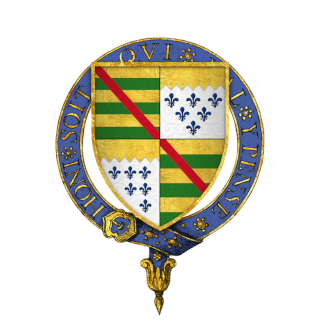

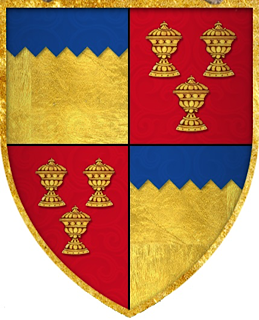

Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond, 1st Earl of Ossory, also known as Red Piers, dies on August 26, 1539. He is from the Polestown branch of the Butler family of Ireland. In the succession crisis at the death of Thomas Butler, 7th Earl of Ormond, he succeeds to the earldom as heir male, but loses the title in 1528 to Thomas Boleyn. He regains it after Boleyn’s death in 1538.

Butler is born c. 1467, the third son of James Butler and Sabh Kavanagh. His father is Lord Deputy of Ireland, Lord of the Manor of Advowson of Callan (1438–87). His father’s family is the Polestown cadet branch of the Butler dynasty that started with Sir Richard Butler of Polestown, second son of James Butler, 3rd Earl of Ormond. His mother, whose first name is variously given as Sabh, Sadhbh, Saiv, or Sabina, is a princess of Leinster, eldest daughter of Donal Reagh Kavanagh, MacMurrough (1396–1476), King of Leinster.

In 1485, Butler marries Lady Margaret FitzGerald, daughter of Gerald FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare and Alison FitzEustace. The marriage is political, arranged with the purpose of healing the breach between the two families. In the early years of their marriage, Margaret and her husband are reduced to penury by James Dubh Butler, a nephew, heir to the earldom and agent of the absentee Thomas Butler, 7th Earl of Ormond, who resides in England. Butler retaliates by murdering James Dubh in an ambush in 1497. He is pardoned for his crime on February 22, 1498.

Butler and Margaret have three sons: James (1496–1546), also called “the Lame,” who succeeds him as the 9th Earl, Richard (1500–1571), who becomes the 1st Viscount Mountgarret, and Thomas, who is slain by Dermoid Mac Shane, MacGillaPatrick of Upper Ossory, and six daughters: Margaret, Catherine (1506–53), Joan (born 1528), married James Butler, 10th Baron Dunboyne, Ellice (1481–1530), Eleanor, married Thomas Butler, 1st Baron Cahir, and Helen, also called Ellen (1523–97), married Donough O’Brien, 2nd Earl of Thomond.

Butler also has an illegitimate son, Edmund Butler, who becomes Archbishop of Cashel and conforms to the established religion in 1539.

During the prolonged absence from Ireland of the earls, Butler’s father lays claim to the Ormond land and titles. This precipitates a crisis in the Ormond succession when the seventh earl later dies without a male heir. On March 20, 1489, King Henry VII appoints him High Sheriff of County Kilkenny. He is knighted before September 1497. The following year (1498) he seizes Kilkenny Castle and with his wife, the dynamic daughter of the Earl of Kildare, likely improve the living accommodations there. On February 28, 1498, he receives a pardon for crimes committed in Ireland, including the murder of James Ormonde, heir to the 7th Earl. He is also made Seneschal of the Liberty of Tipperary on June 21, 1505, succeeding his distant relation, James Butler, 9th Baron Dunboyne.

Henry VII is succeeded by Henry VIII in 1509. On the death of Thomas Butler, 7th Earl of Ormonde on August 3, 1515, Butler becomes the 8th Earl of Ormond.

In March 1522, Henry VIII appoints him Chief Governor of Ireland as Lord Deputy. He holds this office until August 1524 when he is succeeded by Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare. However, he holds on to the position of Lord Treasurer.

One of the heirs general to the Ormond inheritance is Thomas Boleyn, whose mother is Lady Margaret Butler, second daughter of the 7th Earl. Thomas Boleyn is the father of Anne, whose star is rising at the court of King Henry VIII. As the king wants the titles of Ormond and Wiltshire for Thomas Boleyn, he induces Butler and his coheirs to resign their claims on February 17, 1528. Aided by the king’s Chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Butler is created Earl of Ossory instead. On February 22, 1538, the earldom of Ormond is restored to him.

Butler dies on August 26, 1539, and is buried in St. Canice’s Cathedral, Kilkenny.