The Battle of Ballinamuck takes place at Ballinamuck, County Longford, on September 8, 1798, marking the defeat of the main force of the French incursion during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

The victory of General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert at the Battle of Castlebar, despite gaining him around 5,000 extra Irish recruits, did not lead to a renewed outbreak of the rebellion in other areas as hoped. The defeat of the earlier revolt devastated the Irish republican movement to the extent that few are willing to renew the struggle. A massive British force of 26,000 men is assembled under Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, the new Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and is steadily moving west. Humbert abandons Castlebar and moves toward Ulster, with the apparent intention of igniting an uprising there. He defeats a blocking force of government troops at Collooney in County Sligo. Following reports that rebellions have broken out in County Westmeath and County Longford, he alters course.

Humbert crosses the River Shannon at Ballintra Bridge on September 7, destroying it behind them, and continues to Drumshanbo where they spend the night – halfway between his landing-point and Dublin. News reaches him of the defeat of the Westmeath and Longford rebels at Wilson’s Hospital School at Multyfarmham and Granard from the trickle of rebels who have survived the slaughter and reached his camp. With Cornwallis’ huge force blocking the road to Dublin, facing constant harassment of his rearguard and the pending arrival of General Gerard Lake‘s command, Humbert decides to make a stand the next day at the townland of Ballinamuck on the Longford/Leitrim county border.

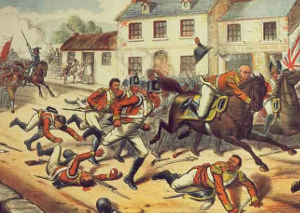

Humbert faces over 12,000 Irishmen and English forces. General Lake is close behind with 14,000 men, and Cornwallis is on his right at Carrick-on-Shannon with 15,000. The battle begins with a short artillery duel followed by a dragoon charge on exposed Irish rebels. There is a brief struggle when French lines are breached which only ceases when Humbert signals his intention to surrender and his officers order their men to lay down their muskets. The battle lasts little more than an hour.

While the French surrender is being taken, the 1,000 or so Irish allies of the French under Colonel Bartholomew Teeling, an Irish officer in the French army, hold onto their arms without signaling the intention to surrender or being offered terms. An attack by infantry followed by a dragoon charge breaks and scatters the Irish who are pursued into a bog where they are either bayoneted or drowned.

A total of 96 French officers and 746 men are taken prisoner. British losses are initially reported as 3 killed and 16 wounded or missing, but the number of killed alone is later reported as twelve. Approximately 500 French and Irish lay dead on the field. Two hundred Irish prisoners are taken in the mopping-up operations, almost all of whom are later hanged, including Matthew Tone, brother of Wolfe Tone. The prisoners are moved to the Carrick-on-Shannon Gaol. The French are given prisoner or war status however the Irish are not and some are hanged and buried in St. Johnstown, today known as Ballinalee, where most are executed in a field that is known locally as Bully’s Acre.

Humbert and his men are transported by canal to Dublin and exchanged for British prisoners of war. Government forces subsequently slowly spread out into the rebel-held “Irish Republic,” engaging in numerous skirmishes with rebel holdouts. These sweeps reach their climax on September 23 when Killala is captured by government forces. During these sweeps, suspected rebels are frequently summarily executed while many houses thought to be housing rebels are burned. French prisoners of war are swiftly repatriated, while United Irishmen rebels are executed. Numerous rebels take to the countryside and continue guerrilla operations, which take government forces some months to suppress. The defeat at Ballinamuck leaves a strong imprint on Irish social memory and features strongly in local folklore. Numerous oral traditions are later collected about the battle, principally in the 1930’s by historian Richard Hayes and the Irish Folklore Commission.

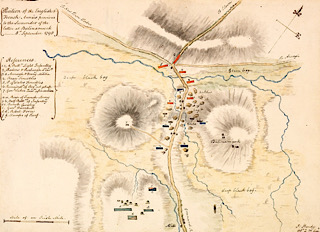

(Pictured: Watercolour plan by an I. Hardy of the Battle of Ballinamuck in County Longford on September 8, 1798, showing position of the English & French Armies previous to the surrender of the latter at Balinamuck)