Brian Dillon, Irish republican leader and a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), dies at his home in Cork, County Cork, on August 17, 1872. He is a central figure in the Cork Fenian movement.

Dillon is born in Glanmire, County Cork, in 1830. As a child, he is injured in a heavy fall which results in curvature of the spine and general ill health. His family moves to a house near the corner of Old Youghal Road and Ballyhooly Road. He attends the School of Art for several years and becomes quite talented with brush and pencil. He lives through the Great Famine and becomes an ardent nationalist.

Dillon is appointed a Fenian leader in Cork by James Stephens, the head of the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Under his supervision the Fenian recruits drill on the Fair Field and at Rathpeacon and are hoping for a rebellion in 1865 when the Fenians are at their strongest. He often associates with other Cork Fenians such as John J. Geary, James Mountaine and John Lynch. He chairs the Fenian meetings at Geary’s pub.

In September 1865, police arrest Fenian leaders James Stephens and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Dublin, and Dillon in Cork. The police search his home and find a pair of field glasses, some drawings and some incriminating letters sewn into the mattress of his bed. He is remanded in Cork City Gaol until his trial.

On December 18, Dillon and another Cork Fenian, John Lynch, are tried together in the dock in Cork Courthouse by Judge Keogh. The charges are primarily based on information provided by an informer named John Warner, an ex-military pensioner. Isaac Butt and Mr. Waters represent the defendants. The charges are “in one indictment with having conspired to depose the Queen, &c., and with illegally drilling and being drilled in furtherance of that design.” Both are found guilty, based primarily on the testimony of informants, although John Warner’s account is very weak and unsatisfactory under cross-examination. The defendants are sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude.

Dillon is brought under armed guard by train from Cork to Dublin and then thrown into Mountjoy Gaol. He spends nearly a month there and suffers from lack of sleep. In January 1866, he and John Sarsfield Casey are handcuffed together on the tough and rough sea crossing between Kingstown and Holyhead. On arrival at Holyhead, they are then taken by train to Pentonville Prison. This is a very cold prison, and he becomes seriously ill in May 1866. He is transferred to the hospital wing of Woking Convict Invalid Prison, and this is to be his home for the next four-and-a-half years. Here he becomes Convict Number 2658.

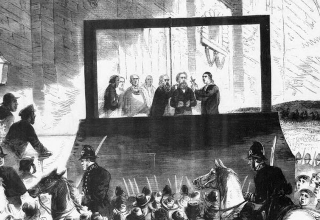

In 1870, after five years imprisonment, a commission is set up to investigate the Fenian prisoners, and on account of his bad health, this commission recommends that Dillon be allowed home to Cork. In January 1871 he is transferred to Millbank Prison London and is set free two weeks later on February 8. The following day he arrives in Dublin and after a few days’ rest, he returns to Cork by train. All along the route thousands of people wait on the platforms to greet him and read special addresses of welcome. The train reaches Cork at 8:00 p.m. and even though a carriage and pair are waiting, he is glad to seek refuge in the first covered car he can find, so dense is the crowd all around him wanting to shake his hand. The triumphal procession from the station to his home then begins and the hills all along the route are lighted with tar barrels.

Amid emotional scenes Dillon meets his family and afterwards appears at one of the windows of the house and thanks the people of Ireland for the great reception he has received everywhere on his journey home to Cork. He is now in very poor health and his mother begins the task of nursing him back to health. Everything that loving care and money could do is done, and from New York comes a cheque for £50 from the generous-hearted O’Donovan Rossa. Other friends also contribute, but all to no avail. On Saturday, August 17, 1872, he dies at his home surrounded by his sorrowing relatives.

Dillon’s funeral is one of the biggest ever seen in Cork. The cortege is headed by the Barrack Street Band, and at least ten other bands take part. All have their instruments dressed in sombre black. On Monday, August 18, his remains are privately borne to St. Joseph’s cemetery, to a temporary resting place, as it has been decided to build a vault in the family burial ground in Rathcooney which will not be ready for a few days. Later the funeral route travels from Turners Cross along Anglesea Street, South Mall, Grand Parade, Patrick Street, McCurtain Street and St. Luke’s. The funeral procession stops outside his home and prayers are recited for the repose of his soul. The procession then moves on toward Ballyvolane and up the steep hill toward the graveyard at Rathcooney. On arrival at the newly built tomb, so dense is the crowd milling around the hearse that considerable difficulty is experienced in getting the coffin to the grave. The priests then read the burial service, and, in a hushed silence, Canon Freeman asks the entire assembly to kneel and recite the Lord’s Prayer aloud. He blesses the grave, and the mortal remains of Brian Dillon are lowered to rest. The coffin is then covered, and after Colonel Ricard O’Sullivan Burke‘s oration, the crowd quietly disperses.

Today Dillon’s name is inscribed in the National Monument on the Grand Parade and in street names like Dillon’s Cross, Brian Dillon Park and Brian Dillon Crescent. The Brian Dillons GAA club in the same area of Cork city is also named after him.

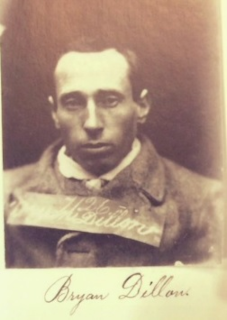

(Pictured: A mug shot of Brian Dillon)