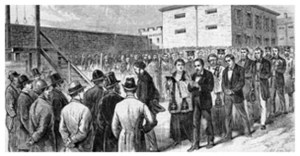

John “Black Jack” Kehoe, the last of the Molly Maguires, is hanged in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, on December 18, 1878.

The Molly Maguires is an Irish secret society that is allegedly responsible for some incidents of vigilante justice in the coalfields of eastern Pennsylvania. They defend their actions as attempts to protect exploited Irish American workers. They are, in fact, often regarded as one of the first organized labor groups.

In the first five years of the Great Famine in Ireland that begins in 1845, 500,000 immigrants come to the United States from Ireland — nearly half of all immigrants to the United States during these years. The tough economic circumstances facing the immigrants lead many Irish men to the anthracite fields in the mountains of eastern Pennsylvania. Miners work under dangerous conditions and are severely underpaid. Small towns owned by the mining companies further exploit workers by charging rent for company housing. In response to these abuses, secret societies like the Molly Maguires spring up, leading sporadic terrorist campaigns to settle worker/owner disputes.

Members of the Molly Maguires are accused of murder, arson, kidnapping, and other crimes. Industry owners become increasingly concerned about the threat posed by the Molly Maguires. Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, hires the Pinkerton Detective Agency to infiltrate the secret society and find evidence that can be used against them. James McParland, who later becomes the most celebrated private detective of the era, takes the high-risk assignment and goes undercover within the organization. For more than two years, he establishes his place in the Molly Maguires and builds trust among his fellow members.

Eventually, several Molly Maguires confess their roles in a murder to McParland. When he is finally pulled out of the society in February 1876, his information leads to the arrest and conviction of nineteen men.

In June 1877, ten Molly Maguires are hanged on a single day in what becomes known as “Pennsylvania’s Day of the Rope.” In December of the following year, Kehoe is arrested and hanged for the 1862 murder of Frank W. S. Langdon, a mine foreman, despite the fact that it is widely believed he is wrongly accused and not actually responsible for anyone’s death. Although the governor of Pennsylvania, John F. Hartranft, believes Kehoe’s innocence, he signs the death warrant anyway. Kehoe’s hanging at the gallows is officially hailed as “the Death of Molly-ism.”

Though the deaths of the vigilante Molly Maguires help quell the activity of the secret society, the increased assimilation of the Irish into mainstream society and their upward mobility out of the coal jobs is the real reason that protective secret societies like the Molly Maguires eventually fade into obscurity.

In 1979, Pennsylvania Governor Milton Shapp grants a posthumous pardon to Kehoe after an investigation by the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons. The request for a pardon is made by one of Kehoe’s descendants. Kehoe proclaims his innocence until his death. The Board recommends the pardon after investigating Kehoe’s trial and the circumstances surrounding it. Shapp praises Kehoe, saying the men called “Molly Maguires” are “martyrs to labour” and heroes in the struggle to establish a union and fair treatment for workers.