The Drumcree conflict or Drumcree standoff is a dispute over yearly Orange Order parades in the town of Portadown, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The town is mainly Protestant and hosts numerous Protestant/loyalists marches each summer but has a significant Catholic minority. The Orange Order, a Protestant unionist organization, insists that it should be allowed to march its traditional route to and from Drumcree Church on the Sunday before The Twelfth. However, most of the route is through the mainly Catholic/Irish nationalist section of town. The residents, who see the march as sectarian, triumphalist and supremacist, seek to ban it from their area. The Orangemen see this as an attack on their traditions as they have marched the route since 1807, when the area was mostly farmland.

In 1995 and 1996, residents succeed in stopping the march. This leads to a standoff at Drumcree between the security forces and thousands of Orangemen/loyalists. Following a wave of loyalist violence, police allow the march through. In 1997, security forces lock down the Catholic area and let the march through, citing loyalist threats to kill Catholics if they are stopped. This sparks widespread protests and violence by Irish nationalists. From 1998 onward, the march is banned from Garvaghy Road and the army seals off the Catholic area with large steel, concrete and barbed wire barricades. Each year there is a major standoff at Drumcree and widespread loyalist violence. Since 2001 things have been relatively calm but moves to get the two sides into face-to-face talks have failed.

Early in 1998 the Public Processions (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 is passed, establishing the Parades Commission. The Commission is responsible for deciding what route contentious marches should take. On June 29, 1998, the Parades Commission decides to ban the march from Garvaghy Road.

On Friday, July 3, about 1,000 soldiers and 1,000 police are deployed in Portadown. The soldiers build large barricades made of steel, concrete and barbed wire across all roads leading into the nationalist area. In the fields between Drumcree Church and the nationalist area they dig a trench, fourteen feet wide, which is then lined with rows of barbed wire. Soldiers also occupy the Catholic Drumcree College, St. John the Baptist Primary School and some properties near the barricades.

On Sunday, July 5, the Orangemen march to Drumcree Church and state that they will remain there until they are allowed to proceed. About 10,000 Orangemen and loyalists arrive at Drumcree from across Northern Ireland. A loyalist group calling itself “Portadown Action Command” issues a statement which reads, “As from midnight on Friday 10 July 1998, any driver of any vehicle supplying any goods of any kind to the Gavaghy Road will be summarily executed.”

Over the next ten days, there are loyalist protests and violence across Northern Ireland in response to the ban. Loyalists block roads and attack the security forces as well as Catholic homes, businesses, schools and churches. On July 7, the mainly Catholic village of Dunloy is “besieged” by over 1,000 Orangemen. The County Antrim Grand Lodge says that its members have “taken up positions” and “held” the village. On July 8, eight blast bombs are thrown at Catholic homes in the Collingwood area of Lurgan. There are also sustained attacks on the security forces at Drumcree and attempts to break through the blockade. On July 9, the security forces at Drumcree are attacked with gunfire and blast bombs. They respond with plastic bullets. The police recorded 2,561 “public order incidents” throughout Northern Ireland.

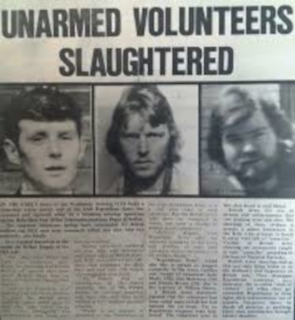

On Sunday, July 12, brothers Jason (aged 8), Mark (aged 9) and Richard Quinn (aged 10) are burned to death when their home is petrol bombed by loyalists. The boys’ mother is a Catholic and their home is in a mainly-Protestant section of Ballymoney. Following the murders, William Bingham, County Grand Chaplain of Armagh and member of the Orange Order negotiating team, says that “walking down the Garvaghy Road would be a hollow victory, because it would be in the shadow of three coffins of little boys who wouldn’t even know what the Orange Order is about.” He says that the Order has lost control of the situation and that “no road is worth a life.” However, he later apologizes for implying that the Order is responsible for the deaths. The murders provoke widespread anger and calls for the Order to end its protest at Drumcree. Although the number of protesters at Drumcree drops considerably, the Portadown lodges vote unanimously to continue their standoff.

On Wednesday, July 15, the police begin a search operation in the fields at Drumcree. A number of loyalist weapons are found, including a homemade machine gun, spent and live ammunition, explosive devices, and two crossbows with more than a dozen homemade explosive arrows.