The Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, receives royal assent on April 13, 1829. The act removes the sacramental tests that bar Roman Catholics in the United Kingdom from Parliament and from higher offices of the judiciary and state. It is the culmination of a fifty-year process of Catholic emancipation which had offered Catholics successive measures of “relief” from the civil and political disabilities imposed by Penal Laws in both Great Britain and in Ireland in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

Convinced that the measure is essential to maintain order in Catholic-majority Ireland, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, helps overcome the opposition of King George IV and of the House of Lords by threatening to step aside as Prime Minister and retire his Tory government in favour of a new, likely-reform-minded Whig ministry.

In Ireland, the Protestant Ascendancy has the assurance of the simultaneous passage of the Parliamentary Elections (Ireland) Act 1829. Its substitution of the British ten-pound for the Irish forty-shilling freehold qualification disenfranchises over 80% of Ireland’s electorate. This includes a majority of the tenant farmers who had helped force the issue of emancipation in 1828 by electing to parliament the leader of the Catholic Association, Daniel O’Connell.

O’Connell had rejected a suggestion from “friends of emancipation,” and from the English Roman Catholic bishop, John Milner, that the fear of Catholic advancement might be allayed if the Crown were accorded the same right exercised by continental monarchs: a veto on the confirmation of Catholic bishops. O’Connell insists that Irish Catholics would rather “remain forever without emancipation” than allow the government “to interfere” with the appointment of their senior clergy. Instead, he relies on their confidence in the independence of the priesthood from Ascendancy landowners and magistrates to build his Catholic Association into a mass political movement. On the basis of a “Catholic rent” of a penny a month (typically paid through the local priest), the Association mobilises not only the Catholic middle class, but also poorer tenant farmers and tradesmen. Their investment enables O’Connell to mount “monster” rallies that stay the hands of authorities, and embolden larger enfranchised tenants to vote for pro-emancipation candidates in defiance of their landlords.

O’Connell’s campaign reaches its climax when he himself stands for parliament. In July 1828, he defeats a nominee for a position in the British cabinet, William Vesey-FitzGerald, in a County Clare by-election, 2057 votes to 982. This makes a direct issue of the parliamentary Oath of Supremacy by which, as a Catholic, he will be denied his seat in the Commons.

As Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Wellington’s brother, Richard Wellesley, had attempted to placate Catholic opinion, notably by dismissal of the long-serving Attorney-General for Ireland, William Saurin, whose rigid Ascendancy views and policy made him bitterly unpopular, and by applying a policy of prohibitions and coercion against not only the Catholic Ribbonmen but also the Protestant Orangemen. But now both Wellington and his Home Secretary, Robert Peel, are convinced that unless concessions are made, a confrontation is inevitable. Peel concludes, “though emancipation was a great danger, civil strife was a greater danger.” Fearing insurrection in Ireland, he drafts the Relief Bill and guides it through the House of Commons. To overcome the vehement opposition of both the King and of the House of Lords, Wellington threatens to resign, potentially opening the way for a new Whig majority with designs not only for Catholic emancipation but also for parliamentary reform. The King initially accepts Wellington’s resignation and the King’s brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, attempts to put together a government united against Catholic emancipation. Though such a government would have considerable support in the House of Lords, it would have little support in the Commons and Ernest abandons his attempt. The King recalls Wellington. The bill passes the Lords and becomes law.

The key, defining, provision of the Acts is its repeal of “certain oaths and certain declarations, commonly called the declarations against transubstantiation and the invocation of saints and the sacrifice of the mass, as practised in the Church of Rome,” which had been required “as qualifications for sitting and voting in parliament and for the enjoyment of certain offices, franchises, and civil rights.” For the Oath of Supremacy, the act substitutes a pledge to bear “true allegiance” to the King, to recognise the Hanoverian succession, to reject any claim to “temporal or civil jurisdiction” within the United Kingdom by “the Pope of Rome” or “any other foreign prince … or potentate,” and to “abjure any intention to subvert the present [Anglican] church establishment.”

This last abjuration in the new Oath of Allegiance is underscored by a provision forbidding the assumption by the Roman Church of episcopal titles, derived from “any city, town or place,” already used by the United Church of England and Ireland. (With other sectarian impositions of the Act, such as restrictions on admittance to Catholic religious orders and on Catholic-church processions, this is repealed with the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1926.)

The one major security required to pass the Act is the Parliamentary Elections (Ireland) Act 1829. Receiving its royal assent on the same day as the relief bill, the act disenfranchises Ireland’s forty-shilling freeholders, by raising the property threshold for the county vote to the British ten-pound standard. As a result, “emancipation” is accompanied by a more than five-fold decrease in the Irish electorate, from 216,000 voters to just 37,000. That the majority of the tenant farmers who had voted for O’Connell in the Clare by-election are disenfranchised as a result of his apparent victory at Westminster is not made immediately apparent, as O’Connell is permitted in July 1829 to stand unopposed for the Clare seat that his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy had denied him the year before.

