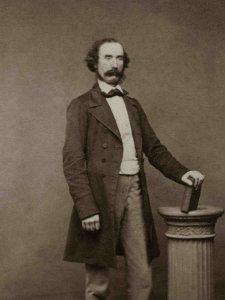

Robert Mallet, geophysicist, civil engineer, and inventor who distinguishes himself in research on earthquakes and is sometimes called the Father of Seismology, is born in Dublin on June 3, 1810.

Mallet is the son of factory owner John Mallet. He is educated at Trinity College, Dublin, entering it at the age of 16 and graduating in science and mathematics in 1830 at the age of 20.

Following his graduation, Mallet joins his father’s iron foundry business and helps build the firm into one of the most important engineering works in Ireland, supplying ironwork for railway companies, the Fastnet Rock lighthouse, and a swing bridge over the River Shannon at Athlone. He also helps manufacture the characteristic iron railings that surround Trinity College, and which bear his family name at the base.

Mallet is elected to the Royal Irish Academy in 1832 at the early age of 22. He also enrolls in the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1835 which helps finance much of his research in seismology.

In 1838 Mallet becomes a life member of the Royal Geological Society of Ireland and serves as its President from 1846–1848. From 1848–1849 he constructs the Fastnet Rock lighthouse, southwest of Cape Clear.

On February 9, 1846, Mallet presents to the Royal Irish Academy his paper On the Dynamics of Earthquakes, which is considered to be one of the foundations of modern seismology. He is also credited with coining the word “seismology” and other related words which he uses in his research. He also coins the term epicentre.

From 1852 to 1858, Mallet is engaged in the preparation of his work, The Earthquake Catalogue of the British Association (1858) and carries out blasting experiments to determine the speed of seismic propagation in sand and solid rock.

On December 16, 1857, the area around Padula, Italy is devastated by the Great Neapolitan earthquake which causes 11,000 deaths. At the time it is the third largest known earthquake in the world and has been estimated to have been of magnitude 6.9 on the Richter Scale. Mallet, with letters of support from Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin, petitions the Royal Society of London and receives a grant of £150 to go to Padula and record at first hand the devastation. The resulting report is presented to the Royal Society as the Report on the Great Neapolitan Earthquake of 1857. It is a major scientific work and makes great use of the then new research tool of photography to record the devastation caused by the earthquake. In 1862, he publishes the Great Neapolitan Earthquake of 1857: The First Principles of Observational Seismology in two volumes. He brings forward evidence to show that the depth below the Earth’s surface, from where the impulse of the Neapolitan earthquake originated, is about 8–9 geographical miles.

One of Mallet’s papers is Volcanic Energy: An Attempt to develop its True Origin and Cosmical Relations, in which he seeks to show that volcanic heat may be attributed to the effects of crushing, contortion, and other disturbances in the crust of the earth. The disturbances leading to the formation of lines of fracture, more or less vertical, down which water would find its way, and if the temperature generated be sufficient volcanic eruptions of steam or lava would follow.

Mallet is elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1854, and in 1861 moves to London, where he becomes a consulting engineer and edits The Practical Mechanic’s Journal. He is awarded the Telford Medal by the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1859, followed by the Cunningham Medal of the Royal Irish Academy for his research into the theory of earthquakes in 1862, and the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society of London in 1877, the Geological Society’s highest award.

Blind for the last seven years of his life, Robert Mallet dies at Stockwell, London, on November 5, 1881, and is buried at West Norwood Cemetery.