Albert George Morrow, Irish illustrator, poster designer and cartoonist, dies at his home in West Sussex, England, on October 26, 1927.

Morrow is born on April 26, 1863, in Comber, County Down, the second son of George Morrow, a painter and decorator from Clifton Street in west Belfast. Of his seven brothers, four, George, Jack, Edwin, and Norman, are also illustrators and all but one are artists. He is a keen ornithologist in his youth. In later life he is a keen walker and paints landscapes for leisure.

Morrow is educated at the Belfast Model School and latterly at the Belfast Government School of Art between 1878 and 1881.

While studying under T. M. Lindsay at the Government School of Art in 1880, Morrow is awarded a £10 prize for drawing from the eminent publishers Cassell, Petter and Galpin. In 1881, while still learning his trade, he paints a mural of Belfast for the Working Men’s Institute in Rosemary Street, where his father is chairman. Later in that same year he exhibits a watercolour sketch of a standing figure entitled Meditative at the gallery of Rodman & Company, Belfast.

Morrow then wins a three-year scholarship worth £52 per year which he takes to the National Art Training School at South Kensington in 1882, where he begins a lifelong friendship with the British sculptor Albert Toft. In 1883, while still attending South Kensington, he joins the staff of The English Illustrated Magazine in preparation for the launch of the first edition. Two of his works are published in the Sunday at Home magazine in September of the same year.

J. Comyns Carr, first editor of The English Illustrated Magazine, commissions Morrow to complete a series on English industry when he has yet to complete his studies at South Kensington.

In 1890, Morrow begins illustrating for Bits and Good Words. He exhibits nine works at the Royal Academy of Arts between 1890 and 1904, all of which are watercolours, and another in 1917, and an offering in chalk at the 159th Exhibition, in the year of his death.

Morrow becomes a member of the Belfast Art Society in 1895, exhibiting with them in the same year. In 1896, a Morrow print is published in Volume 2 of the limited-edition print-collection Les Maîtres de l’Affiche selected by “Father of the Poster” Jules Chéret. In the same year he shows a watercolour of a Gurkha at the Earls Court in the Empire of India and Ceylon exhibition. In 1900, he exhibits with two Ulster artists, Hugh Thomson and Arthur David McCormick, at the Linen Hall Library in Belfast, who along with Morrow had contributed to the early success of The English Illustrated Magazine.

Morrow is one of the founders of the Ulster Arts Club in November 1902 along with five of his brothers, an organisation that has a nonsectarian interest in Celtic ideas, language and aesthetics. In November 1903, he exhibits at the first annual exhibition of the Club when he shows alongside John Lavery, Hans Iten, James Stoupe and F. W. Hull. He exhibits The Itinerant Musician, a watercolour that he had previously shown at the Royal Academy in 1902. Honorary membership is conferred upon him the following year. Three years later he is honoured with a solo exhibition of sketches and posters in conjunction with the Ulster Arts Club, at the Belfast Municipal Gallery.

In 1908, Morrow joins his brothers in an exhibition at 15 D’Olier Street, Dublin, an address which is later registered to the family business in 1913. Among his contributions to the family exhibition is his painting of Brandon Thomas, The Clarionette Player, which had previously been exhibited at the Royal Academy, and a poster entitled Irving in Dante.

In 1917, Morrow joins his brother George and 150 artists and writers, in petitioning the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to find a way of enacting the unsigned codicil to Hugh Lane’s will and establish a gallery to house Lane’s art collection in Dublin. Among the 32 notable artists who sign this petition are Jack B. Yeats, Sir William Orpen, Sir John Lavery, and Augustus John.

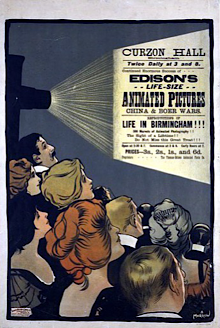

Morrow illustrates books for children and adults, but he is best known for the hundreds of posters he designs for the theatre, with the bulk of his commissions coming from just one lithographical printer, David Allen and Sons. As a cartoonist he draws for children’s annuals, and contributes three cartoons to Punch in 1923, 1925 and posthumously in 1931.

Morrow dies at his home in West Hoathly, West Sussex, on October 26, 1927, at the age of 64. He is survived by his wife and two children. His headstone in the local churchyard at All Saints Church, Highbrook is designed by his friend, the sculptor and architect, Albert Toft.

Morrow’s works can be found in many public and private collections such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, Musée des Arts Décoratifs and the British Museum.

(Pictured: Colour lithograph poster by Albert Morrow advertising a cinematic showing at the Curzon Hall, Birmingham, c. 1902)