On January 11, 1970, at Sinn Féin‘s Ard Fheis at the Intercontinental Hotel in Ballsbridge, Dublin, the proposal to end abstentionism and take seats, if elected, in the Dáil, the Northern Ireland Parliament, and the Parliament of the United Kingdom is put before the members. A similar motion had been adopted at an Irish Republican Army (IRA) convention the previous month, leading to the formation of a Provisional Army Council by Seán Mac Stíofáin and other members opposed to the leadership.

There are allegations of malpractice and that some supporters cast votes to which they are not entitled. In addition, the leadership has also refused voting rights to a number of Sinn Féin cumainn (branches) known to be in opposition, particularly in the north and in County Kerry. The motion is debated all of the second day, and when it was put to a vote at 5:30 PM the result is 153:104 in favour of the motion, failing to achieve the necessary two-thirds majority.

The Executive attempts to circumvent this by introducing a motion in support of the IRA Army Council, led by Tomás Mac Giolla, which only requires a simple majority. In protest of the motion, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and his minority group walks out of the meeting. These members reconvene at a hall in 44 Parnell Square, which they had already booked in anticipation of the move by the leadership. They appoint a Caretaker Executive, and pledged allegiance to the Provisional Army Council.

The Caretaker Executive declares itself in opposition to the ending of abstentionism, the drift towards Marxism, the failure of the leadership to defend the nationalist people of Belfast during the 1969 Northern Ireland riots, and the expulsion of traditional republicans by the leadership during the 1960s. At the October 1970 Ard Fheis, it is announced that an IRA convention has been held and has regularised its structure, bringing the “provisional” period to an end.

At the end of 1970 the terms “Official IRA” and “Regular IRA” are introduced by the press to differentiate the two factions. During 1971, the rival factions play out their conflict in the press with the Officials referring to their rivals as the Provisional Alliance, while the Provisionals refer to the Officials (IRA and Sinn Féin) as the National Liberation Front (NLF).

The Falls Road Curfew, coupled with internment in August 1971, and Bloody Sunday in Derry in January 1972, boosts the Provisionals in Belfast. These events produce an influx into the Provisionals on the military side, making them the dominant force and finally eclipsing the Officials everywhere. Despite becoming the dominant group and the dropping of the word “provisional” at the convention of the IRA Army Council in September 1970, they are still known to the mild irritation of senior members as Provisionals, Provos, or Provies.

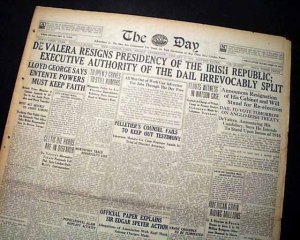

The Anglo-Irish Treaty is introduced to replace the Republic with a dominion of the British Commonwealth with the King represented by a Governor-General of the Irish Free State. The Treaty is finally signed on December 6, 1921.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty is introduced to replace the Republic with a dominion of the British Commonwealth with the King represented by a Governor-General of the Irish Free State. The Treaty is finally signed on December 6, 1921.

The Night of the Big Wind (Irish: Oíche na Gaoithe Móire), a powerful European windstorm sweeps without warning across Ireland beginning in the afternoon of January 6, 1839, causing severe damage to property and several hundred deaths. As many as one quarter of the houses in north Dublin are damaged or destroyed and 42 ships are wrecked. The storm tracks eastward to the north of Ireland bringing winds gusts of over 100 knots to the south before moving across the north of England and onto the European continent where it eventually dies out. At the time, it is the most damaging Irish storm in 300 years.

The Night of the Big Wind (Irish: Oíche na Gaoithe Móire), a powerful European windstorm sweeps without warning across Ireland beginning in the afternoon of January 6, 1839, causing severe damage to property and several hundred deaths. As many as one quarter of the houses in north Dublin are damaged or destroyed and 42 ships are wrecked. The storm tracks eastward to the north of Ireland bringing winds gusts of over 100 knots to the south before moving across the north of England and onto the European continent where it eventually dies out. At the time, it is the most damaging Irish storm in 300 years.

Daniel “Dan” Keating is born in Castlemaine, County Kerry, on January 2, 1902. Keating is a life-long Irish republican and patron of Republican Sinn Féin.

Daniel “Dan” Keating is born in Castlemaine, County Kerry, on January 2, 1902. Keating is a life-long Irish republican and patron of Republican Sinn Féin.