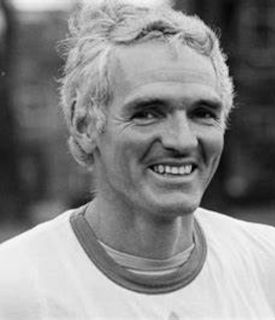

William Augustine Whelan, known as Billy Whelan or Liam Whelan, Irish footballer who plays as an inside-forward, is born at 28 St. Attracta’s Road, Cabra, Dublin, on April 1, 1935. He dies at the age of 22, as one of eight Manchester United players who are killed in the Munich air disaster.

Whelan is the fourth of seven children born to John and Elizabeth Whelan. His father is an accomplished centre half-back for Dublin club Brunswick and is instrumental in winning the FAI Junior Shield in 1924. His mother is an avid Shamrock Rovers supporter. His father dies in 1943 when Whelan is just eight years old.

Whelan plays Gaelic games, winning a medal for St. Peter’s national school in nearby Phibsborough. After leaving school at the age of fourteen, he works in Cassidy’s, an outfitter on South Great George’s Street. He is an accomplished Gaelic footballer and hurler, but association football is his first love.

Whelan begins his career at the age of twelve when he joins Home Farm before joining Manchester United as an 18-year-old in 1953. He is capped four times for the Republic of Ireland national football team, including a surprising 4–1 victory against Holland in Rotterdam in 1956, but does not score. His brother John plays for Shamrock Rovers and Drumcondra and his eldest brother Christy plays for Transport.

Whelan makes his first appearance for Manchester United during the 1954–55 season and quickly becomes a regular first-team player. He goes on to make 98 first-team appearances in four seasons at United, scoring 52 goals. He is United’s top scorer in the 1956–57 season, scoring 26 goals in the First Division and 33 in all competitions as United wins their second successive league title and reaches the semi-finals of the 1957-58 European Cup. He also gives a commanding display in the 1957 FA Cup final despite losing 2–1 to Aston Villa. Such is the strength of the competition in the United first team that he is soon being kept out of the side by Bobby Charlton. He is a traveling reserve for United’s ill-fated European Cup match against Red Star Belgrade in Belgrade on February 6, 1958, and is one of eight players to die in the subsequent air crash that destroys Matt Busby‘s young team and claims twenty-three lives. Fellow Irishman Harry Gregg, United’s goalkeeper and a survivor and hero of the Munich air crash, recalls Whelan’s last words as the plane is attempting take-off for the third and final time as “Well, if this is the time, then I’m ready.”

Thousands attend Whelan’s funeral on February 12 in St. Peter’s Church, Phibsborough, Dublin, and line the streets as the funeral procession makes its way to his burial-place in Glasnevin Cemetery. In December 2006 Dublin Corporation unveils a commemorative plaque on a bridge at Faussagh Road, Cabra, which was renamed Liam Whelan Bridge.

Although of a cheerful disposition, Whelan is also modest and shy by nature, and a quietly devout Catholic. He has a particular dislike of swearing and tends to fix a look of pained disappointment on teammates who use bad language. Nobby Stiles admits that he “would rather be caught swearing by the pope than by Billy Whelan.” His religious devotion regularly fuels rumours that he is considering being a priest, although at the time of his death he is engaged to be married to Ruby McCullough.