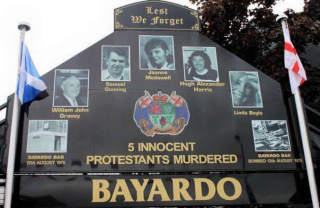

The Kingsmill massacre, also referred to as the Whitecross massacre, is a mass shooting that takes place on January 5, 1976, near the village of Whitecross in south County Armagh, Northern Ireland. Gunmen stop a minibus carrying eleven Protestant workmen, line them up alongside it and shoot them. Only one victim survives, despite having been shot 18 times. A Catholic man on the minibus is allowed to go free. A group calling itself the South Armagh Republican Action Force claims responsibility. It says the shooting is retaliation for a string of attacks on Catholic civilians in the area by Loyalists, particularly the killing of six Catholics the night before. The Kingsmill massacre is the climax of a string of tit for tat killings in the area during the mid-1970s, and is one of the deadliest mass shootings of the Troubles.

On January 5, 1976, just after 5:30 p.m., a red Ford Transit minibus is carrying sixteen textile workers home from their workplace in Glenanne. Five are Catholics and eleven are Protestants. Four of the Catholics get out at Whitecross and the bus continues along the rural road to Bessbrook. As the bus clears the rise of a hill, it is stopped by a man in combat uniform standing on the road and flashing a torch. The workers assume they are being stopped and searched by the British Army. As the bus stops, eleven gunmen in combat uniform and with blackened faces emerge from the hedges. A man “with a pronounced English accent” begins talking. He orders the workers to get out of the bus and to line up facing it with their hands on the roof. He then asks, “Who is the Catholic?” The only Catholic is Richard Hughes. His workmates, now fearing that the gunmen are loyalists who have come to kill him, try to stop him from identifying himself. However, when Hughes steps forward the gunman tell him to “get down the road and don’t look back.”

The lead gunman then says, “Right,” and the others immediately open fire on the workers. The eleven men are shot at very close range with automatic rifles, which includes Armalites, an M1 carbine and an M1 Garand. A total of 136 rounds are fired in less than a minute. The men are shot at waist height and fall to the ground, some falling on top of each other, either dead or wounded. When the initial burst of gunfire stops, the gunmen reload their weapons. The order is given to “Finish them off,” and another burst of gunfire is fired into the heaped bodies of the workmen. One of the gunmen also walks among the dying men and shoots them each in the head with a pistol as they lay on the ground. Ten of them die at the scene: John Bryans (46), Robert Chambers (19), Reginald Chapman (25), Walter Chapman (23), Robert Freeburn (50), Joseph Lemmon (46), John McConville (20), James McWhirter (58), Robert Walker (46) and Kenneth Worton (24). Alan Black (32) is the only one who survives. He had been shot eighteen times and one of the bullets had grazed his head. He says, “I didn’t even flinch because I knew if I moved there would be another one.”

After carrying out the shooting, the gunmen calmly walk away. Shortly after, a married couple comes upon the scene of the killings and begin praying beside the victims. They find the badly wounded Alan Black lying in a ditch. When an ambulance arrives, Black is taken to a hospital in Newry, where he is operated on and survives. The Catholic worker, Richard Hughes, manages to stop a car and is driven to Bessbrook Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) station, where he raises the alarm. One of the first police officers on the scene is Billy McCaughey, who had taken part in the Reavey killings. He says, “When we arrived it was utter carnage. Men were lying two or three together. Blood was flowing, mixed with water from the rain.” Some of the Reavey family also come upon the scene of the Kingsmill massacre while driving to hospital to collect the bodies of their relatives. Johnston Chapman, the uncle of victims Reginald and Walter Chapman, says the dead workmen were “just lying there like dogs, blood everywhere”. At least two of the victims are so badly mutilated by gunfire that immediate relatives are prevented from identifying them. One relative says the hospital mortuary “was like a butcher’s shop with bodies lying on the floor like slabs of meat.”

Nine of the dead are from the village of Bessbrook, while the bus driver, Robert Walker, is from Mountnorris. Four of the men are members of the Orange Order and two are former members of the security forces: Kenneth Worton is a former Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) soldier while Joseph Lemmon is a former Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) officer. Alan Black is appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 2021 New Year Honours, for his cross-community work since the massacre.

The next day, a telephone caller claims responsibility for the attack on behalf of the “South Armagh Republican Action Force” or “South Armagh Reaction Force.” He says that it was retaliation for the Reavey–O’Dowd killings the night before, and that there will be “no further action on our part” if loyalists stop their attacks. He adds that the group has no connection with the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The IRA denies responsibility for the killings as it is on a ceasefire at the time.

However, a 2011 report by the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) concludes that Provisional IRA members were responsible and that the event was planned before the Reavey and O’Dowd killings which had taken place the previous day, and that “South Armagh Republican Action Force” was a cover name. Responding to the report, Sinn Féin spokesman Mitchel McLaughlin says that he does “not dispute the sectarian nature of the killings” but continues to believe “the denials by the IRA that they were involved”. Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) Assemblyman Dominic Bradley calls on Sinn Féin to “publicly accept that the HET’s forensic evidence on the firearms used puts Provisional responsibility beyond question” and to stop “deny[ing] that the Provisional IRA was in the business of organising sectarian killings on a large scale.”

The massacre is condemned by the British and Irish governments, the main political parties and Catholic and Protestant church leaders. Merlyn Rees, the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, condemns the massacre and forecasts that the violence will escalate, saying “This is the way it will go on unless someone in their right senses stops it, it will go on.”

The British government immediately declares County Armagh a “Special Emergency Area” and deploys hundreds of extra troops and police in the area. A battalion of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) is called out and the Spearhead Battalion is sent into the area. Two days after the massacre, the British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announces that the Special Air Service (SAS) is being sent into South Armagh. This is the first time that SAS operations in Northern Ireland are officially acknowledged. It is believed that some SAS personnel had already been in Northern Ireland for a few years. Units and personnel under SAS control are alleged to be involved in loyalist attacks.

The Kingsmill massacre is the last in the series of sectarian killings in South Armagh during the mid-1970s. According to Willie Frazer of Families Acting for Innocent Relatives (FAIR), this is a result of a deal between the local UVF and IRA groups.

(Pictured: The minibus carrying the textile factory workers is left peppered with bullet holes and blood stains the ground after the massacre, as detectives patrol the scene of the murders)