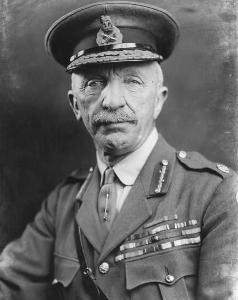

The Auxiliary Division, generally known as the Auxiliaries or Auxies, a paramilitary unit of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) during the Irish War of Independence (1919-21), is founded on July 27, 1920, by Major-General Henry Hugh Tudor. It is made up of former British Army officers, most of whom come from Great Britain and had fought in World War I.

In September 1919, the Commander-in-Chief, Ireland, Sir Frederick Shaw, suggests that the police force in Ireland be expanded via the recruitment of a special force of volunteer British ex-servicemen. During a Cabinet meeting on May 11, 1920, the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, suggests the formation of a “Special Emergency Gendarmerie, which would become a branch of the Royal Irish Constabulary.” Churchill’s proposal is referred to a committee chaired by General Sir Nevil Macready, Commander-in-Chief of the British forces in Ireland. Macready’s committee rejects Churchill’s proposal, but it is revived two months later, in July, by the Police Adviser to the Dublin Castle administration in Ireland, Major-General Henry Hugh Tudor. In a memo dated July 6, 1920, Tudor justifies the scheme on the grounds that it will take too long to reinforce the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) with ordinary recruits. Tudor’s new “Auxiliary Force” is to be strictly temporary with its members enlisting for a year. Their pay is to be £7 per week (twice what a constable is paid), plus a sergeant’s allowances, and are to be known as “Temporary Cadets.” At that time, one of high unemployment, a London advertisement for ex-officers to manage coffee stalls at two pounds ten shillings a week receives five thousand applicants.

The Auxiliary Division is recruited in Great Britain from among ex-officers who had served in World War I, especially those who had served in the British Army (including the Royal Flying Corps). Most recruits are from Britain, although some are from Ireland, and others come from other parts of the British Empire. Many have been highly decorated in the war and three, James Leach, James Johnson, and George Onions, have been awarded the Victoria Cross (VC). Enlisted men who had been commissioned as officers during the war often find it difficult to adjust to their loss of status and pay in civilian life, and some historians have concluded that the Auxiliary Division recruited large numbers of these “temporary gentlemen.”

Piaras Béaslaí, a former senior member of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) who supports the Anglo-Irish Treaty, while paying tribute to the bravery of the Auxiliaries, notes that the force is not composed exclusively of ex-officers but contains “criminal elements,” some of whom robbed people on the streets of Dublin and in their homes.

Recruiting began in July 1920, and by November 1921, the division is 1,900 strong. The Auxiliaries are nominally part of the RIC, but actually operate more or less independently in rural areas. Divided into companies, each about one hundred strong, heavily armed and highly mobile, they operate in ten counties, mostly in the south and west, where IRA activity is greatest. They wear either RIC uniforms or their old army uniforms with appropriate police badges, along with distinctive tam o’ shanter caps. They are commanded by Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier.

The elite ex-officer division proves to be much more effective than the Black and Tans especially in the key area of gathering intelligence. Auxiliary companies are intended as mobile striking and raiding forces, and they score some notable successes against the IRA. On November 20, the night before Bloody Sunday, they capture Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, the commandant and vice-commandant of the IRA’s Dublin Brigade, and murder them in Dublin Castle. That same night, they catch Liam Pilkington, commandant of the Sligo IRA, in a separate raid. A month later, in December, they catch Ernie O’Malley completely by surprise in County Kilkenny. He is reading in his room when a Temporary Cadet opens the door and walks in. “He was as unexpected as death,” says O’Malley. In his memoirs, the commandant of the Clare IRA, Michael Brennan, describes how the Auxiliaries nearly capture him three nights in a row.

IRA commanders become concerned about the morale of their units as to many Volunteers the Auxiliaries seem to be “super fighters and all but invincible.” Those victories which are won over the Auxiliaries are among the most celebrated in the Irish War of Independence. On November 28, 1920, for example, a platoon of Auxiliaries is ambushed and wiped out in the Kilmichael Ambush by Tom Barry and the 3rd Cork Brigade. A little more than two months later, on February 2, 1921, another platoon of Auxiliaries is ambushed by Seán Mac Eoin and the North Longford Flying Column in the Clonfin Ambush. On March 19, 1921, the 3rd Cork Brigade of the IRA defeats a large-scale attempt by the British Army and Auxiliary Division to encircle and trap them at Crossbarry. On April 15, 1921, Captain Roy Mackinnon, commanding officer of H Company of the Auxiliary Division, is assassinated by the Kerry IRA.

Successes require reliable intelligence and raids often bring no result — or sometimes worse. In one case, they arrest a Castle official, Law Adviser W. E. Wylie, by mistake. In another, more notorious case, on April 19, 1921, they raid the Shannon Hotel in Castleconnell, County Limerick, on a tip that there are suspicious characters drinking therein. The “suspicious characters” turn out to be three off-duty members of the RIC. Both sides mistake the other for insurgents and open fire. Three people, an RIC man, an Auxiliary Cadet and a civilian, are killed in the shootout that follows.

The Auxiliary Division is disbanded along with the RIC in 1922. Although the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty requires the Irish Free State to assume responsibility for the pensions of RIC members, the Auxiliaries are explicitly excluded from this provision. Following their disbandment, many of its former personnel join the Palestine Police Force in the British-controlled territory.

The anti-insurgency activities of the Auxiliaries Division have become interchangeable with those conducted by the Black and Tans, leading to many atrocities committed by them being attributed to the Black and Tans. Nevertheless, both British units remain equally reviled in Ireland.

The Auxiliaries are featured in historical drama films like Michael Collins, The Last September, and The Wind That Shakes the Barley.

(Pictured: Cap badge design for F Company of the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary)