Sir Robert Prescott Stewart, organist, conductor, composer, teacher, and academic, dies in Dublin on March 24, 1894. He is one of the most influential (classical) musicians in 19th-century Ireland.

Stewart is born on December 16, 1825, the second of two sons of Charles Frederick Stewart of 6 Pitt Street (now Balfe Street), Dublin, librarian of King’s Inns. Nothing is known of his mother other than that she studies music with one of the Logier family, presumably the noted military musician and piano teacher Johann Bernhard Logier, a resident of Dublin from 1809.

Stewart is educated at Christ Church Cathedral school in Dublin, where he is a chorister. He begins to accompany choral services in his early teens, and in 1844 is appointed organist of Christ Church Cathedral and the Trinity College Dublin (TCD) chapel. In addition, in 1852 he becomes de facto organist of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and holds all three positions concurrently for the rest of his life.

Stewart’s first conducting appointment is with the Dublin University Choral Society in 1846, to which he later adds similar appointments in Dublin, Bray, and Belfast. He is active as a teacher, both privately and from 1869 at the Royal Irish Academy of Music (RIAM), and as a critic with the Dublin Daily Express. On occupying the University of Dublin‘s chair of music in 1862, he takes steps to formalise requirements for the music baccalaureate, introducing examinations in a modern language, Latin (or a second modern language), English (literature and composition), arithmetic, and music history. As a result, though not until 1878, similar examinations are introduced at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge. In his professorial capacity he delivers in the 1870s public lectures on Bach, Handel, Wagner, church music, music education, organology, and, most notably, Irish music, in which he reveals an uncanny knowledge of the wire-strung harp and the uilleann pipes. He also contributes entries on Irish music and musicians to the first edition of George Grove‘s A Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

By all accounts, Stewart is a very adept musician, having perfect pitch, a formidable memory, and astonishing facility in transposition. Apparently an autodidact, he is the first Irish organist to cultivate pedal technique, while in the art of improvisation both Joseph Robinson and Sir John Stainer hold him to be the equal of Mendelssohn.

Intent on broadening his musical horizons, Stewart travels widely. From 1851 he is a regular visitor to London, and from 1857 makes frequent trips to Continental Europe, attending the Beethoven and Schumann festivals at Bonn in 1871 and 1873 respectively and Wagner’s first Bayreuth Festival in 1876. On the initiative of the Dublin University Choral Society, he is conferred with the simultaneous degrees of Mus.B. and Mus.D. at a special ceremony on April 9, 1851. On February 28, 1872, he is knighted at Dublin Castle by John Poyntz Spencer, 5th Earl Spencer, a social climb that Stewart, who has no independent income, can afford only by accumulating professional appointments and by relentless private teaching. In addition to successive townhouses in the vicinity of Merrion Square, he owns a smaller property on Bray Esplanade, named Holyrood.

Among Stewart’s compositions, his disciple James Culwick lists about forty part songs (of which several win prizes), more than twenty solo songs, fifteen anthems, several church services, a quantity of shorter liturgical music, and sixteen choral cantatas with orchestra. Three of the cantatas set texts by John Francis Waller: the 24-movement A Winter Night’s Wake (1858), The Eve of St. John (1860) and Inauguration Ode for the Opening of the National Exhibition of Cork (1852) for the opening of the Irish Industrial Exhibition in Cork. Other occasional pieces are Who Shall Raise the Bell? (The Belfry Cantata) for the inauguration of Trinity College campanile in 1854, Ode to Shakespeare (1870) for the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival, Orchestral Fantasia (1872) for the Boston Peace Festival, How Shall We Close Our Gates? (1873) for the Dublin Exhibition and Tercentenary Ode (1892) for the tercentenary of Trinity College Dublin.

Though Stewart destroys many of his works, his surviving music is consistently well crafted, and the rapid decline in the popularity of the odes is at least partly attributable to the tawdry and ephemeral character of their texts. Yet despite his esteem for Wagner, he never shakes off the conservative stylistic influences of Handel, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn, and the posthumous performance of his music has been restricted almost entirely to the Dublin cathedrals.

In August 1846 Stewart marries Mary Emily Browne, the daughter of Peter Browne of Rahins House, Castlebar, County Mayo. They have four daughters, of whom the eldest dies in 1858. Following Mary’s death on August 7, 1887, he marries on August 9, 1888, Marie Wheeler of Hyde, Isle of Wight, the daughter of Joseph Wheeler of Westlands, Queenstown (now Cobh).

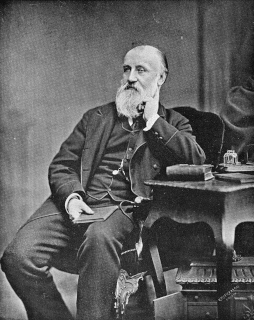

Stewart dies in Dublin on March 24, 1894, and is buried at Mount Jerome Cemetery alongside his first wife and eldest daughter. Portraits of him are in the possession of the Dublin University Choral Society and the Royal Irish Academy of Music (RIAM), and his statue, erected on Leinster Lawn in 1898, still stands.

(From: “Stewart, Sir Robert Prescott” by Andrew Johnstone, Dictionary of Irish Biography, http://www.dib.ie, October 2009)