Myles Byrne, United Irishman, French army officer, and author, dies at his house in the rue Montaigne (now rue Jean Mermoz, 8th arrondissement, near Champs-Élysées), Paris on January 24, 1862.

Byrne is born on March 20, 1780, at Ballylusk, Monaseed, County Wexford, the eldest son of Patrick Byrne, a middling Catholic farmer, and Mary (née Graham). He joins the United Irishmen in the spring of 1797 and, although only seventeen, becomes one of the organisation’s most active agents in north Wexford.

When rebellion engulfs his home district on May 27, 1798, Byrne assumes command of the local Monaseed corps and rallies them at Fr. John Murphy‘s camp on Carrigrew Hill on June 3. They fight at the rebel victory at Tubberneering on June 4 and the unsuccessful attempt to capture Arklow five days later. After the dispersal of the main rebel camp at Vinegar Hill on June 21, he accompanies Murphy to Kilkenny but begins the retreat to Wexford four days later. Heavily attacked at Scollagh Gap, he is one of a minority of survivors who spurn the proffered amnesty and join the rebel forces in the Wicklow Mountains. He is absent when the main force defeats a cavalry column at Ballyellis on June 30 but protects the wounded who are left in Glenmalure when the rebels launch a foray into the midlands the following week. He takes charge of the Wexfordmen who regain the mountains and fight a series of minor actions in the autumn and winter of 1798 under the militant Wicklow leader Joseph Holt. On November 10, he seizes an opportunity to escape into Dublin, where he works as a timber-yard clerk with his half-brother Edward Kennedy.

Byrne is introduced to Robert Emmet in late 1802 and immediately becomes a prominent figure in his insurrection plot. He is intended to command the many Wexford residents of the city during the planned rising of 1803. On July 23, 1803, he assembles a body of rebels at the city quays, which disperse once news is received that the rising has miscarried. At Emmet’s request, he escapes to Bordeaux in August 1803 and makes his way to Paris to inform Thomas Addis Emmet and William James MacNeven of the failed insurrection. In his Paris diary, the older Emmet recalls passing on “the news brought by the messenger” to Napoleon Bonaparte‘s military advisors.

Byrne enlists in the newly formed Irish Legion in December 1803 as a sub-lieutenant and is promoted to lieutenant in 1804 but only sees garrison duty. The regiment eventually moves to the Low Countries, and is renamed the 3rd Foreign Regiment in 1808, the year he is promoted to captain. He campaigns in Spain until 1812, participating in counterinsurgency against Spanish guerillas. He fights in Napoleon’s last battles and is appointed Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur on June 18, 1813. With Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the former Irish Legion, with its undistinguished and somewhat unfortunate history, is disbanded.

Though a supporter of Napoleon during the Hundred Days, Byrne is not involved in his return, yet he is included in an exclusion order from France which he successfully appeals. In November 1816, he swears the oath of loyalty to the now Royal Order of the Legion of Honour and becomes a naturalised French subject by royal decree on August 20, 1817. He becomes a half-pay captain but is recalled for active service in 1828 and serves as a staff officer in the French expeditionary force in Morea in support of Greek independence (1828–1830). His conduct on this campaign leads to his promotion as chef de bataillon (lieutenant-colonel) of the 56th Infantry Regiment in 1830.

After five years of service in garrisons around France, including counterinsurgency duty in Brittany, Byrne retires from the army in 1835. On December 24, 1835, he marries a Scottish woman, Frances “Fanny” Horner, at the British Embassy Chapel in Paris. They live in modest circumstances in various parts of Paris and remain childless. Though it is unclear when he is awarded the Chevalier de St Louis, having initially applied for it unsuccessfully in 1821, this distinction is mentioned in his tomb inscription, under his Legion of Honour. John Mitchel, who visits him regularly in Paris in the late 1850s, recalls Byrne sporting the rosette of the Médaille de Sainte Hélène, awarded in 1857 to surviving veterans of Napoleon’s campaigns.

An early list of Irish Legion officers describes Byrne as an upright and disciplined man, with little formal instruction but aspiring to improve himself. He becomes fully fluent in French but also learns Spanish and his language skills are a useful asset in various campaigns. Because of his suspected Bonapartist leanings, he is under police surveillance for some time after the Bourbon Restoration. He does, however, cultivate a wide social circle in Paris over the years. Various references throughout his writings testify to an inquisitive and cultured mind. He intended publishing a lengthy criticism of Gustave de Beaumont‘s Irlande, sociale, politique et religieuse (1840), claiming that it misrepresented the 1798 rebellion, but he withdraws it after meeting the author, not wishing to prejudice the reception of such an important French work on “the sufferings of Ireland.”

A lifelong nationalist, Byrne acts as Paris correspondent of The Nation in the 1840s and is a well-known figure in the Irish community there. He works in the 1850s on his notably unapologetic and candid Memoirs, an early and significant contribution to the Irish literature of exile. This autobiography is acclaimed by nationalists when published posthumously by his wife in 1863, with a French translation swiftly following in 1864. His detailed testimony of key battles of the 1798 rebellion in the southeast and Emmet’s conspiracy are written with the immediacy of an eyewitness and make them an invaluable contribution to that period of Irish history.

Byrne dies on January 24, 1862, in Paris, and is buried in Montmartre Cemetery. On November 25, 1865, John Martin writes of him: “In truth he was a beautiful example of those natures that never grow old. A finer, nobler, gentler, kindlier, gayer, sunnier nature never was than his, and to the last he had the brightness and quickness and cheeriness of youth”.

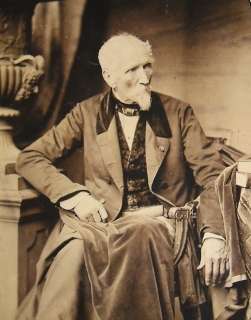

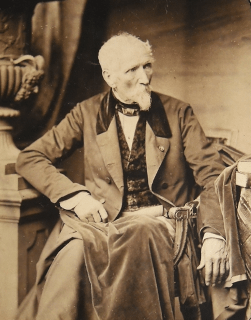

Byrne’s engaging and dispassionate Memoirs have ensured his special status among Irish nationalists. Because of his longevity he is the only United Irishman to have been photographed. His wife had sketched him in profile in middle age, and the photograph taken almost three decades later shows the same, strong features though those of a frail, but dignified man of 79 years.

(From: “Byrne, Miles” by Ruan O’Donnell and Sylvie Kleinman, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009, last revised August 2024 | Pictured: Photograph of Miles Byrne taken in Paris in 1859)