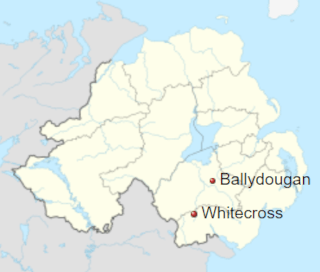

The Reavey and O’Dowd killings are two coordinated gun attacks on January 4, 1976, in County Armagh, Northern Ireland. Six Catholic civilians die after members of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group, break into their homes and shoot them. Three members of the Reavey family are shot at their home in Whitecross and four members of the O’Dowd family are shot at their home in Ballydougan. Two of the Reaveys and three of the O’Dowds are killed outright, with the third Reavey victim dying of brain hemorrhage almost a month later.

In February 1975, the Provisional Irish Republican Army and the British Government enter into a truce and restart negotiations. For the duration of the truce, the IRA agrees to halt its attacks on the British security forces, and the security forces mostly end their raids and searches. However, there are dissenters on both sides. There is a rise in sectarian killings during the truce, which “officially” lasts until February 1976.

The shootings are part of a string of attacks on Catholics and Irish nationalists by the “Glenanne gang,” an alliance of loyalist militants, rogue British soldiers and Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) police officers. Billy McCaughey, an officer from the Special Patrol Group (SPG), admits taking part and accuses another officer of involvement. His colleague John Weir says those involved include a British soldier, two police officers and an alleged police agent, Robin “the Jackal” Jackson.

At about 6:10 p.m., at least three masked men enter the home of the Reaveys, a Catholic family, in Whitecross, through a door that had been left unlocked. Brothers John (24), Brian (22) and Anthony Reavey (17) are alone in the house and are watching television in the sitting room. The gunmen open fire on them with two 9mm Sterling submachine guns, a 9mm Luger pistol and a .455 Webley revolver. John and Brian are killed outright. Anthony manages to run to the bedroom and take cover under a bed. He is shot several times and is left for dead. After searching the house and finding no one else, the gunmen leave. Badly wounded, Anthony crawls about 200 yards to a neighbour’s house to seek help. He dies of a brain haemorrhage on January 30. Although the pathologist says the shooting played no part in his death, Anthony is listed officially as a victim of the Troubles. A brother, Eugene Reavey, says “Our entire family could have been wiped out. Normally on a Sunday, the twelve of us would have been home, but that night my mother took everybody [else] out to visit my aunt.” Neighbours claim there had been two Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) checkpoints set up — one at either end of the road — around the time of the attack. These checkpoints are to stop passers-by from seeing what is happening. The RUC denies having patrols in the area at the time but says there could have been checkpoints manned by the British Army‘s Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

At about 6:20 p.m., three masked men burst into the home of the O’Dowds, another Catholic family, in Ballydougan, about fifteen miles away. Sixteen people are in the house for a family reunion. The male family members are in the sitting room with some of the children, playing the piano. The gunmen spray the room with bullets, killing Joseph O’Dowd (61) and his nephews Barry (24) and Declan O’Dowd (19). All three are members of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and the family believes this is the reason they are targeted. Barney O’Dowd, Barry and Declan’s father, is also wounded by gunfire. The RUC concludes that the weapon used is a 9mm Sterling submachine gun, although Barney believes a Luger pistol with a suppressor was also used. The gunmen had crossed a field to get to the house, and there is evidence that UDR soldiers had been in the field the day before.

The following day, gunmen stop a minibus carrying ten Protestant workmen near Whitecross and shoot them dead by the roadside. This becomes known as the Kingsmill massacre. The South Armagh Republican Action Force (SARAF) claims responsibility, saying it is retaliation for the Reavey and O’Dowd killings. Following the massacre, the British Government declares County Armagh to be a “Special Emergency Area” and announces that the Special Air Service (SAS) is being sent into South Armagh.

Some of the Reavey family come upon the scene of the Kingsmill massacre while driving to the hospital to collect the bodies of John and Brian. Some members of the security forces immediately begin a campaign of harassment against the Reavey family and accuse Eugene Reavey of orchestrating the Kingsmill massacre. On their way home from the morgue, the Reavey family are stopped at a checkpoint. Eugene claims the soldiers assaulted and humiliated his mother, put a gun to his back, and danced on his dead brothers’ clothes. The harassment would later involve the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment. In 2007, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) apologises for the “appalling harassment suffered by the family in the aftermath at the hands of the security forces.”

After the killings of the Reavey brothers, their father makes his five surviving sons swear not to retaliate or to join any republican paramilitary group.

In 1999, Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) leader Ian Paisley states in the House of Commons that Eugene Reavey “set up the Kingsmill massacre.” In 2010, a report by the police Historical Enquiries Team clears Eugene of any involvement. The Reavey family seeks an apology, but Paisley refuses to retract the allegation and dies in 2014.