sympathetic to the rebellion prevails. The Protestants in Waterford are expelled, in most cases put on ships to England, sometimes after having their property looted by the city mob. In 1645, Confederate troops under Thomas Preston besiege and capture nearby Duncannon from its English garrison, thus removing the threat to shipping coming to and from Waterford.

Waterford’s political community is noted for its intransigent Catholic politics. In 1646, a synod of Catholic Bishops, based in Waterford, excommunicate any Catholic who supports a treaty between the Confederates and English Royalists, which does not allow for the free practice of the Catholic religion. The Confederates finally agree to a treaty with Charles I of England in 1648, in order to join forces with the Royalists against their common enemy, the English Parliament, which is both anti-Catholic and hostile to the King. The Parliamentarians land a major expeditionary force in Ireland at Dublin, under Cromwell in August 1649.

The English Parliamentarian New Model Army arrives to besiege Waterford in October 1649. One of the stated aims of Cromwell’s invasion of Ireland is to punish the Irish for the mistreatment of Protestants in 1641. Given Waterford’s history of partisan Catholic politics, this provokes great fear amongst the townspeople. This fear is accentuated by the fate of Drogheda and nearby Wexford which had recently been taken and sacked by Cromwell’s forces and their garrisons massacred.

Waterford is very important strategically in the war in Ireland. Its port allows for the importation of arms and supplies from continental Europe and its geographical position commands the entrance of the rivers Suir and Barrow.

Before besieging Waterford, Cromwell has to take the surrounding garrisons held by Royalist and Confederate troops in order to secure his lines of communication and supply. Duncannon, whose fort commands the sea passage into Waterford, is besieged by Parliamentarians under Ireton from October 15 to November 5. However, due to a stubborn defence, the garrison there under Edward Wogan holds out. This means that heavy siege artillery cannot be brought up to Waterford by sea.

New Ross surrenders to Cromwell on October 19 and Carrick-on-Suir is taken on November 19. A counterattack on Carrick by Irish troops from Ulster under a Major Geoghegan is repulsed on November 24, leaving 500 of the Ulstermen dead.

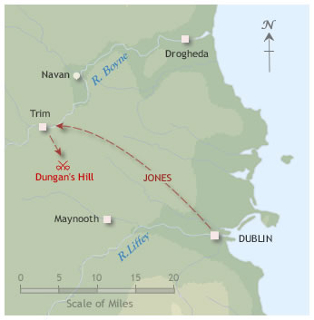

Having isolated Waterford from the east and north, Cromwell arrives before the city on November 24. However, Waterford still has access to reinforcements from the west and up to 3,000 Irish soldiers from the Confederate’s Ulster Army under Richard O’Farrell are fed into the city in the course of a week. O’Farrell, having been a successful officer in the Spanish Army, is highly trained and experienced in siege warfare from battles in Flanders. Cromwell has come up against a superior minded soldier and commander. The weather is extremely cold and wet, and the Parliamentarian troops suffer heavily from disease. Out of 6,500 English Parliamentarian soldiers who besiege Waterford in 1649, only 3,000 or so are still fit by the time the siege is called off. Added to this, Cromwell is able to make little headway in taking the city. The capture of a fort at Passage East enables him to bring up siege guns by sea, but the wet weather means that it is all but impossible to transport them close enough to Waterford’s walls to use them. Farrell proves tactically superior in defending Waterford and repels Cromwell’s attempts. Eventually Cromwell has to call off the siege on December 2 and go into winter quarters at Dungarvan. Among his casualties is his commander Michael Jones, who dies of disease.