In 1985, J. C. D. Clark depicts England before 1828 as a nation in which the vast majority of the people still believed in the divine right of kings, and the legitimacy of a hereditary nobility, and in the rights and privileges of the Anglican Church. In Clark’s interpretation, the system remained virtually intact until it suddenly collapsed in 1828, because Catholic emancipation undermined its central symbolic prop, the Anglican supremacy. He argues that the consequences were enormous: “The shattering of a whole social order. … What was lost at that point … was not merely a constitutional arrangement, but the intellectual ascendancy of a worldview, the cultural hegemony of the old elite.”

Clark’s interpretation has been widely debated in the scholarly literature, and almost every historian who has examined the issue has highlighted the substantial amount of continuity before and after the period of 1828 through 1832.

Eric J. Evans in 1996 emphasises that the political importance of emancipation was that it split the anti-reformers beyond repair and diminished their ability to block future reform laws, especially the great Reform Act of 1832. Paradoxically, Wellington’s success in forcing through emancipation led many Ultra-Tories to demand reform of Parliament after seeing that the votes of the rotten boroughs had given the government its majority. Thus, it was an ultra-Tory, George Spencer-Churchill, Marquess of Blandford, who in February 1830 introduced the first major reform bill, calling for the transfer of rotten borough seats to the counties and large towns, the disfranchisement of non-resident voters, the preventing of Crown officeholders from sitting in Parliament, the payment of a salary to MPs, and the general franchise for men who owned property. The ultras believed that a widely based electorate could be relied upon to rally around anti-Catholicism.

In Ireland, emancipation is generally regarded as having come too late to influence the Catholic-majority view of the union. After a delay of thirty years, an opportunity to integrate Catholics through their re-emerging propertied and professional classes as a minority within the United Kingdom may have passed. In 1830, O’Connell invites Protestants to join in a campaign to repeal the Act of Union and restore the Kingdom of Ireland under the Constitution of 1782. At the same, the terms under which he is able to secure the final measure of relief may have weakened his repeal campaign.

George Ensor, a leading Protestant member of the Catholic Association in Ulster, protests that while “relief” bought at the price of “casting” forty-shilling freeholders, both Catholic and Protestant, “into the abyss,” might allow a few Catholic barristers to attain a higher grade in their profession, and a few Catholic gentlemen to be returned to Parliament, the “indifference” demonstrated to parliamentary reform will prove “disastrous” for the country.

Seeking, perhaps, to rationalise the sacrifice of his freeholders, O’Connell writes privately in March 1829 that the new ten-pound franchise might actually “give more power to Catholics by concentrating it in more reliable and less democratically dangerous hands.” The Young Irelander John Mitchel believes that the intent is to detach propertied Catholics from the increasingly agitated rural masses.

In a pattern that had been intensifying from the 1820s as landlords clear land to meet the growing livestock demand from England, tenants have been banding together to oppose evictions and to attack tithe and process servers.

One civil disability not removed by 1829 Act are the sacramental tests required for professorships, fellowships, studentships and other lay offices at universities. These are abolished for the English universities – Oxford, Cambridge and Durham – by the Universities Tests Act 1871, and for Trinity College Dublin by the “Fawcett’s Act” 1873.

Section 18 of the 1829 act, “No Roman Catholic to advise the Crown in the appointment to offices in the established church,” remains in force in England, Wales and Scotland, but is repealed with respect to Northern Ireland by the Statute Law Revision (Northern Ireland) Act 1980. The entire act is repealed in the Republic of Ireland by the Statute Law Revision Act 1983.

On the night of Saturday, October 7, 1843, a proclamation is issued from

On the night of Saturday, October 7, 1843, a proclamation is issued from

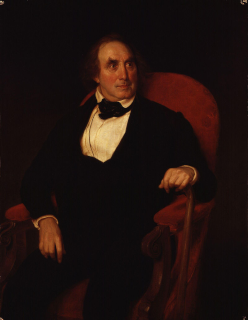

Robert Peel (pictured), chief secretary of Ireland (1812-18), establishes the Peace Preservation Force to counter rural unrest on July 25, 1814. This rudimentary paramilitary police force is designed to provide policing in rural Ireland, replacing the 18th century system of watchmen, baronial constables, revenue officers, and British military forces.

Robert Peel (pictured), chief secretary of Ireland (1812-18), establishes the Peace Preservation Force to counter rural unrest on July 25, 1814. This rudimentary paramilitary police force is designed to provide policing in rural Ireland, replacing the 18th century system of watchmen, baronial constables, revenue officers, and British military forces.