Daniel Murray, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, dies in Dublin on February 26, 1852.

Murray is born on April 18, 1768, at Sheepwalk, near Arklow, County Wicklow, the son of Thomas and Judith Murray, who are farmers. At the age of eight he goes to Thomas Betagh‘s school at Saul’s Court, near Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. At sixteen, Archbishop John Carpenter sends him to the Irish College at Salamanca, completing his studies at the University of Salamanca. He is ordained priest in 1792 at the age of twenty-four.

After some years as curate at St. Paul’s Church, Dublin, Murray is transferred to Arklow, and is there in 1798 when the rebellion breaks out. The yeomanry shoots the parish priest in bed and Murray, to escape a similar fate, flees to the city where for two years he serves as curate at St. Andrew’s Chapel on Hawkins Street. As a preacher, he is said to be particularly effective, especially in appeals for charitable causes, such as the schools. He is then assigned to the Chapel of St. Mary in Upper Liffey Street where Archbishop John Troy is the parish priest.

In 1809, at the request of Archbishop Troy, Murray is appointed coadjutor bishop, and consecrated on November 30, 1809. In 1811 he is made Administrator of St. Andrew’s. That same year he helps Mary Aikenhead establish the Religious Sisters of Charity. While coadjutor he fills for one year the position of president of St. Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

Murray is an uncompromising opponent of a proposal granting the British government a “veto” over Catholic ecclesiastical appointments in Ireland, and in 1814 and 1815, makes two separate trips to Rome concerning the controversy.

Murray becomes Archbishop of Dublin in 1825 and on November 14, 1825 celebrates the completion of St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral. He enjoys the confidence of successive popes and is held in high respect by the British government. His life is mainly devoted to ecclesiastical affairs, the establishment and organisation of religious associations for the education and relief of the poor. With the outbreak of cholera in the 1830s, in 1834 he and Mother Aikenhead found St. Vincent’s Hospital. He persuades Edmund Rice to send members of the Christian Brothers to Dublin to start a school for boys. The first is opened in a lumber yard on the city-quay. He assists Catherine McAuley in founding the Sisters of Mercy, and in 1831 professes the first three members.

Edward Bouverie Pusey has an interview with Murray in 1841, and bears testimony to his moderation, and John Henry Newman has some correspondence with him prior to Newman’s conversion from the Anglican Church to the Roman Catholic Church in 1845. A seat in the privy council at Dublin, officially offered to him in 1846, is not accepted. He takes part in the synod of the Roman Catholic clergy at Thurles in 1850.

Towards the end of his life, Murray’s eyesight is impaired, and he reads and writes with difficulty. Among his last priestly functions is a funeral service for Richard Lalor Sheil who had died in Italy, and whose body had been brought back to Ireland for burial. Murray dies in Dublin on February 26, 1852, at the age of eighty-four. He is interred in the St. Mary’s Pro-Cathedral, Dublin, where a marble statue of him has been erected in connection with a monument to his memory, executed by James Farrell, president of the Royal Hibernian Academy of Fine Arts.

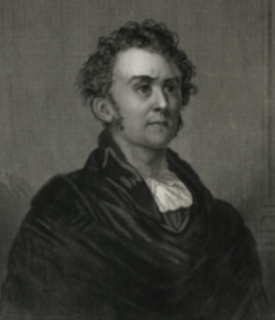

(Pictured: Portrait of Daniel Murray, Archbishop of Dublin, by unknown 19th century Irish portrait painter)