On June 15, 2010, David Cameron, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, issues a formal state apology for the “unjustified and unjustifiable” killing of fourteen civil rights marchers in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland by British soldiers on Bloody Sunday, January 30, 1972. Cameron says Lord Saville inquiry’s long-awaited report shows soldiers lied about their involvement in the killings and that all of those who died were innocent.

Bloody Sunday, as the events on January 30, 1972, come to be known, is one of the most controversial moments of the Troubles. Paramilitary open fire while trying to police a banned civil rights march. They kill 13 marchers outright, and, according to Saville, wound another 15, one of whom subsequently dies later in the hospital.

In the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, Cameron begins his statement by saying he is “deeply patriotic” and does not want to believe anything bad about his country. Cameron says the inquiry, a 5,000-page, 10-volume report, which takes twelve years to compile at a cost of almost £191m, is “absolutely clear” and there are “no ambiguities” about the conclusions. He adds, “What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong.”

The report concludes there is no justification for shooting at any of those killed or wounded on the march. “None of the firing by the Support Company [Paratroopers] was aimed at people posing a threat or causing death or serious injury.” The report adds that the shootings “were not the result of any plan to shoot selected ringleaders” and that none of those killed by British soldiers was armed with firearms and no warning was given by the soldiers.

“The government is ultimately responsible for the conduct of the armed forces, and for that, on behalf of the government and on behalf of the country, I am deeply sorry,” says Cameron. The inquiry finds that the order sending British soldiers into the Bogside “should not have been given.” Cameron adds the casualties were caused by the soldiers “losing their self-control.”

The eagerly awaited report does not hold the British government at the time directly responsible for the atrocity. It finds that there is “no evidence” that either the British government or the unionist-dominated Northern Ireland administration encouraged the use of lethal force against the demonstrators. It also exonerates the army’s then commander of land forces, Major General Robert Ford, of any blame.

Most of the damning criticism against the military is directed at the soldiers on the ground who fired on the civilians. Saville says that on Bloody Sunday there had been “a serious and widespread loss of fire discipline among the soldiers.” He concludes that many of the soldiers lied to his inquiry. “Many of these soldiers have knowingly put forward false accounts in order to seek to justify their firing.” Under the rules of the inquiry this conclusion means that soldiers could be prosecuted for perjury.

The report also focuses on the actions of two Republican gunmen on the day and says that the Official Irish Republican Army (IRA) men had gone to a prearranged sniping position. But Saville finds that their actions did not provoke in any way the shootings by the paramilitary regiment.

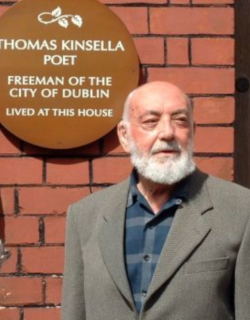

Relatives cheer as they watch the statement, relayed to screens outside the Guildhall in Derry. A minute of silence is held as thousands of supporters fill the square outside, waiting to be told about the report’s contents. A representative of each of the families speaks in turn and a copy of the hated report by Lord Widgery, which in 1972 accuses the victims of firing weapons or handling bombs, is torn apart by one of the families’ representatives.

Denis Bradley, who played a key part in secret talks that brought about the IRA ceasefire of 1994 and who was on the Bloody Sunday march in 1972, welcomes the report’s findings. The former Derry priest, who narrowly escaped being shot on the day, says he is “amazed” at how damning the findings are against the soldiers. He adds, “This city has been vindicated, this city has been telling the truth all along.”

(Pictured: Family and supporters watch David Cameron’s formal state apology in Guildhall Square in Derry, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland)