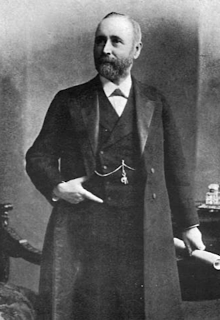

William James Pirrie, 1st Viscount Pirrie, KP, PC, PC (Ire), a leading British shipbuilder and businessman, is born on May 31, 1847, in Quebec City, Canada East, Province of Canada. He is chairman of Harland & Wolff, shipbuilders, between 1895 and 1924, and also serves as Lord Mayor of Belfast between 1896 and 1898.

Pirrie is taken back to Ireland when he is two years old and spends his childhood at Conlig House, also known as Little Clandeboye Conlig, County Down. Belonging to a prominent family, his nephews included J. M. Andrews, who later becomes Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Thomas Andrews, builder of RMS Titanic, and Sir James Andrews, 1st Baronet, the Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland.

Pirrie is educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution before entering Harland & Wolff shipyard as a gentleman apprentice in 1862. Twelve years later he is made a partner in the firm, and on the death of Sir Edward Harland in 1895, he becomes its chairman, a position he holds until his death. As well as overseeing the world’s largest shipyard, he is elected Lord Mayor of Belfast in 1896, and is re-elected to the office as well as made an Irish Privy Counsellor the following year. He becomes Belfast’s first honorary freeman in 1898, and serves in the same year as High Sheriff of Antrim and subsequently of County Down. In February 1900, he is elected President of the UK Chamber of Shipping, where he had been vice-president the previous year. He helps finance the Liberals in Ulster in the 1906 United Kingdom general election, and that same year, at the height of Harland & Wolff’s success, he is raised to the peerage as Baron Pirrie, of the City of Belfast.

In 1907, Pirrie is appointed Comptroller of the Household to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and in 1908 is appointed Knight of St Patrick (KP). Pro-Chancellor of Queen’s University of Belfast (QUB) from 1908 to 1914, he is also in the years before World War I a member of the Committee on Irish Finance as well as Lord Lieutenant of Belfast.

In February 1912, after chairing a famous meeting of the Ulster Liberal Association at which Winston Churchill defends the government’s policy of Home Rule for Ireland, Pirrie is jeered on the streets of Belfast, and assaulted as he boards a steamer in Larne: pelted with rotten eggs, herrings, and bags of flour. In 1910, the Ulster Liberal Association, an overwhelmingly Protestant body, with a weekly newspaper, and branch network throughout Ulster, adopts (in opposition to the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association) an explicitly pro-home rule position.

In the months leading up to the 1912 sinking of the RMS Titanic, Pirrie is questioned about the number of life boats aboard the Olympic-class ocean liners. He responds that the great ships are unsinkable and the rafts are to save others. This haunts him for the rest of his life. In April 1912, Pirrie is to travel aboard RMS Titanic, but illness prevents him.

During the war Pirrie is a member of the War Office Supply Board, and in 1918 becomes Comptroller-General of Merchant Shipbuilding, organising British production of merchant ships.

In 1921, Pirrie is elected to the Senate of Northern Ireland, and that same year is created Viscount Pirrie of the City of Belfast, in the honours for the opening of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in July 1921, for his war work and charity work. In Belfast he is, on other grounds, already a controversial figure: a Protestant employer associated as a leading Liberal with a policy of Home Rule for Ireland.

In March 1924, Pirrie, his wife, and her sister sail on a Royal Mail Steam Packet Company liner from Southampton on a business trip to South America. They travel overland from Buenos Aires to Chile, where they embark aboard the Pacific Steam Navigation Company‘s Ebro. Pirrie comes down with pneumonia in Antofagasta, and his condition worsens when the ship reaches Iquique. At Panama City two nurses embark to care for him. By then he is very weak, but insists on being brought on deck to see the canal. He admires how Ebro is handled through the locks.

Pirrie dies at sea off Cuba on June 7, 1924. His body is embalmed. On June 13, Ebro reaches Pier 42 on the North River in New York City, where Pirrie’s friend Andrew Weir, 1st Baron Inverforth and his wife meet Viscountess Pirrie and her sister. UK ships in the port of New York lower their flags to half-mast, and Pirrie’s body is transferred to Pier 59, where it is embarked on White Star Line‘s RMS Olympic, one of the largest ships Pirrie ever built, to be repatriated to the UK. He is buried in Belfast City Cemetery. The barony and viscountcy die with him. Lady Pirrie dies on June 19, 1935. A memorial to Pirrie in the grounds of Belfast City Hall is unveiled in 2006.