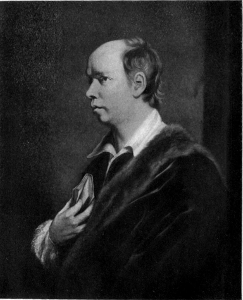

Oliver Goldsmith, Irish novelist, playwright, and poet best known for his novel The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), his pastoral poem The Deserted Village (1770), and his plays The Good-Natur’d Man (1768) and She Stoops to Conquer (1771, first performed in 1773), dies in London on April 4, 1774. He is thought to have written the classic children’s tale The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes (1765).

Goldsmith’s birth date and location are not known with certainty, although he reportedly tells a biographer that he was born on November 10, 1728. The location of his birthplace is either in the townland of Pallas, near Ballymahon, County Longford, where his father is the Anglican curate of the parish of Forgney, or at the residence of his maternal grandparents, at the Smith Hill House near Elphin, County Roscommon, where his grandfather Oliver Jones is a clergyman and master of the Elphin diocesan school, which is where Goldsmith studies. When Goldsmith is two years old, his father is appointed the rector of the parish of “Kilkenny West” in County Westmeath. The family moves to the parsonage at Lissoy, between Athlone and Ballymahon, and continues to live there until his father’s death in 1747.

In 1744 Goldsmith enters Trinity College, Dublin. His tutor is Theaker Wilder. Neglecting his studies in theology and law, he falls to the bottom of his class. In 1747, along with four other undergraduates, he is expelled for a riot in which they attempt to storm the Marshalsea Prison. He is graduated in 1749 as a Bachelor of Arts, but without the discipline or distinction that might have gained him entry to a profession in the church or the law. His education seems to have given him mainly a taste for fine clothes, playing cards, singing Irish airs, and playing the flute. He lives for a short time with his mother, tries various professions without success, studies medicine desultorily at the University of Edinburgh from 1752 to 1755, and sets out on a walking tour of Flanders, France, Switzerland, and Northern Italy.

Goldsmith settles in London in 1756, where he briefly holds various jobs, including an apothecary‘s assistant and an usher of a school. Perennially in debt and addicted to gambling, Goldsmith produces a massive output as a hack writer for the publishers of London, but his few painstaking works earn him the company of Samuel Johnson, with whom he is a founding member of “The Club.” There, through fellow Club member Edmund Burke, he makes the acquaintance of Sir George Savile, who later arranges a job for him at Thornhill Grammar School. The combination of his literary work and his dissolute lifestyle leads Horace Walpole to give him the epithet “inspired idiot.” During this period, he uses the pseudonym “James Willington,” the name of a fellow student at Trinity, to publish his 1758 translation of the autobiography of the Huguenot Jean Marteilhe.

Goldsmith is described by contemporaries as prone to envy, a congenial but impetuous and disorganised personality who once planned to emigrate to America but failed because he missed his ship. At some point around this time he works at Thornhill Grammar School, later basing Squire Thornhill on his benefactor Sir George Savile and certainly spending time with eminent scientist Rev. John Mitchell, whom he probably knows from London. Mitchell sorely misses good company, which Goldsmith naturally provides in spades. Thomas De Quincey writes of him “All the motion of Goldsmith’s nature moved in the direction of the true, the natural, the sweet, the gentle.”

His premature death in 1774 is believed to have been partly due to his own misdiagnosis of a kidney infection. Goldsmith is buried in Temple Church in London. There is a monument to him in the centre of Ballymahon and also in Westminster Abbey with an epitaph written by Samuel Johnson.