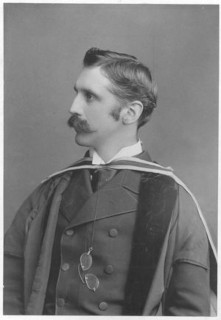

Samuel Henry Butcher, Anglo-Irish classical scholar and politician, dies in London on December 29, 1910.

Butcher is born in Dublin on April 16, 1850, the son of Samuel Butcher, Bishop of Meath, and Mary Leahy. John Butcher, 1st Baron Danesfort, is his younger brother. He is educated at Marlborough College in Wiltshire and then receives a place at Trinity College, Cambridge, attending between 1869 and 1873 where he is Senior Classic and Chancellor’s medalist. He is elected fellow of Trinity in 1874.

Butcher leaves Trinity on his marriage, in 1876, to Rose Julia Trench (1840-1902), the daughter of Archbishop Richard Chenevix Trench. The marriage produces no children.

From 1876 to 1882 Butcher is a fellow of University College, Oxford, and tutors there. From 1882 to 1903 he is Professor of Greek at the University of Edinburgh succeeding Prof. John Stuart Blackie. During this period, he lives at 27 Palmerston Place in Edinburgh‘s West End. He is succeeded at the University of Edinburgh by Prof. Alexander William Mair.

Butcher is one of the two Members of Parliament for Cambridge University, between 1906 and his death, representing the Liberal Unionist Party. He is President of the British Academy from 1909 to 1910.

Butcher dies in London on December 29, 1910, and his body is returned to Scotland and interred at the Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh with his wife. His grave has a pale granite Celtic cross and is located near the northern path of the north section in the original cemetery.

Butcher’s many publications include, in collaboration with Andrew Lang, a prose translation of Homer‘s Odyssey which appears in 1879 and the OCT edition of Demosthenes, Orationes, vol. I (Or. 1-19, Oxford, 1903), II.i (Or. 20–26, Oxford, 1907).

Members of

Members of